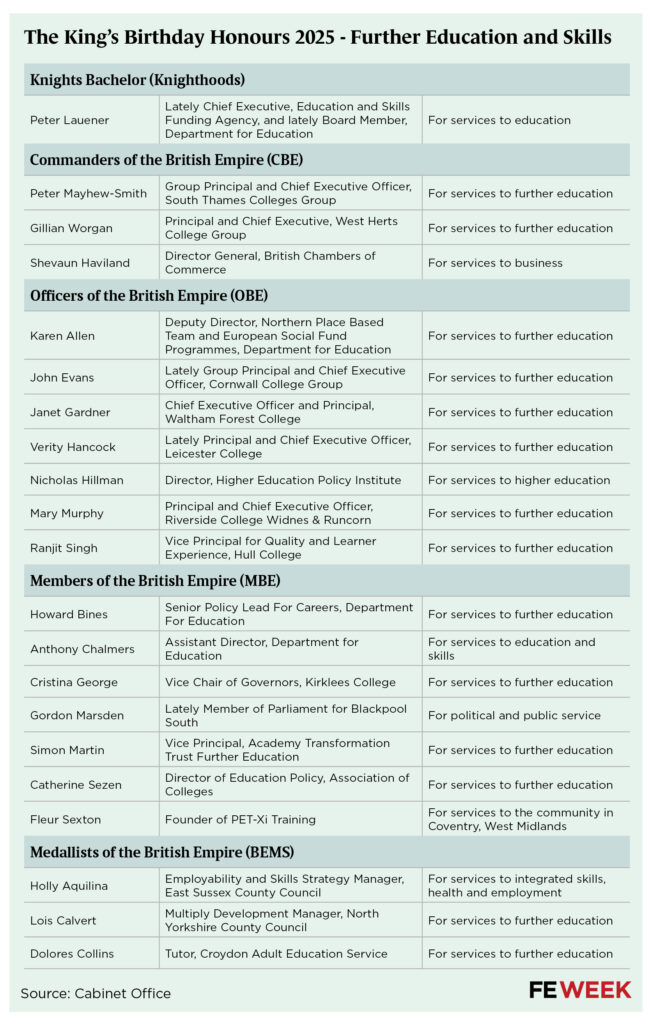

Former chief executive of the Education and Skills Funding Agency Peter Lauener has been knighted in the King’s birthday honours awards.

He’s one of 21 people with links to the further education and skills sector announced as recipients of awards this year – including nine college leaders.

In total, three CBEs, seven OBEs, seven MBEs and three BEMs have been awarded to FE figures.

Lauener, who led the Department for Education’s funding agency from 2012 until 2017, said he was “surprised and delighted” to be knighted.

Since leaving the agency he has chaired large college group NCG and still currently chairs the Student Loans Company and the Construction Industry Training Board.

Lauener said: “In everything I’ve done, I’ve always tried to put learners first, but I know well that it is schools, colleges and training providers who are always first in line in supporting, teaching, training and helping people make the most of their potential.

“So I would like as well to record my thanks to the many great educators, trainers and sector leaders it has been my privilege to work with.”

Picking up a CBE is South Thames College Group’s (STCG) principal Peter Mayhew-Smith, West Herts College principal Gillian Worgan and British Chambers of Commerce director general Shevaun Haviland.

Mayhew-Smith is about to mark eight years at the helm of STCG and has held national roles with the Association of Colleges and advised the Department for Education for two years a member of their principal’s reference group.

He said: “I am deeply honoured to have my work recognised in this way and can only thank the hundreds of remarkable people I have worked with over my many years as a further education practitioner who have made this award a possibility.

“The collective effort of so many great colleagues, governors and partners has enabled South Thames Colleges Group to shine, and we share a strong sense of pride in our service to the wonderful communities of South West London”.

Worgan said she was “deeply honoured and proud” to receive the honour, which is a “testament to the outstanding work” and “dedication” of her colleagues.

She added: “At West Herts College Group, our shared aim has always been to transform the life chances of our students and communities, and I will continue to keep this at the heart of the organisation.”

Worgan has led the college since 2010, growing its Watford Campus’ 16 to 18-year-old student numbers from 3,000 to 5,000, developing a new campus in Hemel Hempstead and merging with Barnfield College in Luton.

OBEs have been awarded to former Cornwall College principal John Evans, former Leicester College principal Verity Hancock and director of the Higher Education Policy Institute Nick Hillman.

Hancock said the recognition of an OBE has given her a “real boost” after being forced to leave her role earlier than planned this year due to cancer treatment.

She added that she is “delighted” to be nominated by governors and honoured to receive an award for working in a sector that “means so much” to her.

Hancock became principal of 8,000-learner Leicester College in 2013, is a board member at the Office for Students, and was previously an executive director at the Skills Funding Agency.

John Evans, who has led several west country colleges, said he feels “a little overwhelmed” to receive his OBE.

Evans, who retired as The Cornwall College Group (TCCG) principal last year, said: “This award means a great deal to me, but it’s really a tribute to the students, colleagues, and communities who’ve been part of the journey.

“FE is blessed with an amazing workforce that despite the critical underfunding in the FE sector, always puts the learner first and springboards them onto their next steps. This was certainly the case at TCCG.”

Riverside College principal Mary Murphy said her OBE is a “collective recognition” for the local community, which “consistently nurtures potential and creates opportunities for all”.

She added: “I’m proud to lead a college that supports learners who go on to become professionals across every sector.

“With this award, I will continue to champion the achievements of young people and adult learners across Halton and the wider Liverpool City Region.”

Murphy began her education career in 1996 and took the reins at the ‘outstanding’ rated college in 2013.

Fellow OBE recipient Janet Gardner, Waltham Forest College principal, said: “This honour reflects the collective commitment and dedication of everyone at Waltham Forest College and the wider FE sector, who work tirelessly every day to transform lives through education.”

Gardner has led the ‘outstanding’ Ofsted-rated college since 2020, added: “I am a product of Further Education, having attended further education colleges both as a young person leaving school and as an adult to retrain.

“I am truly humbled and honoured to receive this recognition for the sector that has given me so many opportunities”, she added.

MBE awards went to Gordon Marsden, former Labour MP and shadow minister for higher, further education and skills, Howard Bines, a senior DfE policy lead for careers, and DfE assistant director Anthony Chalmers.

The Association of Colleges director of education policy Catherine Sezen, who also received an MBE, said: “This is recognition of the hard work of the team I work within, as well as the college staff we engage with daily and who provide us with the evidence we need to speak out on their behalf.

“It makes me very proud to represent the views of this incredible sector.”