The Manchester College principal, Lisa O’Loughlin explains her collaborative strategy to provide the city with routes out of deprivation. By JL Dutaut

When Manchester mayor, Andy Burnham called this week for schools to be closed to create a “true circuit break”, it is safe to assume that, as with so many other politicians’ educational announcements, the “and colleges” bit was intended, if silent.

That’s a shame at any time, but given the impact of the virus in Manchester and the north west, and the work colleges like The Manchester College, part of LTE Group, have done for their students and communities, it is a doubly frustrating omission. Since the initial lockdown, Manchester has suffered a lengthy period of restrictions higher than the rest of the nation, and as the prime minister beat a reluctant path to a second lockdown, the region’s plight became totemic for the inequalities the pandemic has brought to light and sharpened across the nation.

There is a multiplier effect going on in northern towns at the moment

When I interviewed The Manchester College’s principal, Lisa O’loughlin just days before the second lockdown was announced, her comments already foreshadowed Burnham’s fears, expressed this week, for what could happen if Manchester came out on 2 December and straight back into a regional tier 3. “We’re concerned that it isn’t a level playing field. And yet, at the end of this academic year, our learners will be assessed in the same way as the students in a tier one or tier two area.”

And it isn’t just about the academic impact. “What COVID does is it places a set of pressures on communities,” she adds. “Overlaid on other fundamental aspects of deprivation, that is creating a situation which is more challenging for our learners. We have students from very, very deprived communities. We have a high proportion of learners without GCSE English or maths. There is a multiplier effect going on in northern towns at the moment.”

But if anyone understands the nefarious effects of that regional deprivation and how to go about tackling them, it is surely O’Loughlin. A northerner through and through, she’s been at the college since 2013, its principal since 2014, and spent the previous ten years of her career at Blackburn College. She went to school in Wigan, graduated from Manchester University and got her teaching qualification from the University of Central Lancashire.

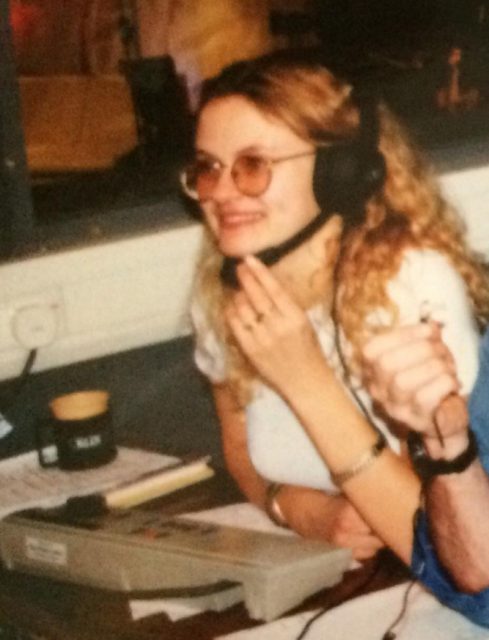

And O’loughlin is not unfamiliar with the barriers she is dedicated to helping students overcome. From a modest background, her father a joiner, her mother a seamstress and her two older sisters a secretary and a nurse, she was “very lovingly referred to as the odd one in the family”. She attended local catholic schools and was lucky enough to be academically able – though it did mean she was encouraged to park her artistic interests to pursue academic subjects. She was the first to go to university, where she studied media and business management, and later came back to the arts for a master’s degree. Today, a principal and mother – she has little time for it herself but, married to artist, Jamie, her life is still steeped in it.

After a decade spent in media production, O’loughlin was asked to cover a class at a local college, and was hooked. She gained her teaching qualification and moved to Blackburn College, which had TV production facilities. “It allowed me to keep a foot in both camps,” she says, but she’s never looked back since.

People described The Manchester College as a soft landing place for our community

A local success story then, principalship hasn’t all been plain sailing for O’loughlin. Rated ‘good’ by Ofsted in May 2014 – just 6 months before she took the top spot from Jack Carney, who had recruited her as vice principal – The Manchester College’s climb from its previous ‘satisfactory’ rating wasn’t to be sustained. By 2017, the college was back in category 3, deemed to require improvement in every area except apprenticeships, where it was judged to be ‘inadequate’. “When I joined in 2013,” O’Loughlin tells me, “people described it as a soft landing place for our community, and that’s a really lovely way of describing the college, but we lacked the ambition we needed for our learners.” But the 2017 Ofsted visit didn’t account for a strategy the college had already put in place a year before, that hadn’t yet borne fruit. “Accelerating progress, ambitions towards careers, and positive advocacy. Those are the key underpinnings of our strategy for social mobility.”

That social mobility strategy came with the formation of LTE Group, to which The Manchester College is central, accounting for some 25,000 of its purported 95,000 learners across the country. LTE Group isn’t the result of horizontal integration through college mergers – though The Manchester College is itself the result of a long line of mergers over decades – but rather across a much broader field of education and training. The first such partnership of its kind according to its own literature, today it comprises corporate professional development provider MOL, offender education, training and employability provider Novus, apprenticeships provider Total People, and degree-level course provider UCEN. As well as the college of course, albeit with a re-purposed offer.

The group’s shared expertise paid off. By 2019, it was rated ‘good’ in every area. The previously ‘inadequate’ apprenticeships provision, now managed by Total People, was no longer in Ofsted’s scope for inspection – though it was rated ‘good’ in its own inspection. Achieving that meant taking a long hard look at local provision and zeroing in on the college’s place in it. “We have some excellent sixth form colleges in Manchester, and some of the highest performing in the country. And so what we asked was, ‘what is it that we should be providing for our communities?’ and it’s very much a route to a technical or professional career. We are The Manchester College. There isn’t another big GFEC in Manchester so if anybody’s going to do it, it’s got to be us.”

Just last week, former skills and apprenticeships minister, Anne Milton welcomed the publication of the College of the Future Commission’s final review. Of its 11 recommendations, she particularly highlighted the ineffectiveness and cost of competition and joined calls for greater local collaboration. Based on her LTE experience, O’loughlin, who is also chair of the Greater Manchester Colleges Group since 2016, has some very clear ideas about that.

Accelerating progress and positive advocacy – those are our key underpinnings

For a start, notwithstanding any white papers and plans to take colleges back into public ownership, balancing collaboration and competition is something she evidently feels Westminster could learn something about from the regions. “Manchester is fantastic at collaborating to improve outcomes. We’ve been doing a lot of that work for about four or five years, developing that kind of strategic perspective on how skills should develop across the city region, and we’ve become a really strong strategic senior partner to the combined authority and to the local authorities. That’s a real positive and I suppose, ahead of the white paper, is a bit of a model for a way of working.”

As everywhere else, Covid has “intensified” that partnership working. Monthly meetings of the group of nine colleges are now more likely to be weekly or fortnightly and bilateral conversations a normal part of life. But balancing that collaboration with a healthy amount of competition – the type that is purported to create the conditions for improvement – is a recipe no policy maker has yet cracked. Again, O’loughlin has ideas. She’s clear that even in Manchester, there is a constant risk that competition will gain the upper hand. “We manage to collaborate in spite of it,” she says.

The key, she suggests, is not in regulating competition or enforcing contrived collaboration, but in accepting that curriculum itself determines where specialisation is required. “Up to level three, we believe that all colleges should offer a broad-based provision, because that’s what our communities need. But at level four or five, there is an opportunity for us to each become specialists. Obviously, capital investments and so on are better invested and better value for money if you’re not spreading it across a number of organisations. For us, we feel that that is something that absolutely we could achieve.”

Collaboration, then, not as a vehicle for improvement through partnership working, but as a means of ensuring investment is targeted to ensure all learners across a region have access to the best possible training and facilities for their sector. A simple redefinition of terms, it’s an approach that is already unlocking a wealth of opportunities for the learners of Greater Manchester and could do so for other regions.

After all, it was the facilities at Blackburn that gave O’loughlin her first step to where she is now, advocating for Manchester’s students. So as the skills sector faces the continued impact of Covid and the end of the Brexit transition phase in the coming months, here’s hoping her words penetrate the Westminster bubble.

Your thoughts