City College Coventry principal Steve Logan started in post just this week, and one of the first items on his desk was a requires improvement inspection result from Ofsted.

But with the college having previously received a disastrous report that branded it inadequate, the new grade was welcomed.

In an exclusive Q&A with FE Week, Mr Logan discusses the report — and what’s next for the college.

The latest result must have been the first thing you’ve dealt with at the college. Were you aware of the previous inadequate result and what’s been happening at the college since then?

I’ve been in touch with the college and I’ve been aware of where it’s been going before I came here, but it’s been very welcomed to no longer be inadequate.

It’s a particularly good report and we’ve got some grade twos in there as well. We recognise, obviously, that there’s still a lot of work to do and we’re already on with that journey and I’ve taken a flying start to that this week, along with staff here.

There is an acknowledgement of the work that has been done to turn the college around by leaders, managers and governors, but also teaching staff as well, their expectations of learners being particularly high now. The other bit is this sort of pride that the students felt in the college and the high level of support that they get while they are here.

And the Skills Funding Agency lifted the notice of concern with the improved Ofsted grade, so what is happening next for you?

We’ll be developing an updated post-inspection action plan, so it’s pretty much business as usual for us. We’ve got to maintain intensity of focus on improvement that we had previously, so we’re not going to change that — that’s one of the key messages that I’ll be saying.

We need to focus on the core business, which is the student experience, and most importantly the quality of teaching, learning and assessment. And that will be very much at the heart of the work that I’ll be leading. You will see in the report that there is emphasis on things like target-setting, you know, even greater focus on developing maths and English as key skills for all learners, and other things such as equality and diversity, which we have already done a lot of work on but something that needs further embedding.

We need a little bit longer to try and embed those changes and see that the real evidence and impact that those things are having in terms of retention and achievement and the overall success and progression of learners etc. And probably the only other thing that is going to be a key aspect for us is developing our focus on employability, and through that, increasing the amount of work experience that our learners get.

But we’ve done an awful lot of work already, working with employers to develop employer board in Coventry with our key employers, and they are going to play an increasing role I think in influencing the design of that curriculum, including work experience, in the future. The good thing for me is the route map is there.

What specific things are you going to be looking for? What KPIs [key performance indicators] are you going to be keeping your eye on?

We’ve got some inconsistencies, and you will see the word ‘inconsistent’ a few times in our report. So we’ve got lots of really good practice, both in teaching and learning and assessment, and in outcomes for learners, they’re not the same throughout the college — so I think the key message is, we have got to strive towards greater consistency in all areas so that good practice is shared across the college, and that the outcomes for learners — which are good and improving in many areas — are also good and improving in some of the weaker areas that we know about, which we continue to improve on.

What changes are you putting into place?

I think for us, the keys to the direction the college has taken in recent months around focusing on the needs of Coventry as a city, and our partnership with the local enterprise partnership and the city council, that’s pretty much the only change. We’re going to be focusing very much more about our own learners, our own communities, and their employers, and making that very much the single focus of what we do. And within that, we are looking at the economic needs of Coventry. I think we will be turning our attentions to that broader work of getting people into the labour market, and making our city strong economically. I mean, strive for skills and education of the workforce that’s needed.

Are there any issues in terms of finances or staffing levels?

There are strains on college finances across the sector; we’re no different from any other college, so we’re having to face up to those now. I think the vast majority of colleges are having to make some really difficult decisions about staffing levels now, they’re ongoing, we have recognised that these are difficult times for staff, so having been buoyed by the success of Ofsted, we’re out meeting the realities of reduced funding next year and having to balance our budget — that’s a difficult job for any college, and Coventry is no different.

Nothing has been done yet though, has it?

Locally, at the same time that the Ofsted inspection has been going on, we’ve been having to consult with staff about restructuring and staffing reductions overall for next year, so we’re in the midst of that now but I’m picking it up. But again, I think pretty much almost every college — certainly our region, but elsewhere — is probably in a similar vein. We are having to balance budgets, not just for next year but ongoing, and that will be something that probably we’ll need to continue to do into next year as well.

We have been looking at losing around 70-odd staff across a range of areas really, the whole college. But the positive slant on that is that we have obviously dealt with a majority of those through voluntary severance and through redeployment — and we’re probably down actually now to about only 15 or so compulsory redundancies.To get from that quite high figure down to that low number for compulsory redundancies is testament to the work that the staff and the colleges here, but working with our unions as well. It’s difficult for everybody, but it’s necessary to really put the college on a firm footing moving forward, because financially, all colleges are struggling at the moment to meet those funding issues that are coming along.

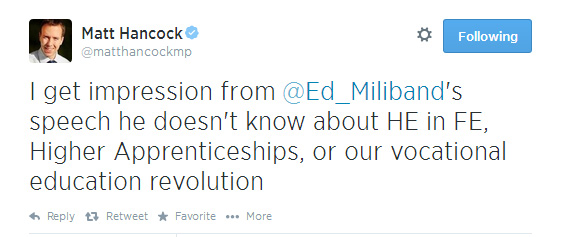

He tweeted: “I get impression from @Ed_Miliband’s speech he doesn’t know about HE in FE, Higher Apprenticeships, or our vocational education revolution.”

He tweeted: “I get impression from @Ed_Miliband’s speech he doesn’t know about HE in FE, Higher Apprenticeships, or our vocational education revolution.”