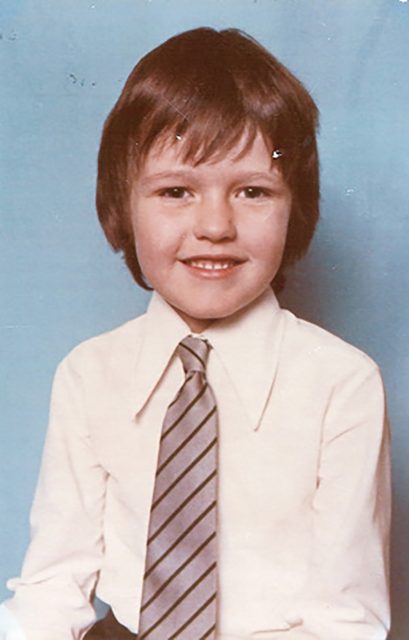

The new head of the Skills Network reveals the family and personal influences behind his career to JL Dutaut

Mark Dawe is a hard man to pin down. Just 18 months ago, the then boss of the Association of Employment and Learning Providers (AELP) was opening the FE Week apprenticeships conference with critical comments about subcontracting. “Its use as an income source for the lead provider with little benefit to the employer or learner certainly shouldn’t be accepted,” he then said.

Since this August though, Dawe finds himself at the head a large and well-established subcontractor. The Skills Network works, he tells me, with over 300 colleges, some 40 of them on subcontracting terms. The rest are buying in blended learning solutions, among other services.

But there is no dissonance in that for Dawe. He still holds his long-standing policy positions, advocating for a national cap of 20 per cent on management fees and clear sector guidelines. “I’m a great believer that if what’s expected is clearly defined – the quality mechanisms that should be in place, the monitoring, as much for the prime [the college] as the subcontractor – you can get really, really good delivery for those learners.”

But Dawe stops short of calling for regulation beyond the management fee cap. “When we’ve had issues like Brooklands College, that absolutely shouldn’t have happened, but under any rules, it should never have got to that place.”

If there was a more flexible approach to the funding, you wouldn’t need subcontracting

Brooklands was placed in “supervised college status” by the ESFA and underwent an FE commissioner review a year ago after it was revealed by FE Week that it had handed over £20 million to shadowy subcontractors who had failed to deliver the goods. For Dawe though, it seems, supply and demand should bring about the improvements needed to prevent another Brooklands-type scandal.

“I worked with The Skills Network when I was at AELP, helping put together what good practice looks like in subcontracting.” He goes on to list a number of ways the organisation holds itself accountable to the colleges it works with. It’s clear from his answer that he feels that if more subcontractors held themselves to higher standards, an element of self-regulation would make providers such as SCL Security Ltd, the company that received the £20 million from Brooklands, unmarketable to colleges.

But that’s the system as it is, and Dawe is more inclined to push for a substantial rethink of that system – one that sees colleges hold the purse strings and relies on their procurement acuity to deliver for students. Picking up on Boris Johnson’s announcement last month of a lifetime skills guarantee, extending to all adults the free first level three qualification that was previously restricted to under-23s, Dawe says: “If there was a more flexible approach to the funding, you wouldn’t need subcontracting. Something like 80 to 90 per cent of the national AEB [adult education budget] is grant-funded. Boris’s announcement is the beginning of skills accounts, as far as I can see. That puts the purchasing power in the individual’s hands, and then lets them choose which provider gives them what’s best.”

Two months into his new role, Dawe is already looking past the status quo – not just to a realignment of its priorities but of the sector as a whole. No doubt, his far-sightedness about the sector’s direction of travel was an attractive proposition for The Skills Network. So must his track record have been. Yet his appointment surely involved a calculated risk too; the very traits that make him a leader with vision also make him something of a non-conformist.

Doing these VAT returns. That was the moment I thought ‘This is it. This is me.’

Raised in Bromley in Kent and educated at the private Trinity School in Croydon, Dawe had a privileged upbringing. From Trinity, he hopped to Cambridge for a degree in economics and then to KPMG. Already, the choice of degree and profession was something of an act of rebellion. Dawe’s grandfather was a headteacher. His father was a senior civil servant with the DfE and Harold Wilson’s private secretary at Number 10. His uncle was a lecturer in FE. And if education hadn’t percolated, his mother was a nurse who today still volunteers in hospices. The family was ostensibly well embedded in the public sector, an ethos that can’t have failed to permeate the home environment.

But another influence came to bear on Dawe’s teenage years. Washing cars and gardening for pocket money, one day a neighbour and family friend invited him in to help him with his tax return instead. “And so I went indoors, was given a cup of tea and a Kit Kat, with Big Daddy wrestling on the telly, with a calculator doing these VAT returns for him. That was the moment I thought ‘This is it. This is me’.”

Warmth, tea and a pay rise helped, but Dawe still says he was “destined to be an accountant”. He remembers with evident excitement when his new employer got one of the first spreadsheet programmes to run on a personal computer – SuperCalc. “I learned how to use it and taught him, but then I used to do all his projections for all his clients when I was aged 14 and even then earning £5 an hour!”

But the family influence ran deeper than perhaps the rebellious young Dawe had realised, and it wasn’t long after joining KPMG that he changed tack. “I had a look up above me and it was ten years of tedious work to become a partner and I thought ‘Time to get out’.” It was 1993. Colleges were being incorporated and looking for accountants. Dawe made the jump. “I cut my teeth down at Canterbury College for seven years working for Sue Pember. We did all sorts of exciting stuff: building new colleges and prison education and a whole range of things like that.” Ironically, it wasn’t until he received a funding letter for Canterbury with his dad’s signature at the bottom that he realised the import of the work he did. “I genuinely had no idea. That was the first time I realised the connection between the job I just got and what my dad was doing.”

When I joined, AELP was known but not listened to as much as it should be

From Canterbury, Dawe moved on to his first dalliance with e-learning as group education director for eGS, a company founded by Labour MP Liam Byrne. Three years later, he found himself working with Pember again, this time at the DfES on the adult basic skills and further education strategies. Another three years later, he turned his back on national strategy to get stuck into local implementation as the principal and chief executive of Oaklands College in Hertfordshire.

“To be fair to the governors, they took a risk with me,” he says. “I think I was against four other existing principals.” That risk paid off. Within five years, Oaklands had gone from ‘unsatisfactory’ to “solid ‘good'”. That mission accomplished, Dawe sat down with the governors to talk about his vision for the next phase. “I wanted to bring Hertfordshire together as one college. We had very open discussions, but they weren’t really up for it.”

A pattern emerges, and Dawe is frank about his “five-year cycle”. He joins with a vision, delivers the goods, stays long enough to be held accountable and then: “I have a view on how I could stay on in a role,” he says, “and if not, I agree to move on.”

Five years at Oaklands were followed by five years as chief executive of OCR at the time Ofqual was being created and “sharpening its teeth and claws”. Of the current exam travails, he says: “You can never do an excellent job in the exam board, because everyone just expects you to perform well. But anything that goes wrong is a massive negative because it affects people’s lives.”

After OCR, a short stint working with the FE commissioner’s office under Sir David Collins led him to the AELP job. “When I joined, membership was down about 500. AELP was known but not listened to as much as it should be. It was just a year before the levy was being introduced and the board was very keen to have someone to drive the AELP agenda.” He describes a period when “the employer was king and the provider was pushed to one side” and “public battles because we weren’t getting anywhere in private conversations”.

I had people calling me who had refused to take my calls for the previous four years

In August, he left an organisation with a renewed membership and a reinvigorated voice in the sector. But for all the battles over that period, the real breakthrough, he says, came with Covid. “It was like a 180-degree shift almost overnight. I had people calling me who had refused to take my calls for the previous four years.”

The calls came because AELP had grown into its position and was ready to receive them, testament to another transformative half-decade.

It’s a truism to say that nobody knows what the sector will look like post-Covid and post-Brexit. And it’s probably not even all that true. Taking Dawe’s far-sightedness and his move to The Skills Network into account, it’s clear that blended learning and independent provision are likely to be key battlegrounds.

And Dawe is ready for those fights. You won’t pin him to a clear career trajectory, but you can certainly pin him to that.

Your thoughts