Although seen by some as controversial, degree apprenticeships are central to the government’s plans to put technical education on a par with academic education. The Department for Education has repeatedly referred to the number of Russell Group universities signed up to the register of apprenticeship training providers as a sign that it’s succeeding in this regard. But are they actually delivering apprenticeships? FE Week spoke to some of them to find out.

When the University of Cambridge secured a place on the register of apprenticeship training providers in February this year, the mainstream press finally took notice – with both the BBC and The Times reporting that the university was set to offer apprenticeship training.

But while those plans have yet to come to fruition, earning while you learn is an option at an increasing number of Cambridge’s fellow Russell Group universities.

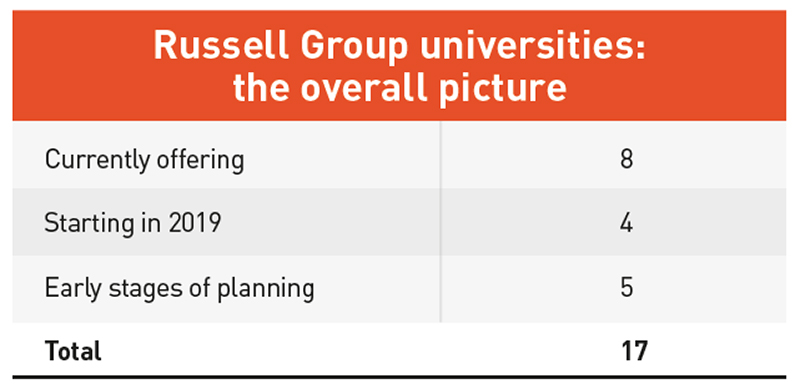

Of the 17 on the Education and Skills Funding Agency’s register, eight are already running at least one programme.

A further four are set to introduce degree-level apprenticeships in 2019, and the remaining five are in the early stages of development.

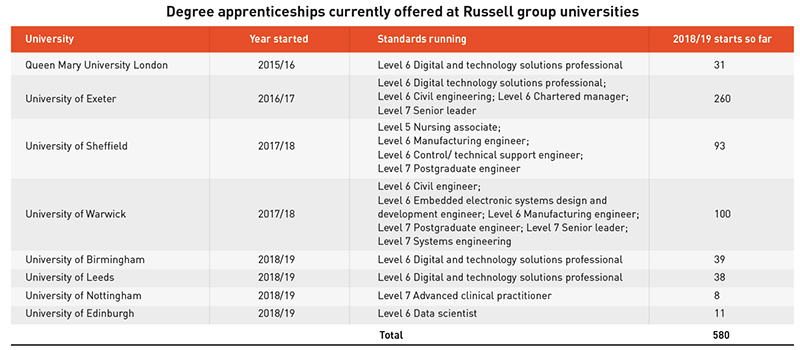

Numbers are low at the moment – the eight have combined starts of around 500 so far in 2018/19. In comparison, there were more than 8,000 starts on level six and seven standards across all institutions in the first nine months of 2017/18.

But these are set to increase, with all the universities FE Week spoke to planning to expand their offer in the years to come.

“Those with no plans must stop dragging their feet”

Former skills minister and now chair of the education select committee Robert Halfon has long championed degree apprenticeships, calling them “a crucial step on the road to delivering social justice and boosting Britain’s productivity”.

He told FE Week it was “encouraging” to hear the findings of our investigation, but said all 17 universities “need to redouble their efforts to open up more of these opportunities, including to the most disadvantaged”.

Mr Halfon also urged the government and the IfA to do more to encourage universities to offer degree apprenticeships.

“Those with no plans, such as Oxford, must stop dragging their feet and get on with providing degree apprenticeships which can do so much to help people to climb the ladder of opportunity,” he said.

“We were best placed to address skills shortages”

Queen Mary University London was the first Russell Group university to offer degree apprenticeships in 2015.

The university “jumped in” with the level six digital and technology solutions professional standard, according to Jamie Hilder, the university’s degree apprenticeships manager.

“We’ve already got a dialogue with employers in those sectors and identified a skills need, so our rich experience in the field and ideal location can help them address those skills shortages,” Mr Hilder said.

Many of the newer programmes are prompted by the introduction of the apprenticeship levy.

Three of the four new degree apprenticeship programmes being launched by Russell Group universities this academic year are run in partnership with professional services firm PwC.

All three are in digital and technology – areas where the firm had identified as having a skills gap, according to Louise Farrar, PwC’s head of student recruitment.

It makes more economic sense for companies to use their levy than to be paying out of their HR budget

“We’ve got a great opportunity with our levy money. Wouldn’t it be great if we can use that money to direct into areas where we need to build to meet future skills gaps?” she said.

The University of York is one of the universities planning to enter the degree apprenticeships market in 2019.

The university already works with local employers to offer part-time master’s degrees for people in work, and so its level seven apprenticeships will be an “extension” to that, according to Amanda Selvaratnam, the university’s head of enterprise services.

“For many companies, it makes more economic sense for companies to use their levy for that sort of provision than to be paying out of their HR budget,” she said.

“You’ve got to be on your toes”

Developing a degree apprenticeship programme requires much greater collaboration between universities and employers than a traditional degree.

But for many of the universities FE Week spoke to, this hasn’t proved to be the greatest challenge.

The University of Nottingham, which is starting to offer the level seven advanced clinical practitioner standard this year, said “administrative complexities” were the biggest hurdle to overcome, “particularly meshing the sorts of reporting that is going to be required into current university systems”.

A number said they were having to change their ways of working – from recruiting students to how lectures are delivered.

The “vocational bent” of the programmes at Queen Mary meant they were placing more weight on “professional experience, maturity and application of knowledge to real-life scenarios” than purely academic achievements, Mr Hilder said.

Professor Tim Quine, deputy vice-chancellor for education at the University of Exeter, said it had “sought to innovate around delivery models” for its degree apprenticeships, using “blended and e-learning, reflective practice and block residentials”.

“All of this has taken time to understand and develop, and investment to support,” he said.

Some of the challenges faced by the universities will be familiar to many providers already delivering apprenticeships, with a number complaining about the non-levy procurement process, the Institute for Apprenticeships’ “aggressive funding policy” and the constant “iterations and revisions” to standards.

But while the FE sector is used to dealing with these difficulties, universities “traditionally haven’t been as adaptable”, said Louise Cowling, head of degree apprenticeships at the Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre at the University of Sheffield.

The university began offering degree apprenticeships in manufacturing and engineering in 2017/18, and has just started offering level five nursing associate courses in 2018/19.

“You’ve got to be on your toes. I think universities are learning that they need to respond much quickly than they have done in the past,” she said.

“Employers want a strong technical degree”

All of the universities FE Week spoke to were keen to stress that their degree apprenticeships had the same level of academic rigour as their traditional degree programmes.

Prof Quine said that Exeter’s degree apprenticeships allowed it to “extend the high-quality educational experience that we pride ourselves on” to “talented individuals” who’ve chosen not to study for a full-time on-campus degree.

And Ms Farrar said that the chance to study for a “top degree at a great institution” was one of the attractions of PwC’s programmes.

Employers also appear to appreciate the calibre of learning on offer from these institutions.

Mr Hilder said that “anecdotally we’ve been told that the depth of the course is different” at Queen Mary, with employers rating it “more substantial” than other degree apprenticeship programmes.

Being a “research-focused university” was seen as one of Sheffield’s strengths, Ms Cowling said.

Employers have come to us and said they want a strong technical degree

“Employers have come to us and said they want a strong technical degree, using modern technology”, she said.

Students on the AMRC’s programmes are able to draw on the centre’s research, and then apply that to their work environment.

“We’ve had students who’ve worked for large employers, and the students have been able to recommend changes to manufacturing processes and procedures within their organisation,” she said.

“Degree apprentices are better in terms of diversity”

While full social demographic data on the new degree apprentices isn’t yet available, there are already signs that they’re widening participation.

While the average proportion of women on tech degrees is around 16 per cent nationally, PwC has “recruited 30 per cent”, Ms Farrar said. “We’re really pleased with that one.”

Likewise, Queen Mary’s cohort of degree apprentices are “better in terms of diversity” than its other undergraduate students – thanks in large part to the university “going into areas of high deprivation and low rates of participation in higher education, people who don’t typically apply to university, and saying ‘do you know degree apprenticeships are an option?” Mr Hilder said.

Oxbridge degree apprenticeships – will they ever happen?

Being able to ‘earn while you learn’ at Cambridge or Oxford is seen by some as the pinnacle of parity of esteem between vocational and academic education.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t look likely to happen anytime soon – at least not at undergraduate level.

Cambridge successfully applied to be on the register of apprenticeship training providers earlier this year, and said at the time it planned to focus its initial offer at postgraduate level through its Institute of Continuing Education.

A spokesperson told FE Week that planning was still underway, with the aim of introducing the first programmes in 2019 at the earliest.

A “number of interested parties internally” are in discussions with the ICE about mapping “already established courses into apprenticeships”, he said.

Meanwhile, a spokesperson for the University of Oxford said it currently did not “have any plans to offer degree or degree-level apprenticeships”.

Degree apprenticeships – the wider picture

The first degree apprenticeships were launched in 2015, with the aim of offering students the chance to study for a degree while working as an apprentice.

Just a few institutions were on board at the start, including Queen Mary University London, Sheffield Hallam University and Manchester Metropolitan University.

Fast forward three years and there are now 111 universities or university colleges on the register of apprenticeship training providers, although not all of them will be offering degree apprenticeship programmes.

According to the latest available Department for Education figures, there were 8,560 starts on level six or seven apprenticeships, which correspond to degree and master’s apprenticeships, in the first nine months of 2017/18.

Many of these starts are likely to have been at modern universities or colleges offering degree-level provision, many of which received funding through the Degree Apprenticeships Development Fund to establish their programmes.

A total of £10 million was on offer from the fund, which was managed by the now-defunct Higher Education Funding Council for England.

It was awarded in two phases, with 25 HE institutes and 20 colleges receiving a combined total of £4.5 million for 18 projects in the first phase, announced in November 2016.

A further 27 projects, involving around 60 universities and colleges, received £4.9 million between then in the second phase, announced October 2017.

Between them they were expected to result in nearly 10,000 new apprenticeship opportunities by this September.

Your thoughts