Skills England chair Phil Smith is a former GB triathlete with boundless amounts of energy. Which is good; he will need it.

The day before I met this straight-talking Scotsman near his village home in Warwickshire, the 67 year old had cycled 75 miles with a group of 20-somethings.

His ‘part-time’ Skills England role is meant to take up two or three days a month, leaving time for his numerous other roles: chair of the Digital Skills Council, a board member for the National Theatre and the University of Coventry, and non-executive chairman of fintech companies Appyway and Streeva.

But the Skills England role is so far taking up “four or five days a week”. He has 300 meetings queued up and could “literally fill my diary up to 12 hours a day, every day”.

“I want to be responsive to people. But I also recognise there’s just an amount you can do,” he says.

Labour’s new flagship skills body has been the subject of months of debate in parliament, with his role specifically lauded by ministers as providing independence once IfATE is officially abolished on June 1.

Contrary to a report from the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) stating it was “not yet clear why any employer, provider or strategic authority would pick up the phone” to Skills England, Smith says no one has been avoiding his calls.

“Probably 100 per cent” of those he is speaking to have been “really enthusiastic and supportive” of Skills England.

But how long will the honeymoon period last?

Much responsibility sits on his shoulders to appease the sometimes conflicting interests in the skills system that span industry, education and training, unions and local and regional government.

He finds it “slightly overwhelming” that at “pretty much every meeting and dinner” he attends, the feedback is: “So you’re going to fix it then, are you? We’ve been waiting for Skills England to come along”.

Perhaps he acts as a therapeutic outlet for those who are frustrated with the current system, I suggest. “Exactly, it’s kind of a shoulder to cry on,” he replies. “But there is a genuine desire to get the system fixed.”

Real power

Some naysayers see Skills England as weak because it was formed as an executive agency that sits within the Department for Education.

Any notion I might have had that Smith could speak openly to me without government interference was swept away before our interview; after we agreed on a date, the DfE press office waded in and postponed it until after the bill absorbing Skills England’s predecessor body, the Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education (IfATE), into DfE received royal assent. Now, at the interview, Smith is accompanied by a Skills England press officer.

He says he is “slightly neutral” to the argument that Skills England lacks sufficient independence or strength. He has “not specifically” pushed for more powers and points out that he also sits on the industrial strategy advisory council.

“As far as I can see, I’ve got all the mandate I want to recommend or change the skills system. I have not had any resistance in that from right up to secretary of state, or even prime minister level.

“It’s too easy to overthink problems before you even get started.”

Leader and coach

Smith is a corporate heavyweight who spent 22 years as chief executive of tech firm Cisco, and six chairing the UK’s innovation agency, Innovate UK. He was officially appointed in February to give Skills England “strong credibility with employers”, as skills minister Jacqui Smith put it.

The rest of his leadership team are public sector stalwarts; joint chief executives Tessa Griffiths and Sarah Maclean were previously job-sharing directors for DfE’s post-16 skills and strategy, and deputy Gemma Marsh was Greater Manchester’s director of education, work and skills (with a two-year secondment to Downing Street). Smith’s vice chair, Sir David Bell – also a Scotsman – was a DfE permanent secretary.

Smith sees part of his role as a leader and coach who can help his colleagues “fit into those roles”.

He is also “really pleased” that the rest of his board, with whom he had an introductory call this week, incorporate “different voices” from the FE, HE, regional government and business sectors.

He rebuts allegations I put to him that Skills England is just another bureaucratic talking shop; it has “real people doing real jobs”, including performing all of IfATE’s former functions and DfE’s skills research arm the Unit for Future Skills. He highlights the “brilliant work” of its Skills Compass project, in which a large language model is being trained on job descriptions and adverts to look at “trends of how future technologies affect the skills you have to teach people at different levels”.

But Smith is himself more of a visionary than a stickler for technical details.

He is “not sure” he wants to get “bogged down in all the technicalities of some things in the skills system” and adds: “There’s plenty of people in Skills England who are expert on these areas.”

Can-do attitude

Smith began his career as a computer programmer for Phillips, spending six years there then nine at IBM before joining Cisco. The US giant’s UK office back then only employed about 10 people. By the time he left 23 years later it had become one of the UK’s biggest tech employers. Smith is particularly proud of the positive work culture he instilled there.

The year before he stepped down, an employee engagement survey found 100 per cent of its staff were “proud or very proud” to work there.

“Cisco is a company that sold boxes that go in cupboards, yet people wanted to change the world.” He wants to enthuse Skills England with a similar can-do attitude.

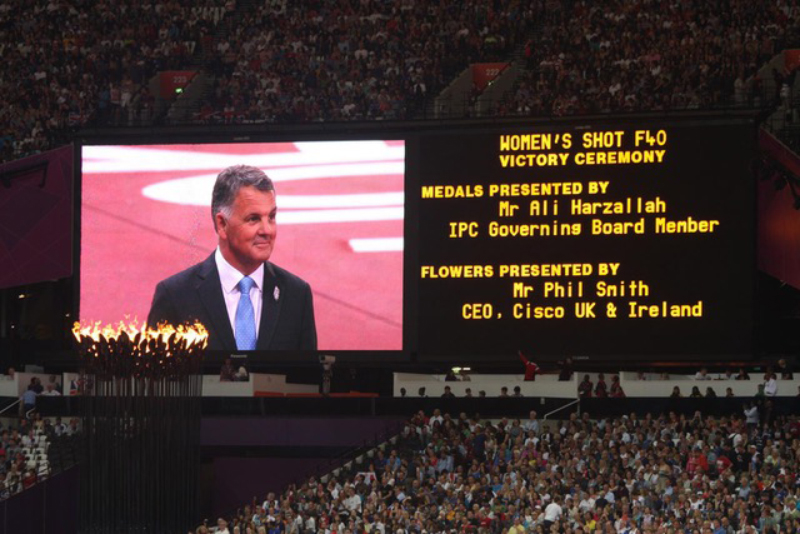

His eyes light up as he talks about his career highlight – Cisco’s involvement in the 2012 London Olympics. As a keen triathlete who qualified three times for Team GB, it’s no surprise Smith was in his element at the games.

He believes 2012 marked a turning point for the country; at that time, companies invested in the UK partly because of its “great people with really amazing skills”.

But we have “lost a bit of that age now”, he admits. “Since 2012, it feels not quite so compelling, with Brexit and all the other things that have happened.”

Lessons from the past

Smith was motivated to apply for the Skills England role having seen how the government tends to “start all over again” with new bodies and “throw all that good stuff away”. He did not want to see mistakes repeated.

Charlie Mayfield, former chairman of the UK Commission for Employment and Skills, is a “good friend” who can pass on lessons from his time at Skills England’s predecessor quango, which was disbanded in 2017.

Smith himself has impressive experience as a chair of government advisory bodies, including e-skills UK (the sector skills council for the IT industry and now part of trade body techUK), which helped the government create the essential digital skills framework and the first degree apprenticeships, and the Digital Skills Partnership which sat within the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. When this partnership “started to lose its way because of all the ministerial changes” after Covid, Smith urged ministers to create a digital skills council instead. The council was recently “revived” by this government, and Smith now chairs it within the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology.

With “little enough government money around”, he is urging departments outside of the DfE to “use the capability” of Skills England.

But he knows from experience “how confusing it can be” dealing with different government departments.

A jumbled up song

Smith refers to an old Eric Morecambe phrase to describe the present skills system: “I’m playing all the right notes, but not necessarily in the right order”.

Although there are “lots of great components”, the system is “very hard to navigate and complex – it isn’t working at all”, he says.

He puts much of this down to a marketing and communications problem and wants Skills England to “help simplify the system”.

Smith confirms that marketing the skills system will be part of Skills England’s brief. But in the meantime, the government is cutting funding to the very organisations that market and communicate components of the skills system to young people, such as the Apprenticeship Support and Knowledge (ASK) programme.

Smith brushes this off. “Changes in funding routes happen all the time in government, whether that’s right or wrong. I haven’t found, talking to ministers or officials or anybody else, that anybody has any lack of desire to try and communicate better and make it more easy for people to get around the system.”

FE providers hoping Smith will help them push ministers for more money will be disappointed. He does not believe that “just putting a lot of money into FE fixes the problem”.

“The bigger problem is how people actually get pathways through careers of which FE might be relevant for some sectors and not for others,” he adds. “We have to think of this as much more of a system problem.”

In light of anticipated cuts to level 7 apprenticeship funding, he would encourage employers to reach into their own pockets to continue this training. He also suggests industry could support learners through their colleges or university pathways.

“Certainly when I ran a business, I didn’t sit there going, ‘right, I’m not going to train my people unless government give me some money’,” he says. “We need to encourage industry to recognise this is a shared problem, not a government issue, and government to realise it’s not just an industry issue.

“There’s something about looking at solutions rather than just throwing rocks at each other, which has been the narrative for quite a while. Government’s natural tendency is to create more and more stuff. And that just confuses the system.”

Part of Smith’s role is to work with regional mayors, and he wants combined authorities to share their “best practice and models” with Skills England to deploy to other areas. Smith last week told Greater Manchester mayor Andy Burnham to “help me support other regions” because “if the rest of the UK is falling apart, that doesn’t help Manchester”.

Voice consolidation

But with “a million voices and opinions” in the system, Smith knows it is impossible for Skills England to hear and satisfy them all.

The answer he believes lies in finding a “constructive way” to listen and “making sure we’ve got the right groups consulting with us, and nothing exclusive”.

He praises how Mark Reynolds, group executive chairman of Mace Group, “rallied [the construction] industry around” to present constructive solutions to Skills England and DfE around his sector’s skills shortages.

The government’s subsequent pledge of £600 million to train 60,000 more construction workers over four years, is “thanks to not just his lobbying, but his leadership”.

Let’s move quicker

Smith hopes that a year from now, Skills England will be collaborating with all of the major industrial strategy sectors in a “very constructive way”. It will also be starting to put measures in place to simplify the system and help people navigate it.

But things do not appear to be moving fast enough for him yet. “The truth is, we need to do it quickly”, he warns. The pace of AI rollout could mean we are “creating skills that are not relevant in a year’s time”.

He believes there are “already things happening” to improve the system but “we need to get them out there” and be “much more open and transparent about them”.

“I’d like to see a bit more transparency in the system overall,” he adds. And with that, he is off to another meeting.

Your thoughts