Nearly a third of colleges seeking a teaching excellence framework (TEF) rating this year have challenged their judgment.

The Office for Students today announced the results of the 2023 TEF, the first time the quality ratings have been release since 2019. Gold, silver, bronze or ‘requires improvement’ ratings are handed out based on an assessment of the quality of a provider’s higher education teaching.

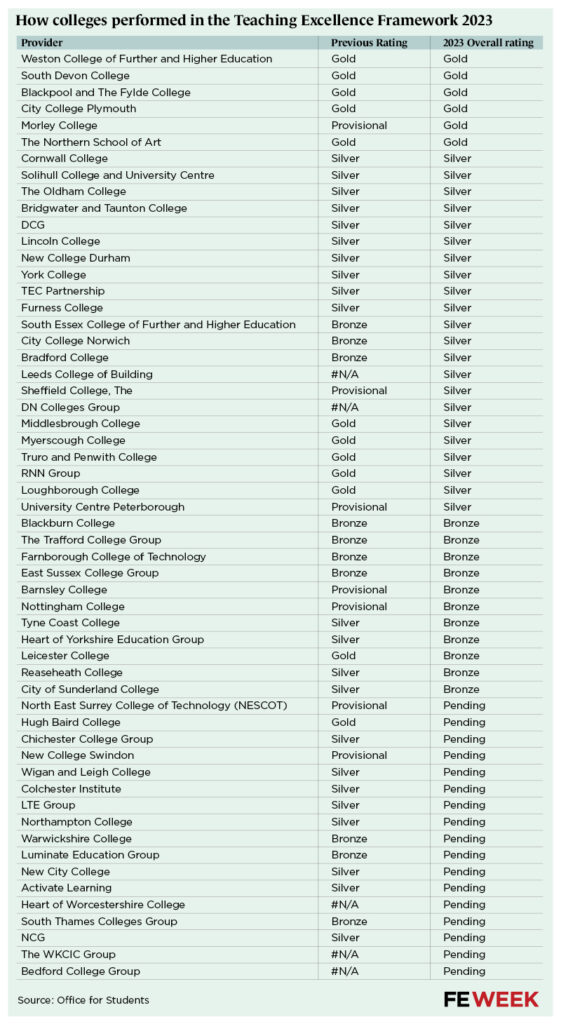

Six of the 56 colleges who were part of this TEF round secured gold, while 22 achieved silver and 11 were given bronze.

But 17, almost a third, of colleges entering TEF have appealed their results, giving them a ‘pending’ outcome.

For the first time this year, HE providers received subsidiary judgements for student experience and student outcomes alongside their overall rating.

The revamped TEF led to nearly a quarter (53 of 228) of all universities, colleges and other HE providers challenging their rating.

Some have complained that the TEF grading process penalised those with higher numbers of disadvantaged students.

In a letter to skills minister Robert Halfon, Frances Corner, warden at Goldsmiths University of London, said not including the number of students eligible for free school meals in the benchmarking for the TEF process was a “significant oversight”.

She said that could have affected performances, after research by London South Bank University showed universities with a smaller proportion of students with free school meal eligibility were more likely to receive a TEF gold rating.

TEF outcomes are determined by an OfS panel using provider performance data alongside evidence submissions from the provider and their students.

No college received the ‘requires improvement’ judgement for their overall rating, but this could change once appeals have been finalised. South Essex did receive ‘requires improvement’ for the subsidiary judgment of student experience, while City of Sunderland College and Barnsley College got ‘requires improvement’ for student outcomes.

South Devon College, Blackpool and the Fylde College and City College Plymouth each secured straight golds, with Weston College, Morley College London and The Northern School of Art achieving gold for student experience and silver for student outcomes.

Dr Andrew Gower, principal and chief executive of Morley College London, said: “As the only specialist adult education institute in the country offering higher education as an integral part of its strategic mission, we are delighted to receive the overall rating of gold with the teaching excellence framework.

“Whatever their age and background, our TEF gold rating means that students can have confidence in a high-quality higher education.”

Blackpool and the Fylde College principal Alun Francis said: “This gold rating is evidence that our extensive efforts for every student and apprentice, and our personalised approaches with wraparound support, are working.”

Three colleges saw their TEF rating improve on their previous score. City College Norwich, Bradford College and South Essex College of Further and Higher Education each moved up from bronze to silver, with the latter also scooping a gold for student experience.

Jerry White, principal of City College Norwich, said the silver rating shows the “quality of our vocational, career-focused higher education stands in comparison with the learning experience and student outcomes available at many prestigious universities”.

“I hope that this will encourage more students to consider the employment-focused Higher Education opportunities that are available to them locally,” he added.

Ten colleges in this TEF round saw their overall ratings decline.

Leicester College dropped from gold to bronze, while Loughborough College, RNN Group, Truro and Penwith College, Middlesbrough College and Myerscough College are now silver.

Susan Lapworth, chief executive at the OfS, said the TEF ratings “clearly demonstrate the excellence on display in universities and colleges”.