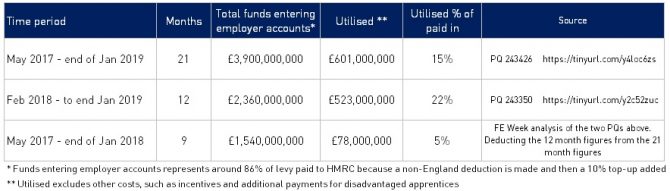

Employers used 22 per cent of their apprenticeship levy funds in the 12 months to the end of January 2019 – a huge fourfold increase from the 5 per cent drawn down in the first nine months of the policy.

The skills minister Anne Milton revealed in a parliamentary answer yesterday that between May 2017 and the end of January 2019, levy-paying employers “utilised £601 million of the funds available to them to pay for apprenticeship training in England”.

This amounts to 15 per cent of the £3.9 billion total funds entering employers’ accounts in the same period.

In a separate parliamentary answer from last week, Milton revealed that in the 12 months from February 2018 to January 2019, £523 million, or 22 per cent, of the £2.36 billion received into employers’ apprenticeship service accounts had been drawn down.

FE Week analysis of the figures used by the minister shows that in the first nine months of the levy, from May 2017 to January 2018, £78 million of the £1.54 billion (5 per cent) paid into employers’ accounts was used to cover training costs (see table below).

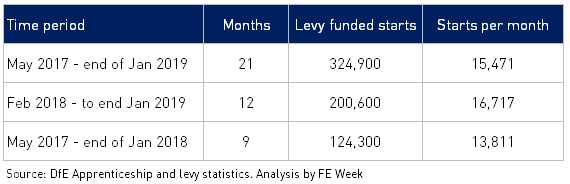

Levy funds usage has therefore increased fourfold, but apprenticeship starts have only increased by one fifth (21 per cent).

Funding is automatically drawn down every month for the duration of the apprenticeship so as new starts are taken on the monthly usage, percentage rises much faster than the starts as it is includes some of the cost of the starts in previous months.

This monthly funding and the fact that on average apprenticeships are now costing more than double the forecast, goes some way to explain why the Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education and the National Audit Office warned of a budget overspend in the future.

Milton explains in the parliamentary answers that the figures do not include other costs that the levy pays for, such as funding apprenticeships for small, non-levy paying employers, for English and maths qualifications and for extra support for apprentices who are care leavers or have special needs.

Large employers have been made to pay the apprenticeship levy since it was launched in April 2017. After a deduction for non-English employees and a 10 per cent top-up the monthly levy value appears in the employer apprenticeship system account, which they have two years to use.

In March, Keith Smith, the Education and Skills Funding Agency’s director of Apprenticeships, told the public accounts committee that employers are expected to lose around £12 million in May, or 9 per cent of what they paid in April 2017, when the first ‘sunset period’ arrives.

And in a webinar with FE Week during the Easter break, the government admitted for the first time the vast majority of the £400 million underspend from the Department for Education’s apprenticeship budget was taken back by the Treasury.

Asked how much cash the Treasury clawed back in the financial year to April 2018, Milton replied she “can’t give exact figures”, and referred the question to Smith, who said it was “just over £300 million”.

There’ve been many concerns raised that employers are not spending their funds quickly enough. The NHS, for example, told FE Week in March that it expects to lose a fortune when unspent apprenticeship levy funds begin to expire from May.

Recent policy changes have aimed to increase levy spending. From this month, levy-paying employers will be able to share more of their annual funds with smaller organisations, when the levy transfer facility rises from 10 to 25 per cent.

The 10 per cent fee small businesses have to pay when they take on apprentices has also been halved this month.

The government had hoped the apprenticeship levy would encourage more employers to invest in training and help it hit its manifesto target of three million apprenticeship starts by 2020. However, starts have fallen dramatically since its launch.

The latest figures, released on March 28, revealed that apprenticeship starts for January were down 21 per cent on the same month in 2017 before the levy was introduced.

FE Week analysis shows that an average of 85,246 starts are needed every month over the next 15 months to reach the three million starts target. Since May 2015, the average has been 38,251.