Jill Westerman had a very tough year in 2006 — the kind of year that might have persuaded others to consider their futures.

But instead, Westerman drew inspiration from the difficulties to step up and become principal of her beloved Northern College in September the following year.

“My youngest daughter Tanith was seriously ill with kidney failure,” she says.

“We took her to the doctor thinking she had a virus and within 24 hours she was in the children’s renal unit in Nottingham.”

The emotional turmoil of seeing 14-year-old Tanith suffering clearly still has an impact on Westerman, who struggles to tell me about it when we meet at the British Library in London, a regular haunt of Westerman’s.

was awarded a CB

“She had three bouts of peritonitis with emergency hospital admissions following the diagnosis of kidney failure and for some months we had to drive her three days a-

week to Nottingham for haemodialysis,”says Westerman.

“She never once complained, she was so ill and she never once said ‘why me?’ — she just got on with it.”

In the same year, Westerman’s father, Albert, who had struggled with dementia and had lost his sight, died at the age of 82.

In the middle of all of this, Ofsted arrived at Northern College, where Westerman was programme co-ordinator at the time, and as nominee, she was on the front line dealing with inspectors.

The college sailed through the inspection, scoring outstanding across the board — a standard it has maintained to this day.

“I’d never really thought of myself as a principal before,” says 58-year-old Westerman.

“But I just thought, if I can manage this, I can manage anything.”

She was she says, also inspired by Tanith herself.

“After two years, she was lucky enough to have a transplant, this was in her GCSE year, but she went on to get the best grades in the school.”

Tanith is now her third year studying medicine at Leeds University.

Westerman was also prompted to move into leadership by taking part in a senior leadership development course.

“It just really inspired me, both in terms of reading about the theory of leadership and being able to think about my own practice,” she said.

“That was almost ten years ago but many of us who were on the course, like Dawn Ward [now principal of Burton and South Derbyshire College] and Paul Wakeling [now principal of Havering Sixth Form College] still meet up.”

Westerman also spent time as a council member of the Learning and Skills Improvement Service (LSIS), which was closed and replaced with the Education and Training Foundation in August last year.

“It was a loss to the sector but we are where we are,” she says, adding that she is looking to the future.

Westerman is now chair of the Further Education Trust for Leadership (FETL), set up with £5.5m left over from LSIS and overseen by former LSIS chair Dame Ruth Silver.

“I think it’s really important to have that space to think, both for the individual principal and for leadership within the sector — and that space and time is something that’s difficult to find,” says Westerman.

“There’s a lot of research about leadership in schools, there’s a lot about universities but much less thinking has been done about the FE sector.

“We need to be thinking about leadership for the future, rather than focussing solely on present issues.”

I realised for the first time how much having an education means having power

and control over your own life

Westerman’s passion for education, she says, began with her mother, Sheila.

“She was very bright, very able, but she left school at 14 during the Second World War and I think she was frustrated that she’d never been able to go any further,” she says.

“So both she and my father drummed into my brother Roger and I how important education is and it is something for which I am eternally grateful.”

Roger, now retired, also went into education, becoming an education psychologist.

Under her mother’s encouragement, Wakefield-born Westerman passed her 11-plus and made it into the local grammar school.

However, at 18, the idea of going straight to university didn’t appeal.

“Nowadays it’s quite common to take a gap year – nearly everyone does it,” she says.

“But back then it was quite unusual.”

She initially took a job as a clerk at West Yorkshire District Council but within a few months decided it wasn’t for her.

Instead, she found herself teaching adults at the West Midlands Travellers School, and the experience of working with Irish travellers, she says, was a “real eye opener”.

“I realised for the first time how much having an education means having power and control over your own life — and how much these people who were already excluded from society were even more disadvantaged by not having education, not being able to read,” says Westerman.

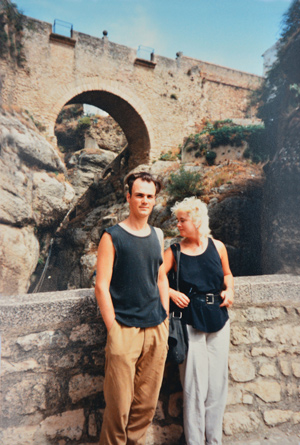

The impression was confirmed a few years later when, after studying English at the University of Durham and a brief stint teaching English as a foreign language in Spain, Westerman got herself a job as a community support worker on an East London estate.

“I’d been hired by the residents themselves,” she says.

“Because they were bright people and very clued up — they know all the facts and all the issues, but they felt that, because they didn’t have an education, they couldn’t hold their own talking to developers and the council and utility companies and so on.”

In 1985 she enrolled on a certificate of education course at Garnett College, where she met future husband Martin, also training as a teacher.

After the birth of the couple’s daughters, Aisling, now 24, and Tanith, and with the price of housing in London beginning to rise, they decided to move North.

And it was in May 1993 that Westerman first walked into Northern College for Residential and Community Adult Education, in Barnsley, as a part time lecturer and, she says, it was love at first sight.

“It’s in such a beautiful setting in a big old stately home and the ethos there was, and is, so committed to helping people change their lives,” she says.

“Everyone, from the leadership and management, to the receptionists, really care about our students.

“We’ve had people arrived at the door, take a look around at the surroundings and decide ‘this isn’t for me’ and I’ve seen the receptionists run after them, bring them back and take the time to talk them round and encourage them to come in.”

The college offers short, intensive residential courses, as well as year-long access to higher education courses, giving students time to focus on their studies, away from what can be quite chaotic lives.

“When you think about it, we’re actually very used to the idea of residential adult education — that’s what universities and a lot of management training are,” says Westerman.

“And I really don’t see why access to that sort of experience should be limited by class or level of education.”

After that turbulent inspection of 2006, the college has been re-inspected this year and maintained it’s perfect grade one scoresheet.

And as a keen promoter of the importance of leadership, how much credit does Westerman take for her college’s success?”

Well I could jokingly to go ahead and say ‘all of it’,” she says.”But actually part of you wants to say ‘it’s all down to my team, my staff and the wonderful work they’re doing, it’s nothing to do with me’.

“Of course, I think the answer is that it’s probably a little bit of both.”

What is your favourite book, and why?

This is a difficult question as I have so many favourite books. The Female Eunuch by Germaine Greer is not necessarily a favourite, but I read it when it was first published and I was 14. It fundamentally changed the way I viewed the world, made me a feminist and has influenced my life ever since

What is your pet hate?

Small anti-social acts, like able bodied people parking in disabled bays

What do you do to switch off after work?

Physical activity as a contrast to work. I do jive and ballroom dancing classes and like walking and cycling at weekends. I’ve run a couple of half marathons for charity. I’m also in a book group and a member of the Women’s Institute. I do my fair share of slumping watching DVD box sets, too

If you could invite anyone, living or dead, to a dinner party who would it be?

Mo Mowlam, who worked at Northern College but left before I arrived, Nelson Mandela — my ideal leader, President Jed Bartlet from the West Wing (I do know he’s not real, but it would be a privilege to hear him discuss leadership with Mo Mowlam and Nelson Mandela), Bruce Springsteen, and George Eliot [Victorian era writer], for her wisdom, compassion and understanding

What did you want to be when you were growing up?

I wanted to be either a famous author, because I liked reading, or an English teacher, because it was my favourite subject. I achieved my ambition as I did become an English teacher

Your thoughts