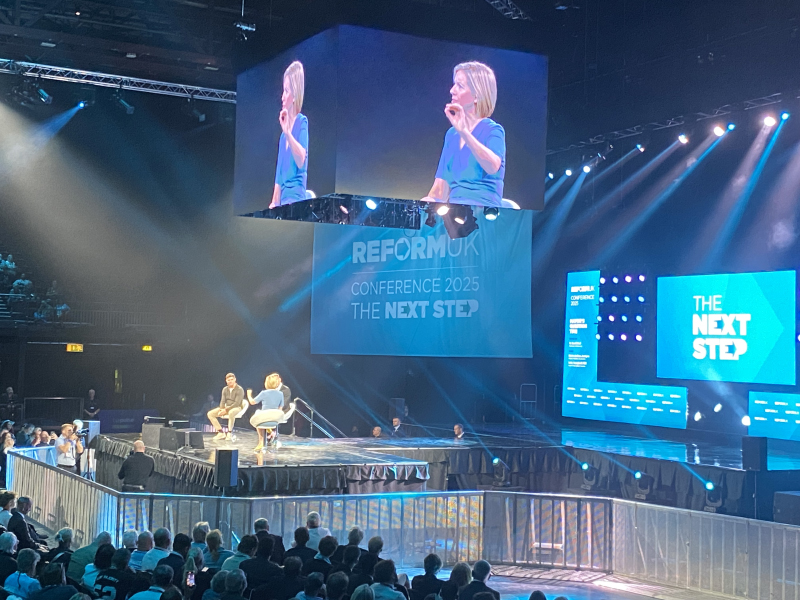

“We’re all ships on a turquoise tide, headed ever closer towards winning the next general election”, began Nigel Farage as he strode on stage and gazed out at a sea of thousands of jubilant faces at Reform UK’s party conference last weekend.

Moments before, a sparkly jumpsuit-clad Andrea Jenkyns, the former skills minister who is now one of Reform’s regional mayors, declared Farage to be “our last chance to truly save Britannia” and led the audience in chanting “Nigel will be prime minister”.

Whether you find their anti-immigration rhetoric to be unhinged scaremongering or the inspired thinking that’s needed to fix “broken Britain”, recent polling suggests Reform could well form the next government. They claim to be the fastest-growing political party in British history.

Skills policy vacuum

Finding out what they could have in store for our skills and further education system wasn’t easy.

The conference featured sessions on cryptocurrency and the car finance scandal, but none on education. It is not a priority for its supporter base. When Reform supporters were asked in a recent poll to pick the biggest issues facing the country, “education and childcare” came fifth from the bottom out of 17 issues, garnering three times less support than “social care for the elderly”.

Similarly, when asked who the government should protect most when making spending decisions, so-called Reformers rated teachers bottom of 13 categories – below “rich people” and “big business”.

Gawain Towler, who sits on Reform’s board and has been described as Farage’s right-hand man, told FE Week that the party is currently in the process of drawing up a skills policy – creating a window of opportunity for the sector’s lobbyists to help shape their policies. The Association of Colleges sent a representative to the conference, but not the Association of Employment and Learning Providers.

Curbing immigration

Currently, theonly mention in Reform’s policy papers to ‘skills’ is to clarify that the only exceptions to the strict limits they would put on immigration would be for those with “essential skills, mainly around healthcare”.

Reform’s head of policy Zia Yusuf, told FE Week that cutting migration would create “issues” around recruiting the engineers needed to meet another of its goals – to “proliferate small modular reactors across the country at unprecedented speed”.

But he indicated that Reform was prepared to pump more money into reskilling British workers.

Visas for skilled migrants would “only ever be sanctioned if we are simultaneously launching the most audacious and unprecedented scale-up process to upskill and train British people in those jobs…and yeah, that will take funding.”

The “challenge” of plugging skills gaps currently filled by migrants was why Reform would consider scrapping the two-child benefit cap.

“You can tell we’re serious about cutting net migration to zero because at least because we’re talking about such policies,” he said, adding that they have “a little bit of time to put this stuff together”.

Towler indicated that a Reform government might use more bursaries as incentives to train people to fill critical skills shortages. He claimed that when the nursing bursary was cut under George Osbourne as chancellor, 50,000 fewer British people trained as nurses and the same number then had to be imported from overseas. (FE Week could not corroborate those figures).

“We made it harder for British people to do these things,” he added.

More ‘trade’ skills

Towler said that “underpinning our agenda” was getting young people to “learn a skill” rather than getting “a big debt” for “something that’s going to be killed by AI”.

He claimed that the advance of AI would make Surrey “like Cornwall was when the mines closed”, as “middle-ranking white collar work is fucked”.

“It’s going to be a long time before AI can do your gardening, landscaping, smaller engineering, mending, fixing, making things work. So there will be a lot of positivity in that direction.”

Similarly, Farage said: “Let’s start teaching kids at school trades and services” and quipped that “one thing that AI will not replace is the local plumber”.

He wants to set up new regional technical colleges for plumbing, electrical trades and industrial automation in Wales if they win power there next year.

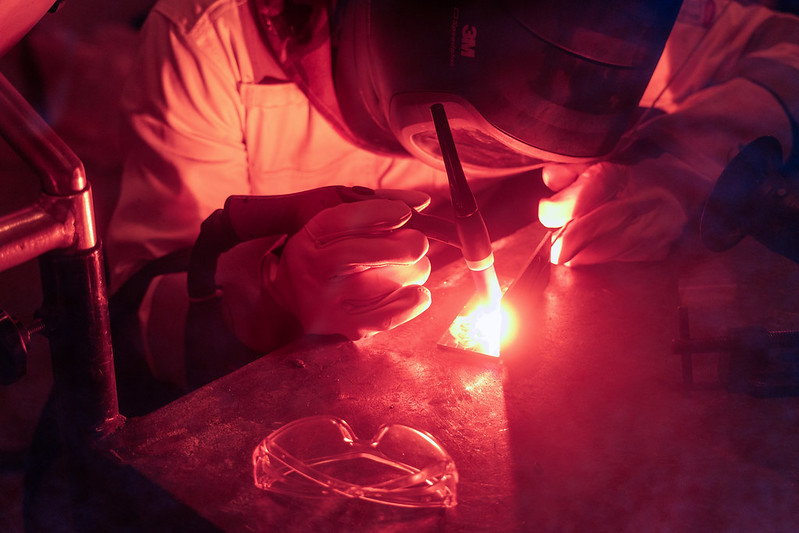

The first such college in England appears to be planned by Lincolnshire mayor Jenkyns, who told FE Week she is committed to opening “the biggest and best trade college there, which can serve the country” and where “young people can learn building, plumbing, welding and other trades that are the backbone to rebuild our nation”.

One Lincolnshire principal told FE Week, “I thought we already were”.

Jenkyns is taking inspiration from the “amazing” CATCH, an industrial skills centre near Grimsby.

“I’ve never been to a college with such cutting edge facilities, and industries pay for that. Isn’t that a great model? We know that colleges are struggling. Can you imagine if we get industry talking to colleges, investing so that they have got school and college leavers with the right skills to go to a job in their area?”

She described her plan for Lincolnshire as a “Reform blueprint” to create “a microcosm of what Reform can do in government”.

As skills minister, Jenkyns said she had been “disgusted that literacy and numeracy has been on a downward spiral for the last decade,” and believes this “might be to do with closing of a lot of colleges.”

She had wanted to “bring a parity of esteem between vocational, technical, academic and trades” as “for too long, colleges have been seen as the poor relation”.

She will be “trying to push” for that parity on Reform’s decision-making board which she was appointed to last month.

HE ‘waste of time’

Universities’ current financial pressures might just implode under a Reform government.

The party has pledged to limit the number of undergraduate places to “well below” current levels, enforce minimum entry requirements and mandate all universities to offer two-year undergraduate courses.

Yusuf said there were “way too many young people taking on degrees”, some of which “do not make them more employable [or] earn more”.

Towler sees “a lot” of higher education as “a complete fucking waste of time” and launched a tirade against Blair’s government for expanding university provision. “We now have…people who are highly educated doing basically grunt work. [It’s] a disaffected population, as people feel entitled to something marvellous when there’s nothing marvellous there.”

Jenkyns – who said she was “torn” as a single mother over whether she would want to be skills minister or education secretary under a Reform government – when asked whether she would bail out bankrupt universities, responded: “Do we need as many universities, or do we need a more diverse climate?”

‘Woke’ curricula

The most vehement anger was directed at the education system’s “communist” biases.

Yusuf said the party had to “stop schools from becoming indoctrination camps”, with universities being “even more so indoctrination camps”.

The curriculum and assessment review, currently poised to make its recommendations to government, has pledged to “look across the curriculum to examine where opportunities exist to increase diversity in representation”.

This might jar with Reform’s own pledge to allow “no discussions on gender-questioning, transitioning, or pronoun swapping” in schools, and to teach history in a “patriotic way”.

Jenkyns said the UK should “stop being ashamed of our history…we weren’t perfect, and certain things we should not have done, but it’s about learning from the past…not about trying to silence the past or apologise”.

Reform also wants to cut funding to universities that undermine free speech.

Yusuf claimed his inbox was “absolutely full” with emails from “not just worried parents but kids…admonished by teachers” and “asked to stay behind in class” for saying they “like Nigel Farage”.

“We’ve got to look very seriously at that,” he said.

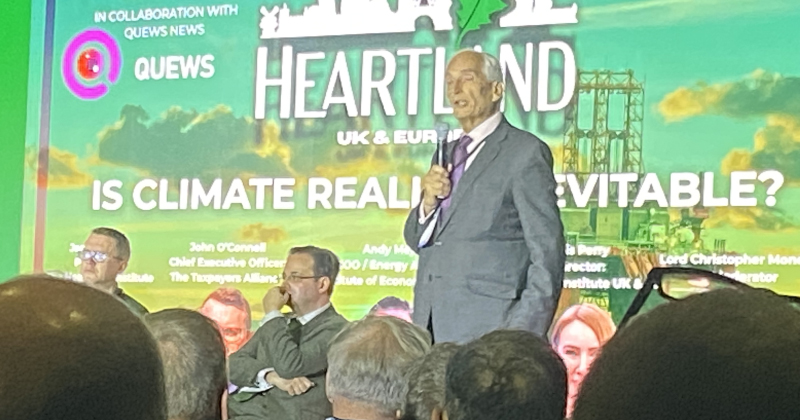

Climate sceptic Lord Christopher Monckton, who believes there is a “sporting chance” he would be made “the Secretary of State, not ‘for’ but ‘against’ the climate change nonsense” under a Farage government, was particularly militant in his views.

Claiming that parents have “absolutely no idea what nonsense is being drip fed into their child’s mind by these wretched communist teachers”, he said there should be a “sound feed for every class, available for every parent of that class” so “the communists will no longer be able to get away with that propaganda without at least the parents finding out about it and raising a stink”.

He also called for making every university lecture, seminar and tutorial “filmed as well as recorded and made publicly available to everybody at all times and permanently for ever”.

Similarly Mansfield MP Lee Anderson, claiming some teachers were “brainwashing our kids”, said that Reform would “root these teachers out and hold them to account”.

“The more you try and indoctrinate children, especially young boys, the more they’re coming to us now, 15-16 year old boys…it’s great.”

George Finch, 19-year-old leader of Warwickshire Council, referred to the “communist conveyor belt of universities” and described how he had dropped out of Leicester University after finding it “depressing”.

“If you want to succeed, you have to keep your head down and be quiet and not say anything. But that’s where I was a bit different. I did say I was a Reform member. Didn’t make many friends.”

But he believes “the world’s changing”, which is why it is “really important” for Reform to take on this agenda.

The other item on Reform’s education agenda is to not only “undo” what Yusuf describes as “the vandalism” this government has done through its pledge to charge VAT on private school fees, but also offer a 20 per cent tax relief on fees.

Devolution disarray

Whereas the last two governments have been in favour of devolving powers to regional areas and reorganising local government, Reform’s central commandbelieves that the country may have bitten off more than it can chew and is reticent about the benefits of devolution.

Towler described the devolution process as “incoherent” and said his party was “not really comfortable with” mayors, despite the party now having two of its own with Jenkyns in Lincolnshire, and Luke Campbell in Hull and East Yorkshire.

He believes that “the idea of governing at Westminster” was a “driving force” for Brexit.

Devolution has been an attempt (by Labour-controlled areas) to “strip from national democracy that electoral authority created at general elections… making it more difficult for [the government] to prosecute their policies right the way down”.

Reform will win mayoralties next year in Essex, “probably” Suffolk/Norfolk and “may well win” Sussex and Hampshire too, which was “was not in the plan” for Labour. “They have now built in whole areas of the country that are going to be run by people in this room today,” he told a panel session.

Meanwhile, “the rapid change” involved with local government reorganisation was “very, very confusing for the average punter”.

Governance: reform and suspicion

This time last year, Reform had eight local councillors across the country; Towler, then Reform’s head of communications, predicted they “might win four councils” in the local elections; “I’m an optimist”.

It now has over 900 councillors and leads on 12 councils.

This has created a “problem of rapid success”. Reform is now “rapidly trying to fill those holes”.

It has formed a ‘Reform Council Association’ to help newly elected party councillors learn from each other.

But there is much suspicion over the intentions of officials in all tiers of government.

Jenkyns said she had already sacked one of her officers and has a “close eye” on another, but also lamented that she was the only mayor in the country without her own special advisor and has “no team”. She is “literally doing a lot of case work myself” which has been “difficult”.

She felt officials at DfE when she was skills minister were often politicised and unavailable, with around six in eight of her private office often working from home. She is insisting on her current staff working from the office.

Highlighting her lack of trust for officials, she said as a DfE minister she had been asked to sign off a £2 million package for a failing college, with £1 million for management consultants; she refused, and civil servants then got it signed off by the Secretary of State.

Calling for people with experience of government to join their mission, Farage said the party was “beginning to see already through the county councils that we run certain obstructions from the civil service being put in our way”.

“I imagine if we win the next election, we may face similar barriers to the kinds of real change that this country needs.”

In his main-stage speech, Farage said having government departments run by MPs “doesn’t work, does it” pledging to recruit “ministers of all the talents” from outside the Commons and “to hell with convention”.

Over in the Lords, Towler said the first act of a Reform government would be to create about 500 peers, which would be “utterly essential” to govern.

Doge days

Reform has been parachuting Elon Musk-style ‘Doge’ units into the areas it runs, on a mission to root out wasteful spending.

Councils’ pressure to make savings, combined with the recent six per cent cut to the adult skills fund, is putting the survival of some adult education centres under threat. Reform-led Derbyshire Council is closing a third (five) of its adult education centres this year and Kent is closing one in Gravesend and consolidating its provision. Its leader Linden Kemkaran told FE Week that “adult education as a whole is something that unfortunately is being cut back because we have no money. We have to slice things where we can.”

With SEND costs ballooning, Reform has hinted that it would cut SEND-related entitlements. Richard Tice said “there is a level of abuse” of the SEND system which will “bankrupt most councils within the next three years”, and Farage has touted “significant” cuts to the welfare bill.

When asked whether she supported restricting the issuing of education, health and care plans, Jenkyns referred to the “need to teach in a different way, because we haven’t got a never-ending pot of money”.

Finch said Warwickshire Council has a SEND deficit of £87 million with SEND transport pressures escalating it next year to £147 million. “We do need to look” at why demand was increasing for SEND services, he admitted.

“Freebies” for migrants

The party’s hardline stance on immigration does not bode well for ESOL provision. As part of cutback plans Kemkaran has launched an investigation into cutting ESOL classes for migrants, suggesting they could use the app Duolingo on their phones instead “for nothing”.

With the investigation “ongoing”, she told FE Week: “if you come to this country, you should learn English. You shouldn’t necessarily expect someone else to pay for that.”

Finch took a similar stance, saying that if migrants were coming here “legally and it’s done properly, then they should already be speaking English…why are we bringing people in who can’t speak English? They’re already not supporting the economy because they can’t communicate.”

There is strong support among Reform supporters for making the requirements for British citizenship more stringent: 96 per cent of Reform supporters endorse the view that immigrants should be required to pass strict language and culture tests before they can become citizens.

Lincolnshire mayor Andrea Jenkyns took aim at the City of Sanctuary network, which helps refugees feel more welcome and which many FE colleges are members of.

“Some of our towns are being pitched to become sanctuary cities for migrants – you know the type – freebies for migrants. But we at Reform say no freebies,” she said.

City of Sanctuary denied that “freebies” are being handed out, pointing out that asylum seekers live on as little as £9 a week. They described English classes as “essential for survival and early integration”.

City of Sanctuary is pausing work with new colleges in 2026-27, after inflammatory narratives about its programmes were widely shared on social media, putting its team under strain.