A confidential document that shows the criteria the government used to choose the level 3 courses in the prime minister’s lifetime skills guarantee has been leaked to FE Week.

It shows the methodology adopted by the Department for Education involved wage outcomes, alignment with government “priorities” and the “ability to address labour market need”.

The list of nearly 400 qualifications that made the cut, which will be available to adults to study from April for free if they do not already hold a full level 3 qualification – equivalent to two A-levels – has been unveiled today but controversially excludes major economic sectors such as hospitality, tourism, media and arts.

So how did the government decide which courses were in and which were out? The documents show a two-step approach was used. Here are the details.

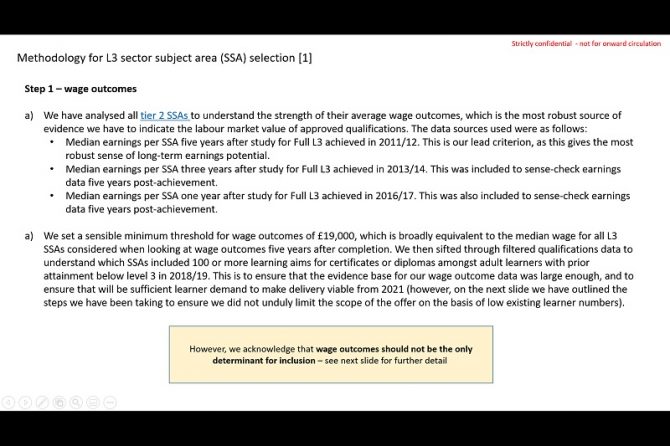

Step 1 – wage outcomes

Firstly, the DfE analysed the existing sector subject areas (SSAs) to “understand the strength of their average wage outcomes, which is the most robust source of evidence we have to indicate the labour market value of approved qualifications”.

The data sources used were as follows:

-

- “Median earnings per SSA five years after study for full level 3 achieved in 2011/12. This is our lead criterion, as this gives the most robust sense of long-term earnings potential.

- “Median earnings per SSA three years after study for Full L3 achieved in 2013/14. This was included to sense-check earnings data five years post-achievement.

- “Median earnings per SSA one year after study for Full L3 achieved in 2016/17. This was also included to sense-check earnings data five years post-achievement.”

The DfE says it then set a “sensible minimum threshold” for wage outcomes of £19,000, which is “broadly equivalent to the median wage for all level 3 SSAs considered when looking at wage outcomes five years after completion”.

“We then sifted through filtered qualifications data to understand which SSAs included 100 or more learning aims for certificates or diplomas amongst adult learners with prior attainment below level 3 in 2018/19,” the document continues.

“This is to ensure that the evidence base for our wage outcome data was large enough, and to ensure that will be sufficient learner demand to make delivery viable from 2021.”

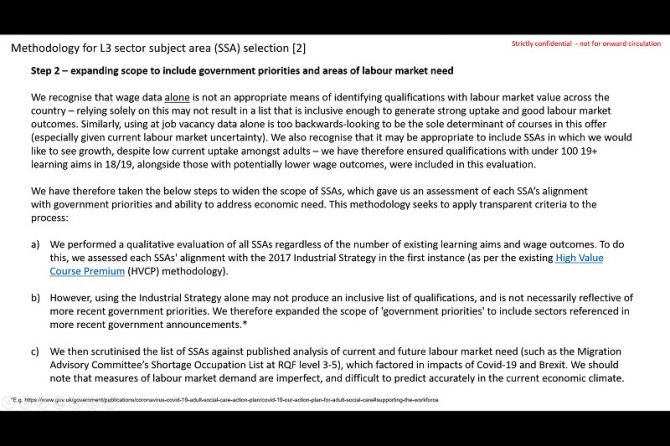

Step 2 – expanding scope to include government priorities and areas of labour market need

The DfE says it acknowledged that wage data alone is “not an appropriate means of identifying qualifications with labour market value across the country” and that relying solely on this “may not result in a list that is inclusive enough to generate strong uptake and good labour market outcomes”.

Recognising that it may also be “appropriate” to include SSAs in which the government would like to see growth, despite low current uptake amongst adults, the department ensured qualifications with under 100 19+ learning aims in 2018/19, alongside those with potentially lower wage outcomes, were included in this evaluation.

“We have therefore taken the below steps to widen the scope of SSAs, which gave us an assessment of each SSA’s alignment with government priorities and ability to address economic need,” the document explains.

- “We performed a qualitative evaluation of all SSAs regardless of the number of existing learning aims and wage outcomes. To do this, we assessed each SSAs’ alignment with the 2017 Industrial Strategy in the first instance (as per the existing High Value Course Premium (HVCP) methodology).

- “However, using the Industrial Strategy alone may not produce an inclusive list of qualifications, and is not necessarily reflective of more recent government priorities. We therefore expanded the scope of ‘government priorities’ to include sectors referenced in more recent government announcements.

- “We then scrutinised the list of SSAs against published analysis of current and future labour market need (such as the Migration Advisory Committee’s Shortage Occupation List at RQF level 3-5), which factored in impacts of Covid-19 and Brexit. We should note that measures of labour market demand are imperfect, and difficult to predict accurately in the current economic climate.”

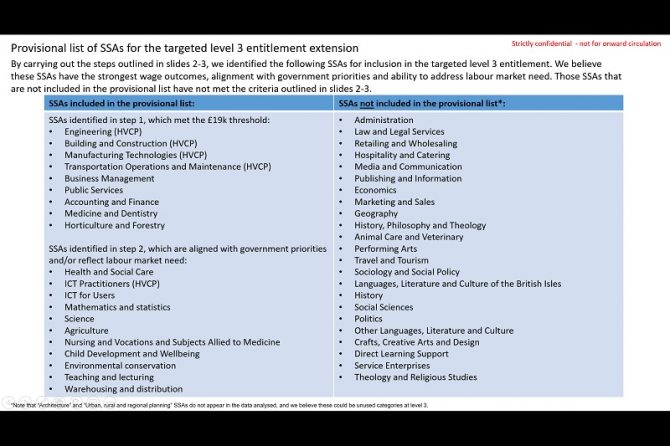

So what qualifications are included?

By carrying out both of the above steps, the DfE identified those SSAs for inclusion in the targeted level 3 entitlement (see list pictured below).

The department adds that they believe these SSAs have the “strongest wage outcomes, alignment with government priorities and ability to address labour market need”.

In total there are 379 qualifications on the list (click here to view in full), which includes a mix of existing vocational and technical qualifications and A-levels.

There are 76 A-levels in total, including 10 A-levels in physics which are offered by different awarding organisations.

Others, like the Advanced Certificate in Bookkeeping, are too small to be counted as a full level 3 qualification.

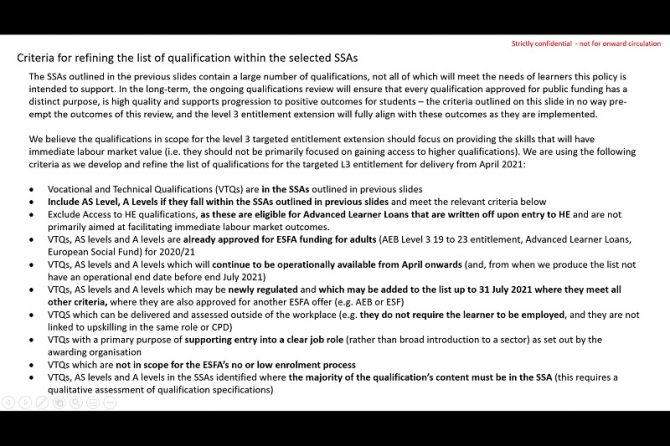

Meanwhile, all Access to HE qualifications have been excluded as these are eligible for advanced learner loans that are written off upon completion of an HE course and are “not primarily aimed at facilitating immediate labour market outcomes”.

The DfE concludes that they believe the qualifications in scope for the level 3 targeted entitlement extension should focus on “providing the skills that will have immediate labour market value (i.e. they should not be primarily focused on gaining access to higher qualifications)”.

Can the list change?

Yes. The DfE says it will keep the list under review and used its confidential briefing to ask awarding bodies to provide evidence for why other qualifications should be added, or why those included should be removed.