Matt O’Leary transformed the use of lesson observations in FE, despite sector leaders who were initially reluctant to listen. And he’s far from finished, as Jess Staufenberg discovers

There are few academics who can point to a seismic change in Ofsted’s approach to further education and say “I did that”, but Matt O’Leary, despite his modesty, is probably as close as it gets.

The professor of education at Birmingham City University, whose roots are as an ESOL teacher and teacher trainer in FE colleges, did his PhD on lesson observations during his mid-30s and hasn’t looked back since. Just two years later in 2013, he produced a report for the University and College Union with the unassuming title “Developing a National Framework for the Effective Use of Lesson Observation in Further Education”. By 2014, a senior Ofsted bod was tweeting: “Ofsted is to pilot FE and skills inspections without grading teaching in individual sessions” and by 2015, graded lesson observations had been scrapped altogether.

O’Leary is unpresuming about the impact of his research in achieving this outcome, and even more cautious about how much the official policy change has translated into practice within colleges. He comes across as a remarkably even-handed person, with a sharp, even playful, eye for detail. “One thing to remember is there was a lot of political brokering going on at that point. While I like to think my research influenced their policy direction, I’m not that naïve that I don’t also realise there were a lot of spats going on and Ofsted partly needed to ingratiate themselves to the profession.”

There was a lot of political brokering, a lot of spats going on

Yet in all the news stories it was O’Leary’s research that was cited as prompting the change. To those who hailed the removal of graded lesson observations as a “great victory”, he has also warned “repeatedly, that we’re still in a position where the vast majority of colleges adopt a performance management approach to observation that categorises lecturers in some way.” He adds: “There is progress, but this is a slower burner”.

Like his professional life, O’Leary has a rather extraordinary backstory which, despite some quite trying circumstances, he describes with a light touch. He was born in Birmingham to Irish parents and his three older sisters in a three-bedroomed house. The girls had one bedroom, his parents the other and he had the box room. As the only boy, he was “banished” from intruding on his sisters’ space and spent his primary years “obsessed with football” and “getting in trouble a lot” with his headmistress, who in 1970s Birmingham appears to have been handy with a slipper.

The city also had a darker side: as an Irish family in England during the Troubles, they were often targets of discrimination. “I remember one particular summer was the first time I saw my mother cry. We went through a week of having the milk bottles on the doorstep destroyed. I also remember people referring to me as ‘Paddy’ and thinking, ‘why are they saying that to me?’”

It was among the dialects of the Black Country, where O’Leary attended secondary school, that he developed an ear for languages. He recalls a French class going through declensions of être. “We got onto ‘nous sommes’ and the teacher, who was from Surrey, asks if anyone knows what it means. The boy next to me says ‘wim, Miss’. She says, ‘sorry?’ and he says ‘wim!’ and she’s completely confused. He gets really frustrated and says ‘we am, Miss!’” O’Leary chuckles happily down the phone.

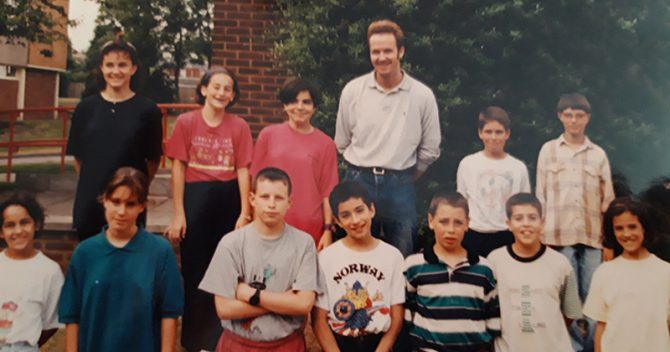

Curiosity must be a driving facet of O’Leary’s character, because he headed off to Southampton University to study Spanish and French, despite not only his parents never attending higher education – his father was a lorry driver and his mother worked part-time in a newsagents – but none of his sisters either. A stint abroad in Mexico as a language assistant for his degree led him to gain a PGCE from Birmingham City University and head back for four years to teach English as a foreign language in the Mexican city of Toluca. O’Leary, who had been boxing since his teens, relates with delight bumping into Mexican multi-time world champion Julio César Chávez. In fact, he seems a master of telling a good tale out of the interesting moments he’s encountered – a master of observation, you might say.

Perhaps my favourite story comes from his first job back in London in 1996, where he had a role teaching a post-16 English access course to Greek and Cypriot students. O’Leary relates the day he took the cohort to an exam hall. “Within five minutes, the invigilator came out looking furious, saying ‘your students are a disgrace – they’re copying!’. I went in to talk to them and they were completely taken aback, saying ‘what’s the big deal, we’re sharing with each other?’” O’Leary hoots with laughter. “It was completely culturally different for them. We just didn’t realise.”

Most colleges still adopt a performance management approach to observation

It seems an abiding interest in how humans understand each other makes O’Leary tick. Both as head of department for ESOL at a further education college near London, and later as a teacher trainer at City College Coventry, he revelled in classes filled with multiple cultures and viewpoints. “From a teaching perspective, it’s like a dream, really. When you set up activities for them you’ve got a head start, because they have a natural curiosity to find out about each other’s lives.” O’Leary taught and trained teachers to educate everyone from refugees and asylum seekers, au pairs, retired headteachers and vicars. Among the melee, he noticed the anxiety among lecturers about graded lesson observations (both internal or for Ofsted inspections). It was soon to become his life’s work.

The practice has a long history. Under the Further Education Funding Council’s inspectorate, an unloved 1 to 7 grading system for lesson observations was in force, with similar guises continued by the Adult Learning Inspectorate and then Ofsted – often so the inspectorate could check the college’s own self-assessment system, as well as the supposed quality of teaching. By the time O’Leary began his UCU research in 2012, his surveys unleashed a tide of frustration. About 1,600 respondents wrote more than 100,000 words in the comment box. “The answers ranged from several words to three to four pages. I had to take a moment and step back!” says O’Leary. “I thought, the fact they’ve responded with such volume means this is something the sector feels really strongly about.” His report concluded that the views of participants were “divided” between lecturers who criticised the “counterproductive consequences” and senior managers who praised the benefits. O’Leary recommended the sector find “alternative approaches to the use of observation”, which “prioritised improvements in teaching”, and which “severed the link” between observations and capability procedures.

There is progress, but this is a slower burner

The divide O’Leary noticed among his respondents was soon replicated in the reception of his report. Writing in FE Week, former inspector Phil Hatton blasted the report for interviewing more lecturers than college leaders, and said: “If you cannot put on a performance without notice, there has to be something very lacking in your ability.” Meanwhile O’Leary recalls first presenting his results to the AoC’s annual conference for senior leaders in Birmingham. “There was this stony silence. I could almost literally see people looking daggers at me,” he tells me, chuckling again. “I realised afterwards they weren’t ready to hear it.” For the remaining detractors today, O’Leary puts it this way: “Your average main grade lecturer on a full-time contract teaches 830 hours a year. Under the traditional observation model, they might be observed for one of those 830 hours. Then quite an absolutist judgment is made, which could stop you getting a salary increment or put you in disciplinary proceedings.”

Not someone who strikes you as a deliberate provocateur, O’Leary is currently developing a middle-way compromise, which he terms “unseen observation”. With its roots in counseling practices, it involves a coach and lecturer meeting up to discuss the latter’s aims and activities for a lesson, and then again afterwards to discuss what went well or badly. “The very fact of removing the act of observation makes an incredible difference,” says O’Leary. “It forces people to reflect really deeply on their practice.” O’Leary confirms a highly skilled ‘unobserver’ is a crucial ingredient.

O’Leary seems to present a powerful lesson: be always interested in the perspectives and experiences of others. It will make you a better observer.

Your thoughts