Over 25,000 young people started a T Level in the fifth year of the government’s flagship qualification rollout.

This marks a 59 per cent increase on the previous year – a rate of growth that a qualifications expert has said is not high enough for the courses to “become the dominant technical offer”.

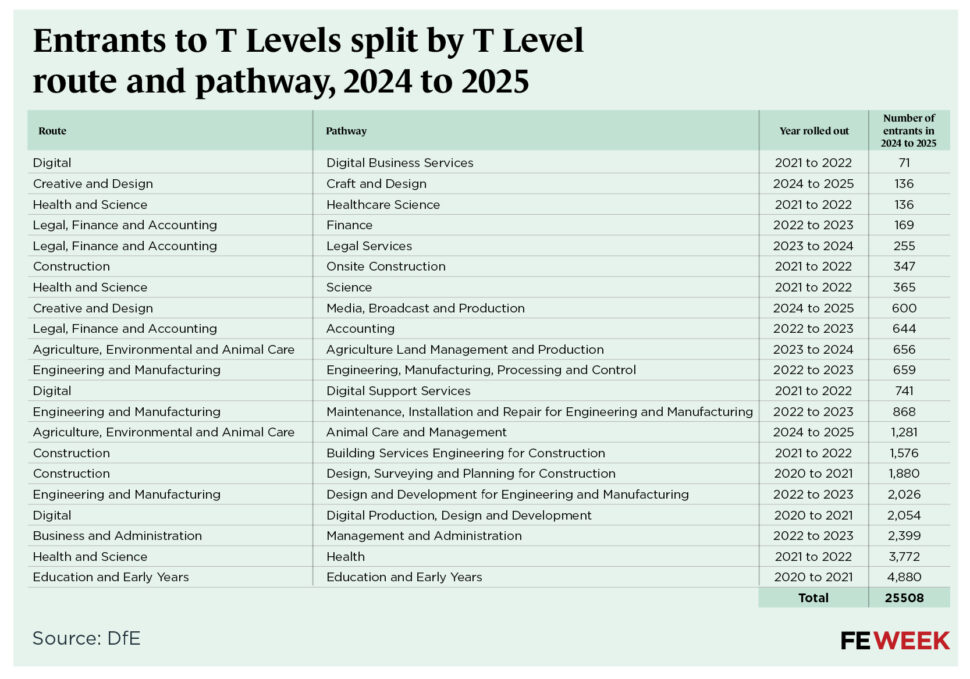

Early years, health and business and admin remain popular T Levels with the majority of starts in 2024-25, according to transparency data published by the Department for Education this morning.

The number of learners starting T Levels grew from 16,085 in 2023-24 to 25,508 in 2024-25. Over this period more than 100 more providers came on board to deliver the qualifications, rising from 254 to 367.

The rate of growth in student numbers was similar to the year prior (58 per cent).

A DfE update today said the numbers shows “real progress in extending the opportunities T Levels provide to more young people”.

Today’s data shows courses such as digital business services and healthcare science continue to struggle to attract learners. They attracted just 71 and 136 students respectively, despite launching three years ago.

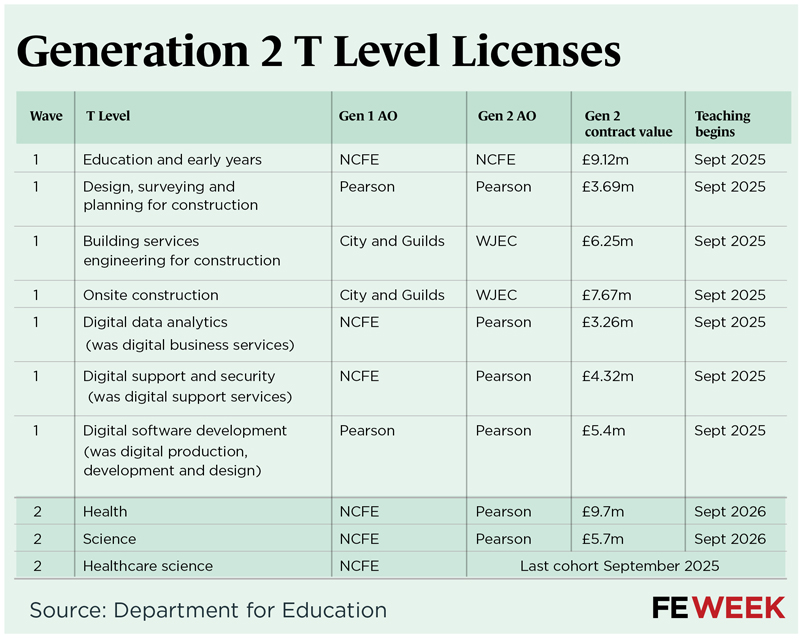

It comes as the Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education today confirmed that the healthcare science T Level will be scrapped from 2026-27 and will consolidate the content within the wider health and science route. The DfE has also scrapped plans to launch T Levels in beauty and catering.

Rob Nitsch, chief executive of the Federation of Awarding Bodies, said: “We’re seeing an improvement, which is encouraging but it’s not the exponential increase needed for T Levels to become the dominant technical offer.”

Earlier this week, the independent curriculum and assessment review, led by Becky Francis, highlighted that, using 2023 data, just 2 per cent of 16 and 17 year olds took T Levels.

Catherine Sezen, director of education policy at the Association of Colleges, said: “While there has been a steady increase in enrolments over the past five years, the numbers have not fully met the government’s initial expectations.”

This is the first year that DfE has provided a breakdown of T Level starts by the 21 individual pathways rather than route.

Of the T Levels debuting this academic year, the animal care and management pathway was the most popular with 1,281 starts. Craft and design, a new part of the creative and design route, only garnered 136 starts.

Meanwhile, the new media, broadcast and production T Level has 600 starts.

Nearly 5,000 learners onboarded onto the education and early years T Level in September, the largest cohort this academic year followed by 3,772 learners on the health T Level and 2,054 digital production, design and development.

Students opting for the health and science route has grown since it was offered in 2021-22, when 1,600 learners started on the health and science route, increasing to 2,819 last year. Overall, there were 4,273 entries on the route this year.

DfE will also be making changes to the content and assessment of the digital, construction and education & early years T Level routes, including streamlining the core content and getting rid some the amount of assessments in specific T Levels.

Sezen said there are two key barriers to T Level uptake: “Accessibility, due to overlapping content and extensive assessments, and placement capacity. The introduction of Generation 2 T Levels in 2025 aims to address the first challenge by streamlining content and reducing the volume of assessments.

“Placements provide invaluable experience for students. While recent changes have been helpful, we have been consistently asking for a clear plan to get more employers involved in all types of programmes to ensure there are enough placements available.”

Today’s data also shows take up of the T Level foundation year rose by a third from 6,900 to 9,228 learners this year studying at 162 providers.

This is the first year of the name rebrand for the qualification; it was previously called the T Level transition programme.

The most popular was the health and science foundation course, with 2,133 starts. The lowest take up was the legal, finance and accounting, which attracted just 25 students.

DfE declined to comment.