As a teenager, Lord Willis of Knaresborough, a former head teacher, ex-Liberal Democrat MP and outgoing chair for the Association of College’s charitable trust, dreamed of a career in football.

But although Burnley-born-and-bred Willis (known, less formally, as Phil) played for Burnley FC junior team, he wasn’t good enough to make the cut for the senior team.

Having left school to unsuccessfully pursue his dream, he found himself faced with going to one of Burnley’s 200 cotton mills to find work, until his postman father, George, intervened.

“My father frogmarched me back to school and said: ‘You’re not going to be a postman’,” says Willis.

George’s insistence on education stemmed from his own experience — he had passed his 11-plus but been unable to go to grammar school because his parents couldn’t afford the uniform.

“He resented that until the day he died,” said Willis, aged 73.

“And the fact that my brother then failed his 11-plus was horrendous, and then that I had passed it but wanted to give up grammar school, he couldn’t cope with that at all — so he was determined, he took me back and pleaded with the head to have me back in the sixth form.

“And it was the best thing he ever did.”

Willis’s childhood, he says, was “a very happy childhood, but a very unhappy one”.

George had been a prisoner of war for four years in the Second World War and returned “a wrecked man”.

“He could never really engage with humanity after he came back,” says Willis.

Willis’s mother, Nora, was a nurse from Donegal, and it was she who instilled an understanding of the importance of qualifications in him from an early age.

“What my mum wanted to be most of all was a district nurse on a bicycle, and she had to be a registered nurse rather than a state-enrolled nurse to do that,” he explains.

“And I can remember literally being in her bed in the morning when the postman came with a letter saying she had passed and become a registered nurse.

“And I couldn’t understand why she was crying — it seems very strange to me, because I read the letter to her, and it clearly said that she had passed, and yet she was in bits. I think I recognised, even at that early stage, how important education was.”

Nora died when Willis was 13, leaving George “just utterly and totally broken” and “drinking heavily” as a result.

“School was the only thing that kept me sane, and school was just fabulous,” says Willis.

“I had wonderful teachers who picked me up, disciplined me, made sure my nose was kept to the grindstone, and without them I would have definitely gone off the rails — because I was a very troublesome kid.

“It is meeting inspirational people who you aspire to be like that actually keeps you motivated to move forward.”

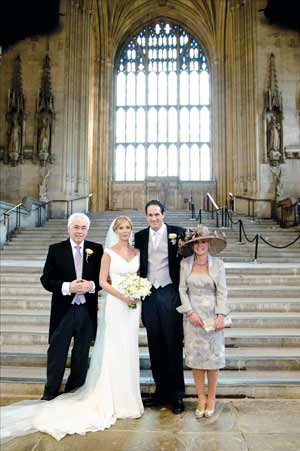

Despite his early experience of tragedy, Willis, a dad-of-two, comes across as gruffly optimistic. “Looking back, there wasn’t a lot wrong,” he says.

“I can remember listening to kids as a head, and when I was teaching, bemoaning what they haven’t got, and I used to get really irritated — you know, you’re fit and healthy and you’re reasonably intelligent, you know, you can do whatever you like.”

Once back at school, Willis developed a new ambition — teaching.

“I think it was because I had so many inspirational models as teachers when I was at school,” he says.

“Not only were they good teachers, but they just loved imparting knowledge.”

The idea of inspiration, for Willis, seems to have been central to his work as a teacher and an MP, and later with the Association of Colleges.

“I think inspiration and aspiration go together,” he says.

“You cannot aspire to something unless you have somebody or something which you regard as inspirational — it’s a mistake to just say you should aspire to go to university.

“Why would anybody aspire to go to university, unless they knew people who were inspirational, who were at university and the same goes for technical skills. That’s the bit that we’ve got to connect with.”

Thirst for equality for people, whether they are adults or children, who are genuinely in need of support in order to be able to access a level playing field, it’s become a life mission

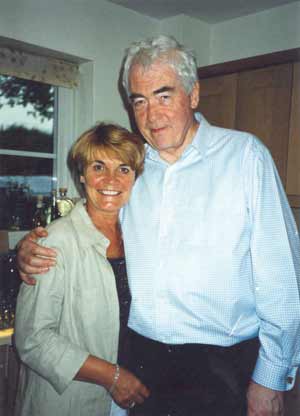

After completing teacher training at City of Leeds and Carnegie College (now part of Leeds Metropolitan University), he moved through various teaching roles in and around Leeds, including senior master at Primrose Hill High School, where he met wife Heather, then a PE teacher.

In 1979 he became head of Ormesby School in Cleveland, which was pioneering the integration of severely disabled youngsters into mainstream education.

“I just loved that school,” he says. “We integrated every child with severe physical disability south of the River Tees into a school over a period of about four years — and it was an inspirational journey.”

Willis may have loved the school, but he hated being a head.

“I became a head in 1978, the year before Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister,” she said.

“So virtually all my headships from ’79, right through to ’97, were really under a regime which changed the face of education.

“And I just felt as a head that what I was doing was balancing books. I was a bureaucrat — and I wasn’t good at it… being in a classroom was so much more exciting than that.”

He was headhunted to run John Smeaton Community School, where he set out to introduce the same principles of integration.

“Being able to say no child should be left behind because of their disability — that really has stayed with me in my political life,” he says.

“That thirst for equality for people, whether they are adults or children, who are genuinely in need of support in order to be able to access a level playing field, it’s become a life mission.”

For the first time, Willis found himself living outside of his school’s catchment area in a small village and became embroiled in a local environmental campaign against a landfill site slated to be built on the outskirts of the village.

“And I realised that unless you are on the inside when decisions are made, you can forget about affecting change,” he says.

“And so I said, ‘Right, I’m going to start’.”

In 1985, and at the age of 44, Willis joined the Liberal Party, which would later merge with the Social Democrats to form the Liberal Democrats, and in 1988 won a seat on Harrogate Borough Council, becoming council leader two years later.

His arrival in Parliament was a surprise — he ran against Norman Lamont in what had been considered a safe Tory seat, Harrogate and Knaresborough, and took it from him in 1997.

But a seat in Parliament wasn’t all he had hoped it would be, thanks to Labour’s huge majority.

“When I was leader of Harrogate Borough Council, I genuinely felt I could make a real difference,” he says.

“You could literally make decisions and officers would carry them out.

“And coming into Parliament was a huge disappointment because suddenly you find you are in a minority party on the periphery of things.

“So you found other ways to work, really. I spend a huge amount of time in my constituency.”

In 2010, Willis lost his seat in the Commons, but gained one in the Lords.

“I didn’t like it when I first came,” he says.

“It was just too polite, too genteel, everybody was so nice — I am suspicious, you know?”

And it was in the Lords, unimpressed by free schools that he moved away from school policy and developed an interest in science policy, and FE.

“I felt the FE agenda was totally and utterly ignored over the last five years,” he says.

“I cannot remember a single serious debate on FE in the House of Lords. It was merely a pawn of the Department.”

But, he says: “It’s its own worst enemy —the FE sector constantly says, ‘We’ll make it work. No matter what’s thrown at us, we’ll make it work’.”

And, although he’s not sure he’d go back into politics now — “Politicians are regarded with such contempt, I just don’t think it’s worth the sacrifice, to be honest,” he says — he’s got no regrets about making the leap.

“It’s been this wonderful opportunity,” he says.

“Doors open, and you either go through the door, or you don’t, but don’t moan about it if you didn’t.”

————————————————————————————————————————————–

It’s a personal thing

What’s your favourite book?

I don’t read fiction, but two years ago I came across Stieg Larsson and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, and I read the whole trilogy right through to The Girl Who Kicked the Hornets’ Nest and I just loved that genre. So I’m addicted to Swedish crime/thriller fiction. I just found it really quite exciting.

What do you do to switch off from work?

Sport. I follow Leeds United and I’m addicted to sport. When I was a youngster football and athletics were my great passions. Now, my wife and I regularly go to Leeds United games. We follow cricket, and we go to different places in the world to watch Formula One.

What’s your pet hate?

You’ll find this very petty, but I hate people who are fit and active parking in disabled and parent-only bays in supermarkets. My wife pulls me away and says: “Don’t say anything” — but it really annoys me. It’s petty, but it’s true.

If you could invite anyone, living or dead, to a dinner party, who would it be?

Former Lib Dem leader Charles Kennedy. He was a great friend of mine and we were incredibly close for a number of years, and I used to spend, when I first came into parliament, far more nights than I should have done in his flat in Victoria where we used to have an eclectic group of people who would come and just simply chat and tell stories and raconteur, right through until the early hours.

Since I left the House of Commons, I lost touch with Charles, so his death came as a huge shock, and I would dearly love to have him back at a dinner party and to be able to rekindle some of those wonderful experiences. He was quite a remarkable human being.

What did you want to be when you were growing up?

I wanted to be a footballer — that was my great desire.

Your thoughts