Growing numbers of children in custody cannot access education due to violence and prison staff shortages, the chief prisons inspector has said.

In his annual Children in Custody report, chief inspector of prisons Charlie Taylor said outcomes in young offender institutes (YOI) and secure training centres in England and Wales continued to be “worryingly poor”.

A survey of 12 to 18-year-olds in custody found 61 per cent reported spending more than two hours out of their cells on weekdays in 2024-25, a 11-percentage-point drop from the year before.

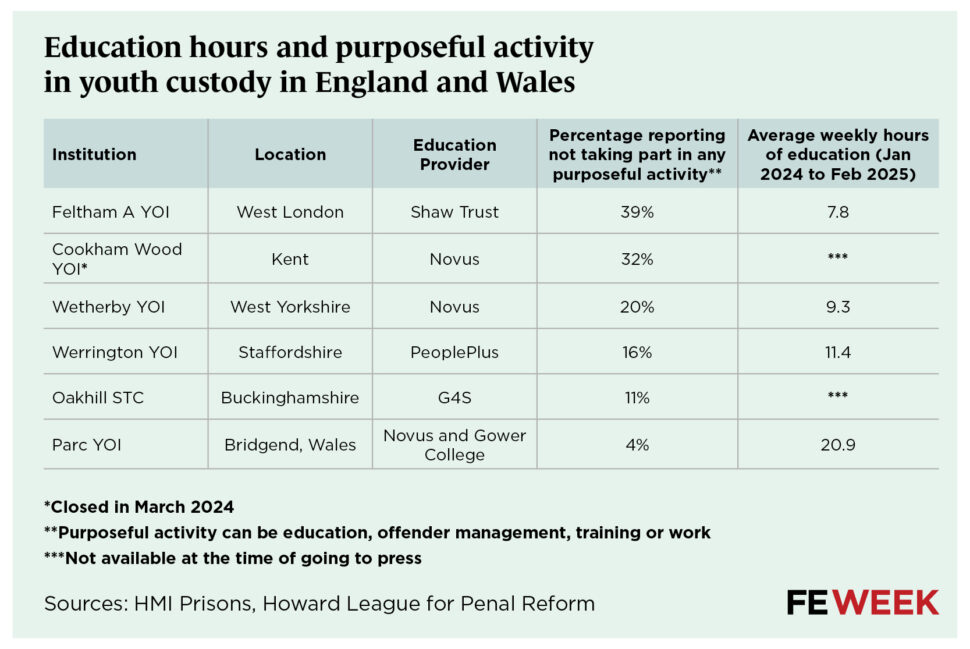

Meanwhile, at Feltham A YOI, only 33 per cent of children said they spent more than two hours out of their cell, and 39 per cent said they were not doing any education, behaviour programmes, training or paid work.

Taylor said: “When children make it to education or other activities, the quality on offer is rarely good enough and sessions are often restricted or curtailed because of staff shortages.”

Many children were “simply unable” to take part in productive activity during their time in custody due to a combination of “weak relationships, a lack of motivation, and high levels of unpredictable and often reckless violence”, the report found.

Violence in youth custody is also worse than in adult prisons due to severe staff shortages and too much time spent in cells due to “overly restrictive” rules on children mixing, creating a “vicious cycle” of isolation, frustration and poor relations with staff.

‘Painfully upsetting’

Andrea Coomber, chief executive of the Howard League for Penal Reform, said: “Prison is no place for a child, and these painfully upsetting survey responses from children trapped in the system explain why. They chime with what the Howard League hears consistently through its legal advice line.”

The report’s findings are based on 375 survey responses from the approximately 400 children held in Feltham A, Wetherby, Werrington and Parc YOIs, and Oakhill Secure Training Centre.

It follows a joint thematic inspection review of the YOI estate over the last decade with Ofsted, published last year, which found unlawful levels of access to education and training, unsuitable curriculums and poor-quality teaching.

Taylor believes the key cause of declining educational standards is “poor leadership and collaboration” between governors and contracted education providers – a mix of FE colleges and training businesses.

Figures obtained by the Howard League earlier this year show that in 2024, average hours of education delivered per month fell to as little as 1.5 hours at Feltham A in August last year, while Parc consistently delivered at least 19 hours.

Minister for youth justice Jake Richards told FE Week the report’s findings were “deeply concerning” and said failures in youth custody are a product of “a broken justice system that has been overlooked for too long”.

“Every young person in custody must feel safe and supported, so they can turn away from crime and become better citizens,” Richards added.

The government has now “implemented” three-year improvement plans for each institution to reduce violence and increase time spent in purposeful activity like education, although the Ministry of Justice’s spokesperson did not respond when asked for details of when the plans were agreed or actions they involve.

The government claimed that time ‘out of room’ is gradually increasing at all sites.

In line with the chief inspector’s recommendation, the government said it had seconded staff from HMP YOI Parc – which was praised by the inspectorate for high rates of education and purposeful activity – to share learnings of their success.

Jon Collins, chief executive of the Prisoners’ Education Trust, said: “While young people in the community are starting a new school year or preparing for college or university, young people in custody are sitting in their cell doing and learning nothing.

“They are being failed by a system that is not teaching them the skills they’ll need to thrive as adults. There should be no more excuses. It’s time for a complete reset of youth custody that puts education first.”

Universities and College Union general secretary Jo Grady added: “Prison educators work incredibly hard in very tough conditions, where gang culture and the threat of violence is all too common a feature.

“A review is long overdue into the cost effectiveness and value for money of various multi-million-pound initiatives focused on young offenders.”

Shift to the community

In the last decade, numbers of children in custody fell to a record low of 430, compared to 2,881 in 2008-9 and 1,037 in 2014-15.

However, reports from the prisons and education inspectorates suggest a declining custody population has failed to improve conditions.

This summer Ofsted issued an urgent notification about “profoundly serious and systemic failures” at Oakhill Secure Training Centre, run by private security company G4S, and Taylor slammed management of YOI Feltham A, in west London, for only planning to give children four hours of planned time outside of their cells per day.

A review of children’s social services by Labour MP Josh MacAlister in 2022 recommended phasing out all YOIs and secure training centres within the next 10 years, as secure children’s homes and schools are “almost always better able” to help care for and support young people.

The review found that the MOJ had saved “significant sums of money” by reducing the number of children in custody, but local authorities were bearing increased costs as a result.

In response to a parliamentary question in January last year, the Conservatives said secure training centres and children’s homes cost an average of about £300,000 per child per year, while YOIs cost about £129,000 per child.

Your thoughts