With little fanfare, the National Retraining Scheme is being developed. Research is being done to ensure it will provide advice and opportunities that are attractive and relevant to people’s needs, says Fiona Aldridge

Before the current saga of Brexit deals and no-confidence votes, you might recall the Conservatives’ 2017 manifesto commitment to “help workers stay in secure jobs as the economy changes by introducing a National Retraining Scheme”.

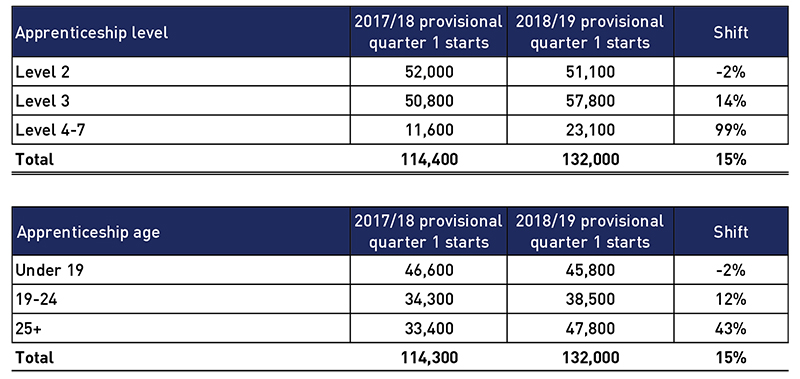

Eighteen months later, we still know very little about the NRS, though a recent parliamentary question confirmed that it will be targeted at adults aged 24+, without a degree, who are in work – with a focus on those in occupations at risk of technological change.

But while details of the scheme are sparse, it is being developed.

Government departments have been working with each other and other stakeholders to understand, then meet, the needs of the people and businesses who will use it.

So, what does the evidence from the Department for Education’s user research and the cost and outreach pilots, supported and evaluated by the Learning and Work Institute, say about how the NRS should operate?

National: Given the pace and scale of technological and economic change, it is critical that all adults can develop their skills and retrain throughout their lives. This must be a national priority; and central government has a key role to play in leading policy development, setting a national framework and ensuring that such a system is appropriately funded and valued.

However, evidence from the cost and outreach pilots clearly demonstrates that robust local leadership and co-ordination is vital in ensuring effective delivery. A key challenge is to develop a coherent national framework that can be shaped and implemented locally to meet the needs of local people and businesses.

The scheme must be able to flex around people’s wider commitments

Retraining: Wide-ranging estimates exist about the number of jobs that will be replaced or changed significantly by technology. However, research shows that few people believe their job is at risk.

Even when this threat hits home, many adults do not seek out information and advice about retraining opportunities – or even know to do this. Those who do try may be unable to find provision that meets their particular needs or that flexes around their wider commitments. Indeed, user research clearly shows that adults in this position are more concerned with finding a job rather than a training course. Thought is being given as to how the NRS will provide high-quality opportunities for people to develop their skills or retrain without taking them out of the labour market.

Scheme: We already have a plethora of short-term initiatives; there is no appetite for another. Instead, employers have been clear that any new scheme must integrate with existing systems and fit coherently with wider government expectations around their involvement in skills development.

Adults too, particularly those who are traditionally least likely to train, are also unlikely to engage just because there is a new scheme in town. The NRS needs to deploy creative ways of reaching them, and must ensure that the support and training on offer is attractive and relevant to their needs. Early findings show that, while social media is most effective in communicating a range of messages to the greatest number of people, adults are more likely to take action following face-to-face contact.

Officials developing the NRS are having to think creatively about how people’s natural contact points can be used to engage them in thinking about retraining, and what sort of offer will best help them to secure good work.

The call for “no more talking, more action instead” is understandable. Indeed, our research shows that participation in adult learning is at a 20-year low, and that those who could benefit most from retraining often have least opportunity to do so. But perhaps the lesson to be learned from other areas of skills policy is that taking time to shape evidence-based policy, rather than rushing out under-developed reforms or chasing big targets, might serve us better in the long run.