Martin Dunford, chair and a co-founder of the Association of Employment and Learning Providers, is retiring from the role. He reflects on the many policy shifts AELP has achieved over the years

“So one day I got this fax through. It was a fax to the ten largest training providers to say, ‘Why don’t we have a meeting?’ – and it was because none of us knew anything about each other.”

Martin Dunford is stepping down after an astonishing 18 years as the chair of the Association of Employment and Learning Providers (AELP), which represents independent apprenticeship and work-based training providers in further education.

If some of the public – and many ministers – can be hazy about what colleges offer (if they’ve gone through the schools system), then it’s fair to say independent training providers are even more of a mystery to many outside FE. AELP has spent two decades trying to change that.

And with Dunford as chair since 2004, it’s little wonder AELP’s leaders said his departure this week marks “the end of an era”.

Dunford explains that back in about 2000, when he got that fax through, staff in the different providers never met up, let alone had any profile outside the sector.

The fax was from John Hyde, then chief executive of Hospitality Plus, a hospitality and catering training provider (he’s now chair at HIT Training).

“So we went along to this meeting, and we said, ‘What do you do, that’s interesting, this is what I do,” Dunford smiles.

Others in attendance included Stewart Segal, chief executive of Spring Skills, the largest training provider in sectors such as retail and customer services, and Hugh Pitman, who founded vocational and employment training provider JHP Group.

This tentatively interested group then got in touch with another organisation already in existence, the National Training Foundation, run by Neil Bates, who is now chair of The Edge Foundation, and the late Frank McMahon, managing director of YH Training, who would later become AELP’s treasurer.

“We met up with them, and we said, why don’t we create something?” says Dunford. It worked: AELP was launched in 2002.

“We all put some money in to get it going. We started with nothing, no staff, no money, one chief executive and a handful of members.”

We all met up and we said, ‘Why don’t we create something?’

Dunford had been invited to the table because he was managing director of The Training and Business Group, a role he got at just 38 years old in 1995.

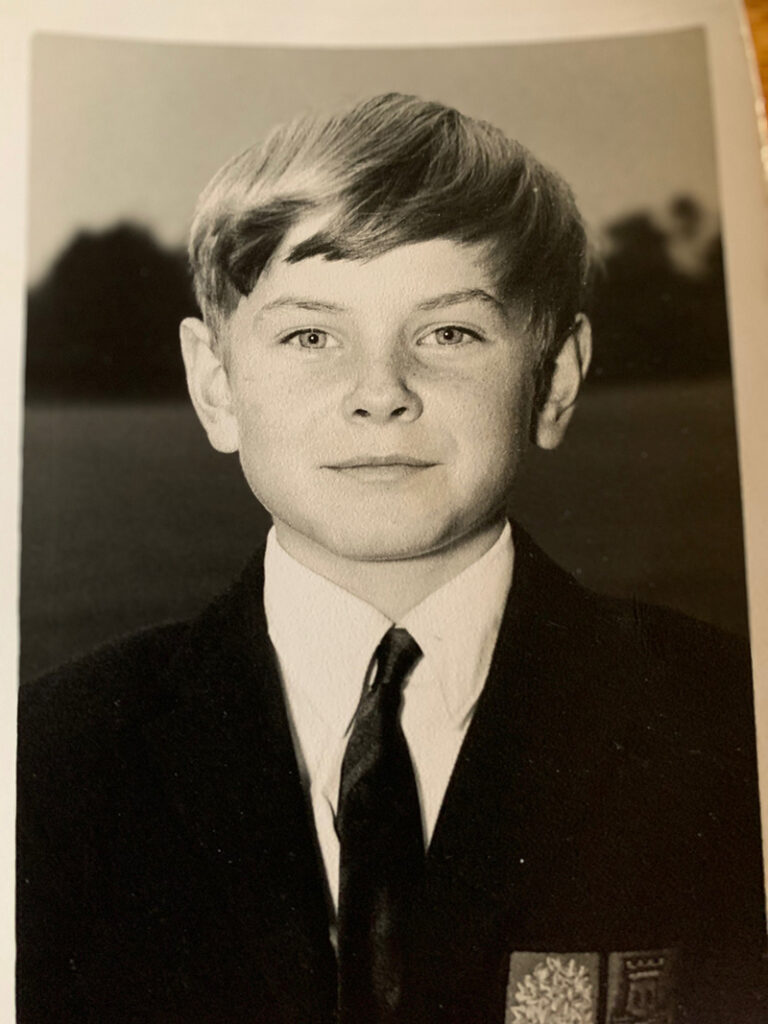

He’d grown up on the Wood Farm housing estate, based around factory work in Oxfordshire, and had always set his sights high.

“Everyone who lived on these estates worked at the factories – most of our dads worked there,” says Dunford.

Another child on the same estate as Dunford is a familiar name: Frances O’Grady, now general secretary of the Trades Union Congress.

She attended the local girls’ grammar, just as Dunford went to the boys’ grammar, but they only realised the connection in their backgrounds later on as their profiles increased. Going to grammar school with “Oxford dons’ sons” gave him confidence, but Dunford is clear: “That system is unfair.”

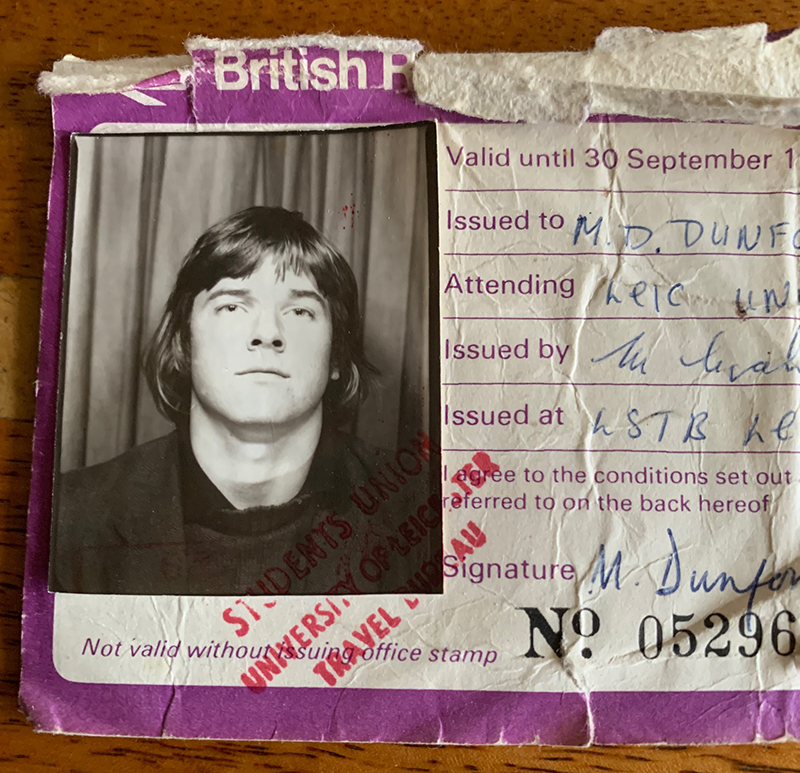

After school, he studied a biological sciences degree at Leicester University, before taking up a teaching job at a “crammer” – a private A-levels college in Oxford. But he wanted to go to London to try to become a general manager or a CEO.

He recalls meeting business leaders later on in life, when studying an MBA at Hendon Business School at Middlesex University. “I’d be meeting the MD of BP, or Saatchi, and you just realise, everyone is the same. It’s just what you want to achieve.”

First off, he took a job selling high-end technology to the pharmaceutical sector in the UK, becoming field sales manager by age 27. He was headhunted to join a biotechnology start-up called Oros Instruments.

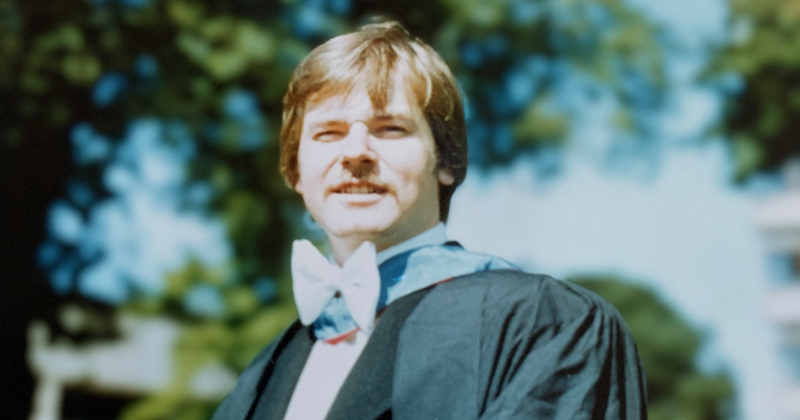

Not long after that he studied his MBA and applied for a general manager advert in the Sunday Times at Training Business Ltd. He became managing director, and changed the name. He’d entered FE, and was here to stay.

AELP’s very first chief executive for a decade was Graham Hoyle, who had been on the Gloucestershire training and enterprise council – one of the 72 councils introduced under the Thatcher government. Dunford’s company worked closely with it to deliver provision.

“Graham had been in the civil service, and so he did a great job of getting us on the map. What you have to understand is we didn’t know who each other were!”

As the word got out, to Dunford’s surprise about 40 colleges with their own ITPs as separate companies quickly joined as members.

It was unexpected as they already belonged to the Association of Colleges. “They weren’t anti-AoC but they clearly did think there was a gap.”

This touches on a tension in the early years of AELP, nods Dunford. “It was fairly adversarial with AoC in those days. Or they just ignored us.” He grins, adding: “There’s good co-operation there now.”

Under Dunford, AELP has recruited its chief executives from both ITPs and colleges, with Stewart Segal following Hoyle, then Mark Dawe, who was a college principal and former senior civil servant at the Department for Education.

AELP’s current chief executive, Jane Hickie, is from a training company background and was AELP’s former chief operating officer.

The most “forward-thinking colleges” tend to work closely with AELP, notes Dunford.

Dunford felt it was occasionally a struggle to make the voice of ITPs heard. “It’s changed now, but it was so different back then,” he says.

The attitude towards work-based learning and apprenticeships verged on snobbish sometimes.

Dunford recalls being in a meeting with Charles Clarke and suggesting that the New Labour education secretary get an apprentice.

“You should have seen the jaws drop on the civil servants in the room. I’m not saying they’re all Oxbridge, but there was a whiff of that.”

So AELP began lobbying ̶ and if there is one thing Dunford is proud to leave behind him, it’s a legacy of doing so effectively.

He remembers telling it straight to then-prime minister Tony Blair during a reception at Number 10.

“I said, ‘Your policy is great, but your implementation is achingly slow.’ So he called over his education special adviser and the next day, we were having a meeting with him.

“They learned a lot through engaging with us about what was going on on the ground,” he adds. “They’d say, ‘We love meeting with you, because you tell us what’s going on in our agencies!’”

The upshot of engaging closely with government is “we regularly deliver small, incremental policy wins”.

One example is traineeships, says Dunford. “We lobbied and persuaded the government to introduce traineeships.

We didn’t give it that title but that’s what we were recommending.” Dunford’s current company, where he is chief executive, Skills Training UK, delivers traineeships now (he moved over in 2008), and overall, 56 per cent of traineeships are now delivered by ITPs.

“A lot of people box ITPs as apprenticeship providers, but traineeships are largely delivered by us, and we do BTECs through study programmes.”

He adds that Nadhim Zahawi, the relatively new education secretary, is “also encouraging a wider supply of T Levels”, and Dunford thinks “there will be more ITPs [doing T Levels] in future”.

Other areas where AELP have met with lobbying success is the apprenticeship levy, he says. “We didn’t argue for the levy, but for years, we argued for a demand-led system, rather than a contract-led system.”

For years, we argued for a demand-led system, rather than a contract-led system

Another example is prison apprenticeships. “We’ve been lobbying on that, along with other people, since 2016.”

Not quite achieved yet is individual learner accounts. “A really good system of choice, that could include individual skills accounts, with Ofsted-accredited training providers.”

(When they were last introduced in the early 2000s, fraudulent abuse caused them to be ended after just one year). “That’s something we know we’re not going to win in the short term. But we’ll keep lobbying.”

Dunford sums up his view: “It should all be based on who can produce the results.”

Yet there’s still a tendency for ministers, however friendly towards AELP, to slip into the assumption that colleges should be the go-to providers, says Dunford.

He says he can recall former skills minister Nick Boles, whom he respected, “doing a speech at AoC in which he basically said, ‘Don’t let these guys steal your lunch’”, referring to ITPs.

Zahawi, whom again, Dunford is pleased to have in post, has also called for colleges to be doing a larger proportion of apprenticeships.

“And you have to think, well, why? I don’t think it’s necessarily anti-ITP – it’s a clumsy way of encouraging colleges to be more employer-focused.”

But Dunford is clear: ministers should look at what’s working.

“If that’s a college, absolutely fine. If it’s a group of ITPs, they should be encouraging that.”

AELP is continuing to make its case. Just last week, it published a report called Excellence for Learners, Value for Employers: How independent training providers can deliver the workforce of the future.

It points out the 1,200 ITPs are “the most common type of post-16 provider” in the country; that 80 per cent are judged grade 1 or 2 by Ofsted; and more than 50 per cent of all learners who got their functional skills level 2 qualifications in 2019-20 did so with an ITP.

Succeeding Dunford as chair is Nichola Hay: “Nicki is forward-thinking and strong,” grins Dunford. “I’m delighted she’s got the gig.”

He reflects on where AELP has got to under his chairmanship.

“There’s now a decent balance sheet and over 800 members. People assume we’ve been there for ever. But we started from nothing.”

Your thoughts