The University and Colleges Admissions Service (UCas) has welcomed an invitation for talks on promoting higher apprenticeships.

The organisation, which already matches learners to some higher-level FE courses under the banner of UCas Progress, responded to a call from Business Secretary Vince Cable for it to cover higher apprenticeships.

Dr Cable, during a University of Cambridge public policy lecture, said: “We already have a well-recognised and effective system for applying to university through UCas, which operates independently of government. What is less well known is that UCas also acts as a portal for candidates applying to study Higher National Certificates and Higher National Diplomas, including at FE colleges.

“I have asked my department to work with UCas to examine the scope for integrating higher level apprenticeships into their services.”

Helen Thorne, UCas director of policy and research, said: “Our website encourages students to think about a wide range of future options, including alternatives to higher education such as apprenticeships, and the conventions that we hold across the UK have dedicated ‘CareerZones’ where students can discuss work-based learning. We also email unplaced students with information about a broad range of educational opportunities.

“In UCas Progress we offer a search and apply service that helps younger teenagers make the right choices after GCSEs — whether that is an A-level in maths, a BTec in business or a plumbing apprenticeship.

“This year, around 700,000 young people are using the service and we will be delivering a more comprehensive national service from autumn this year. This will include information and careers advice and the ability to search and apply for courses right across the country. It will be free to use for all learners.

“We look forward to discussing higher apprenticeships with the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills and working together to ensure that students have access to the best possible information as they make decisions about their future education and career pathways.”

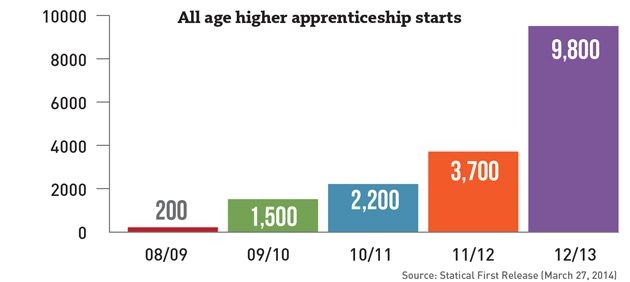

The number of higher apprenticeship starts has rocketed to 9,800 in the last academic year from just 200 in 2008/09 and their potential inclusion by UCas has

been welcomed by sector leaders, including Association of Colleges (AoC) senior higher education policy manager Nick Davy.

He told FE Week: “We’re very supportive of Dr Cable’s comments and the government’s backing for developing higher vocational education in England, including higher apprenticeships.

“Applying through UCas would probably raise the profile of higher vocational education in colleges, but AoC would want to discuss with officials how it would work in practice.

“Applications for higher apprenticeships tend to be made locally, which means it’s not the same as traditional higher education where students apply from across the country, so we need to look at that.”

And Stewart Segal, chief executive of the Association of Employment and Learning Providers (AELP), said: “AELP has been encouraged by the growth of higher apprenticeships over the last two years and welcomes the Secretary of State’s latest commitment to tackling the parity of esteem issue.

“Our members have been taking on school leavers with good A-levels as apprentices for a long time and we saw an increase in numbers when university tuition fees were raised.

“Nevertheless there is still much to be done in terms of increasing awareness about higher apprenticeships and so we are pleased that the government has asked UCas to use its website to promote them as an alternative option.”