None of England’s young offender institutions provided children in their care with the education they were entitled to during the last three years, an FE Week probe has revealed.

For the first time, figures released to FE Week by the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) list how many hours of education young offenders received under the current batch of education contracts.

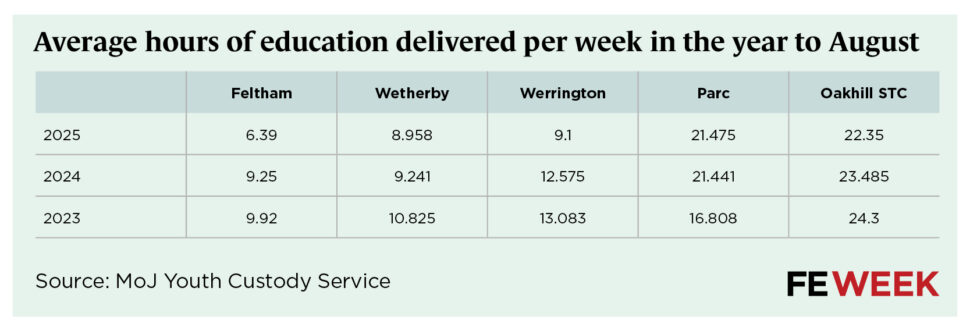

The data shows all three YOIs failed to hit the 15 hours per week tuition level agreed since October 2022, a month after the contracts started.

The worst YOI was Feltham, where contracted provider Shaw Trust delivered an average of 6.4 hours of education per week in the year to August 2025 – missing the MoJ’s benchmark by over eight hours.

England’s other two YOIs, Wetherby and Werrington, also delivered less education than required every month since October 2022, with the year to August 2025 being the worst so far.

YOIs are legally required to provide young people of a compulsory school age – about three quarters of their population – with at least 15 hours of education each week.

But staff shortages and high levels of violence have increased the time young offenders spend in their cells.

A series of reports sounded the alarm about youth custody in the last year, with one from the Commons’ Justice Committee last week describing conditions as “deplorable” and the lack of access to education “shameful”.

Helen Dyson, interim chief executive at social justice charity Nacro, said: “It is unacceptable that not a single young offender institution is meeting the basic 15-hour weekly education requirement.

“Young people in custody are being denied the education they are entitled to – left in cells for up to 22 hours a day with little or no learning.

“Education is a lifeline, not a luxury. Without it, rehabilitation is undermined, and the cycle of reoffending is reinforced.”

Learning hours lost

FE Week asked the MoJ for the education delivery statistics through a freedom of information request after noting it failed to include them in its regular youth custody data releases.

Officials shared figures that revealed education delivered at Feltham, Werrington and Wetherby averaged between 6.4 and 9.1 hours per week in the year to August 2025, a decline of up to 36 per cent since 2023.

It suggests that the average child in youth custody misses out on seven hours of education per week, or 266 hours per year based on the 38-week school year.

And it undermines claims made on the YOIs’ websites, where Werrington promises “30 hours of education per week” and Wetherby commits to 21 hours.

Feltham, described as “bleak” and “troubled” in a recent HMI Prisons inspection report, does not say how many hours it aims to provide on its website.

Education is provided by Shaw Trust at Feltham, PeoplePlus at Werrington, and LTE Group, trading as Novus, at Wetherby. The contracts are each worth between £2 million and £3.8 million per year.

None of the education providers commented when contacted by FE Week.

A spokesperson for the Youth Custody Service, part of the Ministry of Justice, said an “improvement plan” had been launched to increase levels of education, but was unable to provide further details.

They added: “Many children entering custody have already been excluded from mainstream education and arrive with complex needs.

“The overall number of children in custody has reduced and those that remain often require support before they re-enter formal education, to ensure they are ready to engage and learn.”

Better in Wales

The only UK YOI to deliver more than the minimum 15 hours was Parc, in Bridgend, South Wales.

It delivered an average of 21.4 hours per week through provider Novus Gower, a joint venture between LTE Group and Gower College Swansea.

Parc housed only 26 children at its most recent inspection.

Privatised Oakhill Secure Training Centre (STC) in Milton Keynes, which cares for up to 80 children aged 12 to 17 who are too vulnerable for a YOI, delivered an average of 22.4 hours per week, missing its 25-hour contracted target.

The STC’s contractor G4S said refusals to attend, ill health and court appearances had pulled its average down.

Oakhill STC is currently subject to a major safeguarding review over concerns about safety and staff conduct raised earlier this year.

An Ofsted monitoring visit of the centre in October found staffing levels in education remained “too low”, resulting in a less “varied and interesting” curriculum and unmet needs for children with special needs.

Outsourcing model criticised

Both the Prison Governors’ Association (PGA) and Prison Officers Association (POA), a union representing rank-and-file officers, criticised the MoJ’s outsourced model of education provision.

A PGA spokesperson said prison bosses had “limited influence” over third-party contracts, making it “difficult to address performance issues quickly”.

Providers also “struggle to attract and retain” skilled and motivated staff, who have to work with “disengaged and resistant” children who have sometimes been convicted of violent or disruptive offences.

Mark Fairhurst, POA national chairman, said the education data was “no surprise” since staff were “battling gang violence, threats and assaults”.

He added: “If we want a prison education system that delivers, the government must commit to building smaller self-contained units for young offenders and abandon the failed privatised education model by bringing education provision back in-house.

“Expecting teachers to educate young criminals whilst they continually try to kill each other explains why education provision is so erratic and unpredictable.”

Your thoughts