Jeff Greenidge tells Jess Staufenberg why encouraging non-racists to be more vocal about their opposition to racism is the crucial next step for the sector

Just over a year ago, the first ever “director for diversity” was appointed by the Association of Colleges and the Education and Training Foundation – Jeff Greenidge.

The former languages school teacher and director with training provider Learndirect had landed a year’s contract with both organisations: a seemingly huge title and huge job.

The scale of the challenge was, and is, vast. Of the 239 general FE colleges in England, it was estimated in 2020 that between only 12 and 14 were led by principals from black, Asian and ethnic minority backgrounds, according to the Association of Colleges.

Even more concerningly, that marked a drop from 13 per cent in 2017 to around six per cent – prompting national newspaper coverage about “systemic racism in the sector”.

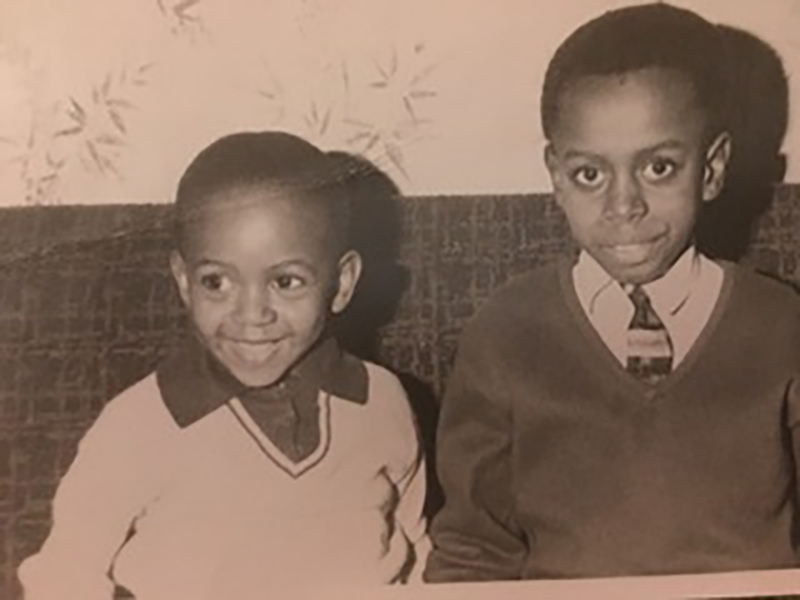

So it’s perhaps unsurprising that AoC asked Greenidge to stay on an extra six months, until July (he has finished his work with ETF). But Greenidge, who was born in Barbados and came to the UK aged five, is clear that keeping him in post doesn’t mean he’s the one driving change from above.

“When you have someone who has the post of director for diversity, it’s easy to shift responsibility to that person,” he explains.

“So this post is about a stimulus. That’s what I was doing last year – looking at those game-changers, those people who have taken up the mantle and decided to take action.”

This next six months is about supporting those people to bring about further concrete change, according to Greenidge. “There are some things almost at the tipping point, and it’s about getting them over that tipping point.”

Being almost at a “tipping point” sounds to me like progress is still too slow, but Greenidge has a way of talking positively, without sounding contented, about everything brilliant happening that’s not always apparent on the surface.

More change is happening around race, and inclusion more widely, in FE than is often publicly known, he says.

“You’d be surprised how many people there are in FE doing that quietly and unobtrusively, but who are taking action,” he nods.

There are three main strands to his work: practitioners, principals and sector organisations. Three years ago, Greenidge set up a coaching programme for senior leaders, middle managers and governors in FE with a protected characteristic background (including race, sex, sexuality, disability, gender reassignment and age).

The programme, which delivers seven hours of coaching to between 20 and 30 people a year over three months, has continued to grow with Greenidge’s move to the ETF and AoC, finding and developing more “change-makers”.

The programme has a two-fold purpose: the first is to “help individuals gain insight into their strengths, the things that hold them back, the habits that sabotage them”, so they can progress into leadership roles.

The second is for individuals to “pay back” the beneficial experience of coaching by taking action in their own contexts, explains Greenidge.

We start with the first: building confidence and risk-taking abilities. Greenidge tells me with a smile that he sabotages himself by “eating ice cream”. Later, and more seriously, he says he realised he was biased towards recruiting people with the same interest in sport that he has.

“If someone mentioned in an interview that they played sport, my ears would prick up. I had to stop that, because that was a bias I had,” he notes, eyebrows raised.

For other people, self-sabotage can be about being far too comfortable. “There could be an individual who has been in a job for a number of years, they live five minutes from work, and they don’t know how to progress in their role because they don’t want to move away from college,” he narrates.

“They’re sabotaging themselves because they’re in that comfortable chair, and it’s hard to get out of that comfortable chair.”

Good coaching can result in people changing their jobs, even getting a divorce, Greenidge continues. “Slowly the person becomes comfortable with being uncomfortable.”

Once people feel more confident about their ability to make changes, they are encouraged to take action around equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI), says Greenidge. Here, his precision with language (he has a degree in French and Latin) brings refreshing clarity to the term.

“Equity is a measure of justice and fairness, so perhaps that’s about bringing in a black curriculum. Diversity is a quantitative measure of representation, so, perhaps we need to understand what the diversity pay gap is.

And inclusion, that might show you that half the staff feel like they don’t belong. It’s about breaking down EDI into its constituent parts, so you can begin to take action.”

It is these concrete actions that Greenidge is helping to “tip over” into long-term change over the coming months.

Someone who has already made waves is Ellisha Soanes, EDI coordinator at West Suffolk College. She has pulled together a curriculum in which students research black and other minority histories in their local area of Suffolk, explains Greenidge.

Curriculum is particularly important to Greenidge: he remembers the impression it made on him to learn about wealthy black emperors in the Roman Empire, because he studied Latin at school.

“Otherwise, youngsters grow up thinking black history is all about slavery and deprivation.”

In another example, a member of staff at Manchester College has now initiated a staff-to-staff coaching programme across the organisation, inspired by Greenidge’s coaching programme.

Inclusion might show you that half the staff feel like they don’t belong

Meanwhile, someone at a college north of London “began to challenge the senior leadership about their way of thinking about EDI”, in particular around digging more deeply into student ethnicity data to help close attainment gaps.

“The twist in the coaching programme is it urges the individual to take some action – that you’re not just being coached for your own benefit,” says Greenidge.

This work with practitioners is backed up with networking opportunities for principals, he continues.

“If they’re nervous, how can we support principals and leaders who have already made a commitment to these EDI strategies?”

There are about 12 principals involved at present, with Ali Hadawi, principal at Central Bedfordshire College, a critical driving force for this work.

Principals have one-to-ones about change strategies and also regular meet-ups every two to three months. They’ve met with David Hughes at AoC, David Russell at ETF, and next in Greenidge’s sights is Shelagh Legrave, FE commissioner, who is apparently enthusiastic.

Greenidge adds: “This is about a safe space in which to have uncomfortable conversations.”

The third strand is again a drive to turn principles into sustained action. WorldSkills UK, ETF, AoC and the Federation of Awarding Bodies have all made commitments to equity, diversity and inclusion – now the job is to check those organisations make a difference, says Greenidge.

“How can we convince them to show the progress they’re making? Because if they’re not showcasing it, we know it’s not being made.”

But again, Greenidge comes back to the need for ordinary staff members to speak up. He is encouraging and coaching people – but it is their voices that can make the long-lasting difference.

“There is still a problem,” he responds, when I ask about the state of racism in FE now. “Clearly there are people who are racist. I personally don’t believe everyone is racist. What I want to do is pull together those people who are quiet and non-racist, and get them to be a bit more vocal about their non-racism.”

It’s the same with homophobia or misogyny, he continues. “I would like to give those people who are pro-inclusion and pro-diversity the confidence and belief to be more vocal about those things. If you challenge a bully, the bully will back off.”

What about ignorant statements, or “clumsiness” of language, rather than bullying? I ask. Greenidge answers with the wisdom of a coach.

You “can’t tell” people exactly what they should be saying, he says. “But if you repeat back to them what they’re saying, they will hear themselves. They might slowly start to have the insight that they need to question themselves.”

This preference for bridge-building (bar confronting bullies) is at the heart of Greenidge’s approach.

As we conclude, he gives a word of warning about the approach he believes fits the UK context best.

This is about a safe space in which to have uncomfortable conversations

“We tend to follow the American, very confrontational model in the way we approach things,” he says. “America is a very segregated society along racial lines. But here in the UK, people are becoming more and more mixed.

“It’s harder and harder to find out if someone is Asian, Greek, mixed race or Iraqi. In my view we don’t have a system here based on racism. The split with us is more around deprivation, about the haves and have-nots.”

This means the UK has more opportunity than the US to act as a collective to improve equity, diversity and inclusion, notes Greenidge.

“We have an opportunity in the UK to say, what are we going to do to make our country more inclusive? And that starts with, what am I going to do to make my college more inclusive?”

The time is now, he concludes. “The grandchildren of the Windrush generation are coming to the fore.”

Your thoughts