FE Week takes a look at how prison education has adapted after face-to-face teaching was suspended following the Covid-19 outbreak

Formal prison education was largely suspended almost four months ago as part of a wider national jail lockdown to reduce the risk of coronavirus transmission.

Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) advised the Justice Select Committee on March 24 that it was moving to an “exceptional delivery model” and confirmed that non-essential activities should be stopped.

Since then, inmates, who usually spend at least ten hours a day outside their cells, with many using that time to study with tutors from colleges and training providers, have been in lockdown for up to 23 hours a day.

Latest HMPPS data shows there have been a total of 44 deaths among prison service users where Covid-19 is suspected to be the cause and 510 prisoners have tested positive so far, according to the Ministry of Justice. In addition, the Scottish Prison Service College in Falkirk was closed at the end of April after a suspected outbreak of coronavirus among its trainers.

As a result of safety concerns, colleges and training providers have taken different approaches to overcome the challenges posed by the current restrictions in order to continue providing some form of education to their learners in jail.

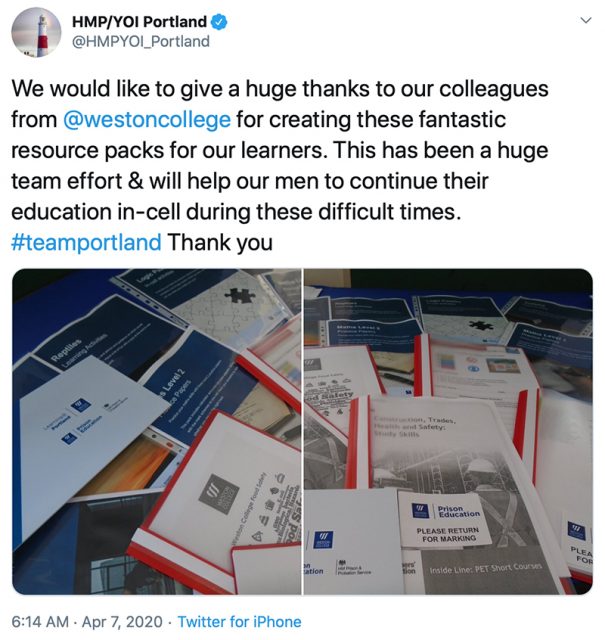

Weston College, in Weston-super-Mare, which is one of four providers of the Prison Education Framework, has been printing 150 different learning packs every week and distributing them to the 19 prisons they serve on a bespoke basis.

These include packs tailored towards English and maths assessments for GCSE and functional skills as well as technical and vocational qualifications.

Andrea Greer, deputy principal of prison education, HR and reputation at Weston College, told FE Week they had to “mobilise the distance learning materials and remote learning materials incredibly quickly” during this “unprecedented time” because there was “obviously a need to try and keep up as much momentum as possible”.

She said Weston College has been trying to ensure the programmes are delivered sequentially where possible, while staff have been marking work and offering feedback to individual learners. They had also distributed books to residential units before prison libraries were locked down to ensure reading material was available.

Although the service has received “really, really positive feedback” from prisoners about the learning packs, Greer admitted that the discontinuation of face-to-face education will “disrupt continuity and focus”. She said that some learners may find it difficult to adapt to in-cell learning or find that noise or other distractions on residential units impedes their studying. The deputy principal was also concerned about the effect of confinement, a lack of visitors and anxiety about the pandemic on participation.

The provision offered by the providers of the Prison Education Framework usually includes a core curriculum of English, maths, ICT and English for Speakers of Other Languages.

It varied across prisons pre-lockdown as the numbers of hours of education to be offered are not stipulated in the contracts but can reach up to five to six hours a day.

Prison governors have the autonomy to decide about other services that will make up their education offer and therefore the amount of face-to-face teaching available is dependent on individual prisons.

At HMP Coldingley, in Surrey, for example (a prison where Weston College teaches), prisoners can opt for six weekly hours of education, in which they are able to type up assignments or access the virtual campus.

This hosts resources such as the Open University’s virtual learning environment.

Further disruption will be experienced by prisoners who may not be able to complete qualifications if they are transferred or released before delivery resumes. Moreover, newly arriving prisoners will not be able to access the full induction programme about their learning and training options.

However, Greer understands that some prisoners who had completed or almost completed learning may receive calculated grades, similar to this year’s cohort of students at other FE providers. She said: “As per Ofqual guidelines there are likely to be some claims for expected grades, especially for functional skills, provided that there is evidence of learning progress and performance plus assessments indicating that learners were on track to pass examinations.”

Another prison education provider Novus, which is part of the LTE Group, has used in-cell television, prison radio, telephony and digital resources to “support, engage with and educate” their learners in addition to distributed physical learning packs.

A spokesperson said: “Current restrictions have meant we’ve not been able to have the same face-to-face contact with our learners so we have had to adapt our delivery to address the challenges of the current situation.”

It has also worked with partners such as Koestler Arts, Music in Prisons, Sing Inside and White Water Writers to develop “adaptive offers that bring the classroom to the cell”.

Sarah Hartley, operational lead for creative arts, enrichment and families at Novus, added: “Access to, and engaging with, the creative arts is something that can be hugely beneficial when prisoners are confined to their cells and in isolation. Creative activities are integral to the opportunities that we are producing across Novus to engage with our learners from afar.”

Learners in all Novus establishments have been invited to participate in a project with Tate Modern called “A Future I Can Love”. Their in-cell brief is to respond to the pandemic through sketches, written word, poetry and music.

All four Prison Education Framework providers, which also include Milton Keynes College and independent learning provider PeoplePlus, are having twice weekly meetings with the MoJ, HMPPS and awarding organisations to share best practice, and Weston College’s learning packs have been uploaded to a shared portal so they can be accessed by other educators.

Greer said: “I think that there was a concerted effort on the part of all providers to work together for the benefit of those learners. It’s quite an open forum… that’s worked really well over this lockdown period.”

In contrast, one young offender institution has been delivering two hours of socially distanced face-to face education every weekday throughout lockdown, according to HM Chief Inspector of Prisons, who conducted scrutiny visits in April.

The young people, aged between 15 and 18, have been able to keep two metres apart at Parc, in South Wales, which is run by security company G4S. This has included classroom-based pathways as well as carpentry, cookery and PE. They additionally receive in-cell workbooks and library provision through a delivery service.

Furthermore, online in-cell teaching has been taking place in some institutions but is similarly not widespread due to limited access to remote learning platforms.

The Prisoners’ Education Trust (PET), which provides educational materials to people in prison, has also been working with staff to continue delivering distance learning courses during this time. The charity is calling for all prisoners to have restricted in-cell access to a computer device and an intranet where they can access interactive educational resources.

Francesca Cooney, head of policy, said: “It would completely revolutionise education provision and this Covid crisis has really highlighted the digital divide between people in the community and prisoners.”

She added that enabling prisoners to progress in individualised courses and to complete assessments “would have made all the difference in lockdown” and is “necessary if education in prisons is going to be relevant”.

Cooney believes prison education is vital as it can give inmates “good outcomes”, which helps them succeed when they are released.

The MoJ’s data lab found that ex-prisoners who had completed education courses during their time in jail – which include GCSEs, A-levels and level 1-3 diplomas – were 25 per cent less likely to reoffend, and 26 per cent more likely to find employment in their first year of release.

In addition, the department has reported that participation in prison education carries a net benefit of approximately £5,400 to £5,600 per learner.

A conditional roadmap on the easing of lockdown in prisons, published by the government in June, set out that when education activities do resume, they will do so with “considerable restrictions and adaptations”, including reduced capacity, and progress will be “slow and incremental”.

Although the average number of course applications received by the PET per month has dropped significantly from 220 to between 40 and 50 over May and June, the charity predicts a rise in engagement once prisoners are able to access education departments.

Cooney added: “I think they’ll be really looking forward to having the opportunity again. [But] even when education comes back in on the ground in prisons, that will be socially distanced education initially, so far fewer people will be able to do it than were doing it before, and there were never enough spaces in the first place for people.”

A government prison service spokesperson said: “Restrictions on daily life in our prisons have helped save lives and protect the NHS.

“Workbooks and in-cell activities have been provided and services will return to normal when it is safe to do so.”

Your thoughts