Fears are growing over the creation of a postcode lottery for adult learners, leading one devolved area to seek special treatment from the Department for Education, FE Week can reveal.

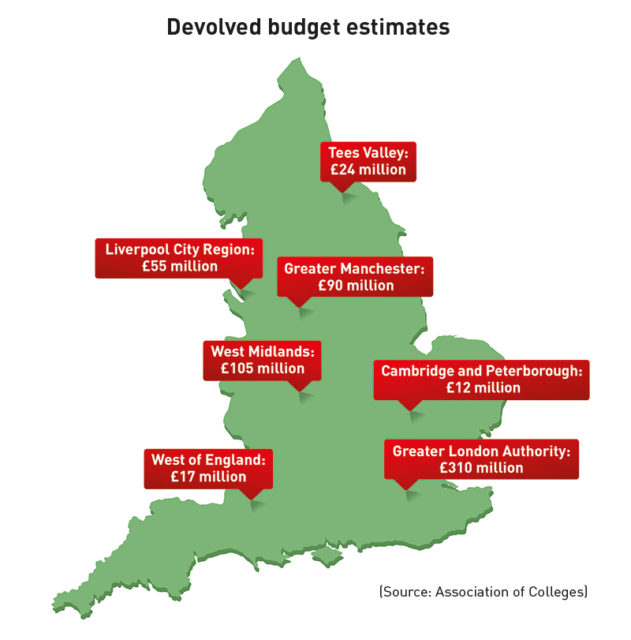

From August 2019, more than £600 million of the £1.5 billion adult education budget will be devolved to the seven mayoral combined authorities. However, these authorities will only be able to fund students who live within their boundaries.

Guidance on AEB devolution, published last month, confirms there will be “no direct reciprocal agreements between the Education and Skills Funding Agency and any mayoral combined authority or Greater London Authority arrangements to fund residents who travel to learn across boundaries from devolved areas to non devolved areas, or vice versa”.

This change could have a big impact on the number of learners accepted by colleges inside the seven devolved areas – Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, Greater Manchester, Liverpool City, Sheffield City, Tees Valley, West Midlands and the West of England – and London, as well as the institutions nearby.

With the prospect of colleges and providers being forced to check postcodes at enrolment, and out of area learners being turned away, FE Week has taken a closer look at the reality of devolved funding.

Special treatment for London

The Greater London Authority is in the process of trying to negotiate a special agreement for the capital which would allow for greater flexibility.

A spokesperson said the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, is asking for Londoners to “receive the same treatment as learners from Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland”, rather than England.

“This includes an acceptance that learners from London could be funded if specialist skills training is not available other than outside of the capital and they want to travel to, or live in, other areas of England to study or learn,” he said.

Many colleges outside the capital are used to enrolling Londoners, including Guildford College, Harlow College and North Kent College, while colleges based inside of London but close to the border, such as London South East Colleges, may now face difficulties recruiting learners from outside the capital.

A spokesperson for the DfE said the Greater London Authority had been given “access to information which identifies learner attendance and need”.

“This is a significant step that will give local areas the opportunity to better meet local economic needs,” she said, adding that the authority is able to enter into a funding agreement “with any provider, no matter where that provider is based, to fund learners who live there”.

Concerns from sector leaders

Sector leaders have been unanimous in their warnings about the new policy, which they say could have negative consequences for learners and institutions alike.

Mick Fletcher, FE expert at the Policy Consortium, warned the changes “could cause all sorts of problems”.

“One of the difficulties in running colleges is ensuring class sizes. Even if it’s just one or two students, that could be the difference of a class being viable or unviable,” he said.

“All these negotiations will have to be done by people who haven’t done it before. We’re going to reinvent a whole load of bureaucracy.”

He added: “I think it’s going to be damaging. It’s going to be damaging for some individuals and for some institutions, and it’s going to be an extra cost.”

Stephen Evans, chief executive of the Learning and Work Institute, called on the combined authorities and the ESFA to “take a proactive approach” to make sure learners can continue to find the best courses for them, and to make sure colleges are not subjected to “unnecessary bureaucracy” or uneven funding.

“The measure of the success of devolution will be whether devolved areas can deliver higher quality provision and better outcomes for individuals and employers, without adding extra burdens and bureaucracy,” he said.

Sue Pember, director of policy at Holex, warned that even in cases where colleges do agree contracts with an authority, these contracts will be “numbers driven” and so are likely to “limit a student’s ability to choose”.

“The feature of learner choice has been an important aspect of the English system of FE,” she said.

“It has driven up quality, allowed the best colleges to grow, and it will be a sad day when it is lost.”

Concerns have also been raised that the policy ignores the fact of people often travelling across geographic boundaries for work as well as for study.

Mark Dawe, chief executive of the Association of Employment and Learning Providers, said it would be “sensible” to have more “flexibility” within the devolved funding to use for learners who travel from outside of the relevant area.

“There is growing recognition that in most combined authorities there is significant travel for work outside the combined authority zone,” he said. “This presents a significant issue when looking at workforce rather than residency.”

Colleges fear postcode ‘restrictions’

Harlow College estimates the changes could affect up to 200 of its learners every year who come from both London and the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough region.

The college is particularly concerned about its newly established partnership with Stansted Airport, who work extensively on recruiting learners from London on to their campus.

A spokesperson said the GLA has made contact to try to find a way forward.

He said: “Employers and potential employees increasingly do not work within the geographical boundaries defined by politics.

“It is really important that contracting arrangements do not impede opportunities for people to gain access to better employment and training. There appears to be no proposed flexibility in rules related to postcodes.”

Ian Pryce, chief executive of Bedford College, said he was concerned the devolved budgets are “likely to restrict rather than increase opportunities” and “increase the complexity for colleges”.

“I really don’t like the idea of us having to say to someone from St Neots ‘these are all the courses we do but you can only do these ones because of your postcode’.

“I hope it won’t come to that, and also hope we don’t see devolved authorities using funds to favour their own adult provision departments or creaming off money for admin.”

However, he added that the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough combined authority has been “excellent at involving us and wants us to carry on as normal for now”.

Sean Scully, director of student experience at Oaklands College, which takes learners from London and Cambridge, said the college was “aware and fully engaged” and expecting “very low numbers” of learners would be affected.

“Our initial thoughts are that by staying engaged with the areas we know students are coming from we will greatly reduce any possible impact,” he said.

A spokesperson for the Guildford College Group said it was “aware of the issue” and was still in discussions with the Greater London Authority “to find a resolution for the very few students that this will affect”.

Trouble ahead for colleges with multiple campuses

FE Week has taken a closer look at some of the complications that may arise from the new focus on postcodes.

As the emphasis is placed on whether colleges are inside a combined authority, this may overlook colleges with multiple campuses which can lie outside of boundaries.

The College of West Anglia, for example, was formed in 1998 out of a merger between the Norfolk College of Arts and Technology and the Cambridgeshire College of Agriculture and Horticulture, and a further merger in 2006 added Isle College in Wisbech.

The college is now based over these three campuses but, although Cambridge and Wisbech are contained within the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough combined authority, the third campus, in King’s Lynn in Norfolk, is not.

The College of West Anglia did not respond to requests for comment about what this will mean for the way the college operates, and whether learners in Norfolk will still be able to attend the local King’s Lynn campus.

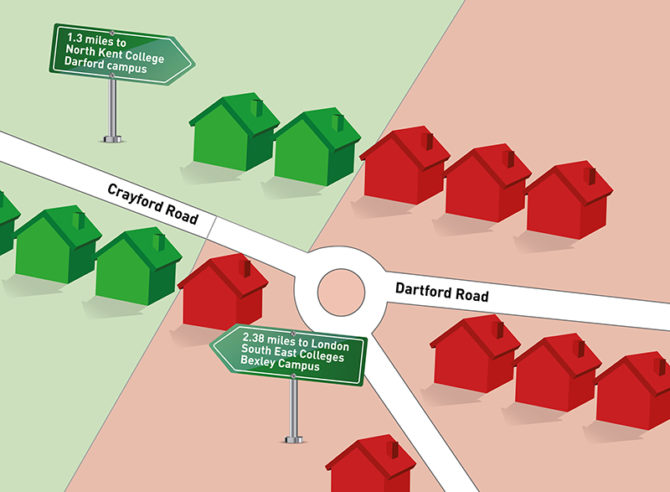

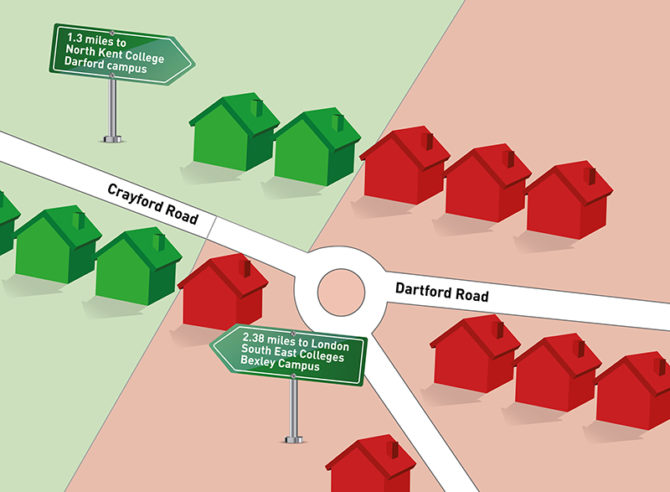

The arbitrary nature of the boundaries also means that some learners living on the same street could be prevented from going to the same colleges.

For example, the edge of the Greater London Authority boundary splits Crayford Road from Dartford Road, where it becomes Kent.

This means that learners who live on the Crayford Road side, in London, will not be funded by the GLA if they enrol at North Kent College’s campus in Dartford, just 1.3 miles away.

And their neighbours who live on the Dartford Road side, in Kent, will not be funded to go to the London South East Colleges’ campus in Bexley, just 2.38 miles away.

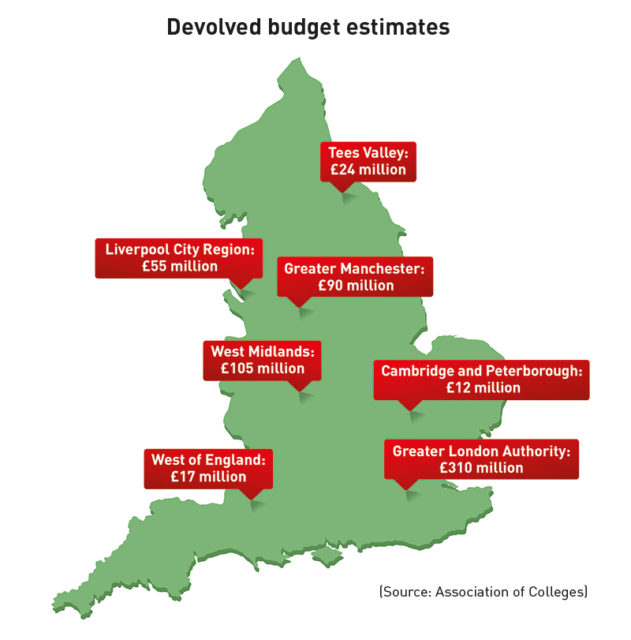

Figures from AoC

Estimates from the Association of Colleges suggest a huge variation in the amount of money that different devolved areas receive.

The Greater London Authority is expected to receive an AEB allocation of £311 million next year, whereas smaller areas can expect a fraction of that amount, with Cambridgeshire and Peterborough in line for £12 million and the West of England expecting £17 million.

The AoC’s estimates, based on data from 2016/17, suggest that 62 colleges are contained within the boundaries of the combined authorities and GLA, which will share £342 million from the devolved budget but just £42 million in separate funding from the Education and Skills Funding Agency.

There are 168 colleges not based within a combined authority, which will share £401 million from the ESFA but will be entitled to split just £81 million from the devolved budget.

Speaking at the AoC conference last week, its deputy chief executive Julian Gravatt said: “I think effectively what we will see is the devolved authorities will want to deal with fewer colleges and providers, and will effectively localise.”

Asked about concerns over a postcode lottery, he told FE Week: “It would be much better if the DfE and the combined authorities could agree a cost transfer arrangement to avoid new bureaucratic obstacles.”