Suppliers are being sought to bring as many as 4,000 teachers into the further education sector by 2025, as part of an expansion to a major recruitment scheme.

The Department for Education has launched a tender, worth £3 million, for national delivery partners for the Taking Teaching Further programme, which was earmarked for an expansion in the Skills for Jobs white paper last month.

“Given the wider economic importance of FE in raising skills levels and providing a passport to opportunity for young people and adults, particularly through apprenticeships and T Levels,” the prior information notice reads, “we need sufficient numbers of highly skilled teachers in place to deliver high quality, work relevant skills training”.

There is “a very real need” for recruits to have industry expertise and “excellent” teaching skills, as this “is paramount for delivering first-rate FE teaching,” the notice adds.

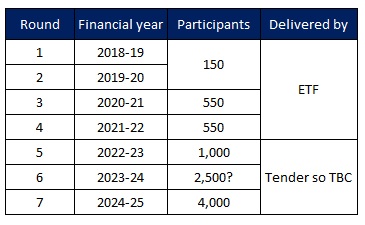

The first three rounds of the Taking Teaching Further pilot, which has been run by the Education and Training Foundation between 2018-19 and 2021-22, offered places to 150 teachers across the first and second rounds, and 550 places were available for round three.

We need sufficient numbers of highly skilled teachers in place to deliver high quality, work relevant skills training

Last Thursday the DfE announced round 4, to support a further 550 places with the full costs of undertaking a Level 5 teaching qualification, reduced teaching workload and other support, such as paired teaching and mentoring in the first year of teaching. A spokesperson for the Education and Training Foundation said they will make more information available in due course.

As the programme expands, the DfE anticipates there could be around 1,000 places on offer in the first year of this contract (round 5) and this would rise to 4,000 by 2025 (round 7).

The three-year contract start date has been set for April 2022, but the prior information notice says it could begin as soon as this December, and it also leaves the option open for the DfE to expand the contract to March 2026.

Organisations which have delivered similar funding programmes are being asked to come forward by the DfE, which is also inviting suggestions and feedback on the proposed content and structure of the programme.

Taking Teaching Further works by funding providers to recruit teachers, and according to the notice, the programme is constructed of a mix of ‘training while teaching’, part-time study, as well as mentoring and work shadowing with a reduced workload in the first year of teaching so recruits can train.

Delivery partners will hand out funding to providers, secure take-up, and provide additional support, including helping to promote the programme.

The much-anticipated Skills for Jobs white paper set aside an entire chapter to discuss plans for expanding and upskilling the further education teaching workforce.

It promised a “significant” new investment in the FE workforce in 2021-22, claiming it would take the total investment in that area to over £65 million.

It also revealed there would be a national recruitment campaign to highlight the benefits of a career teaching in further education, targeted at “high-potential graduates and experienced industry experts”.

A tailored professional development offer for apprenticeship teachers and lecturers, and the introduction of employer-led standards for initial teacher education were also promised.

The DfE will be running a market engagement event for the Taking Teaching Further expansion in the week beginning 22 February. Those wishing to attend have been asked to email HEFE.Commercial@education.gov.uk.