FE Week meets a principal whose small and perfectly formed college provides a fitting platform from which to launch a big recovery

The miracle college turnaround. The supersized provider. The super-principal. The disruptor who transformed the system. We’re all guilty of fetishising the big and bold stories. You won’t find that here.

Instead, you’ll find a reminder of the value of longevity, of putting down roots and committing to a community. In fact, if there’s a lesson to be learned from Nav Chohan and his principalship of Shipley College, we might as well break all the conventions and get to it from the start. It is that in this age of globalised economy and global pandemic, the little guy has the advantage.

The little guy here is Shipley College, “probably one of the smallest FE colleges in the country”, says its principal. “Quite often when I’m at principals’ parties, they’re quite surprised about how small we are.” Shipley has just 2,725 learners on roll. Chohan, however, has a big personality, just the kind of person you’d trust to liven up a party. His next comment is a humorous dig at his big-college peers: “People often talk about economies of scale, but they don’t talk about ‘diseconomies of scale’, which is on the second page.”

There’s more than a gentle ribbing of other principals here. “Economies of scale is a manufacturing term,” he says. “It doesn’t really apply to the service sector. So at Shipley we stay firm to our roots, and we have an incredible staff. Have you ever been there?”

I won’t call Shipley outstanding because we’re never perfect

In times past I’d be in Saltaire to interview him. Instead, when we speak by video conference, I have to confess that I haven’t. His clear enthusiasm for the place makes me regret it. “It’s just north of Bradford and it’s a World Heritage site. It’s the most beautiful college site in the country probably, an absolutely gorgeous place to be.”

I’m sold. To speak of the zeal of the convert would be an over-statement, but London-born Chohan clearly loves where he finds himself. His career began as a maths teacher in a Nottingham comprehensive 32 years ago. He has since taught computing at West London and Hammersmith College, and before his move to Shipley he gave 12 years to Leeds City College, finishing there as its director of further and higher education.

There are few principals who stay 11 years in one college. (“They usually leave before their mistakes come out,” Chohan quips.) He has been chair of the West Yorkshire Consortium of Colleges (WYCC) and Leeds City Region Skills network (LCRSN) since 2019 – a group whose influence and policy work he typically downplays to focus on their value as colleagues and critical friends (“They’ve let me do the job because I’ve been in post longest.”) Under his leadership, Shipley has been a “rock-solid good” college in Ofsted’s book since 2013.

In didn’t start that way. Just over a year into his tenure, in October 2010, Ofsted downgraded the college to ‘satisfactory’. His statement that “it was a hard thing to get out of” typifies someone who is his own harshest critic. Indeed that Ofsted report mentioned his recent arrival, his already effective agenda for change and the college’s honest self-appraisal. Had Shipley been inspected 18 months earlier, the story may have been of a transformative turnaround with Chohan as its hero in 2013 when the college was once again rated good.

Since then, Shipley has received two further grade 2s from the inspectorate. “I suppose one regret would be that we haven’t got to outstanding. But that might be a reflection of the way we manage the place. I think we’re worth celebrating, but maybe there’s just a little too much humility. I don’t want to call it outstanding because we’re never perfect.”

Principals usually leave before their mistakes come out

Chohan is full of praise for the colleges that have secured the elusive rating, but he isn’t the type to dwell on a judgment by someone else’s standards. Even that early ‘satisfactory’ report, far from a terrible failure, gives a clear indication of his vision for Shipley and his priorities in leadership. It deemed the college “good for employer-responsive provision”, and praised its inclusive curriculum and provision for employers, “strong partnerships with a wide range of groups that lead to benefits for all parties,” and support for vulnerable learners.

Ten years on and a decade of government austerity, economic uncertainty following Brexit and a global pandemic may just show the wisdom of setting those priorities as Shipley College’s foundations. “Having a solid FE college, even in the common difficulties the sector is facing, to be fairly confident about the future, that’s not a bad place to be.”

Like everyone else, Chohan is concerned about the Covid-19 shutdown’s impact on his students’ industry placements. Yet his focus isn’t so much on qualifications, which he has faith can be sorted. His worry is for something greater that his students will have lost: “The most important thing – maybe even more important than the education bit – is having that placement, being in adult situations. It brings them along and develops them so much.”

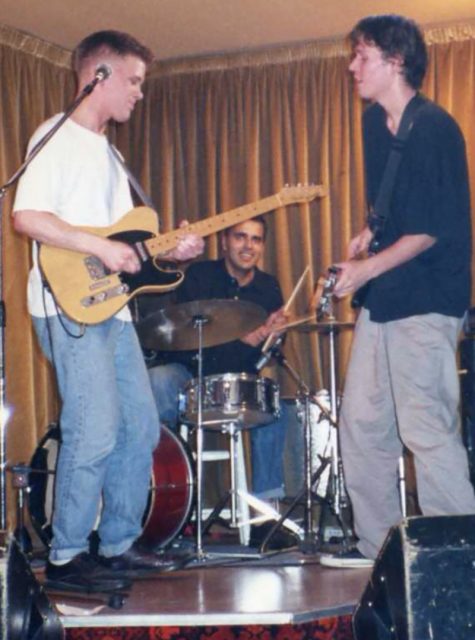

Placing value on the real experience over the paper evidence evidently runs deep with the Shipley principal. It applies to his assessment of the college as much as to his assessment of his learners’ needs, and it can be traced throughout his career. When he graduated from the University of Bath, he pursued glory as a drummer over a predictable career platform. The rest, as they say, is history.

“I had no talent and this probably wasn’t the direction for me, so towards the end of my year on the dole I got a place on a community programme. That community programme had me working at a city farm in Bristol. I started to teach kids in the local area some basic IT stuff and that’s probably what got me into teaching.”

Later, he took a four-year break from teaching to go in search of industry experience, ostensibly to become a better teacher. It took him back to London, and then to Edinburgh where he worked his way up from systems analyst to project manager for the NHS. A return to teaching was always on the cards, however.

It’s only days later, in a sort of postscript to our interview, that I learn from Chohan that his mother, Bikram, was a junior school teacher. She and his father, Nirmal, were first-generation Sikh immigrants from India who lived and raised him in Greenford, west London, “which has all the hassles of living in London, but none of the glamour”.

They had high aspirations – dad became a civil servant and mum a teacher – and for their son. “There is absolutely no way on Earth I wasn’t going to university. That was presumed from minus nine months.” He took five years to complete his degree in electrical engineering. “My key lesson from university was I wasn’t quite as bright as I thought I was,” he says with a wry smile.

And yet, despite that harsh self-assessment, Chohan occupies a place from which he can affect policy in West Yorkshire and beyond. As I write this piece, chancellor Rishi Sunak is set to announce a “Plan for Jobs” with a major focus on young people, and Chohan’s closing statement of our interview springs to mind: “We do need some kind of solution for people who have unfortunately been made unemployed, and making that happen is going to be a partnership among all the institutions of West Yorkshire, private, and public. Because people deserve that chance.”

With a devolution deal announced for the region just days before lockdown, the influence of local organisations such as the WYCC and LCRSN is only likely to grow, with little Shipley College at its heart.

It’s not a big, brash story, but it does go to show that taking staying lean, flexible and honest can really pay off.

What a breath of fresh air! As you point out at the start of the piece, a welcome change from the all too familiar ‘it’s all about my brilliant leadership’/’rise like a rocket, fall like a stick’ scenario.

Spot-on. Outstanding and genuine leadership!