Last week, ex-NCG (Newcastle College Group) chief executive Jackie Fisher spoke exclusively to FE Week about her notorious 2012 Ofsted inspection.

She explained why she booted the education watchdog out of the college mid-inspection before calling for the Ofsted complaints-handling procedure to become more transparent.

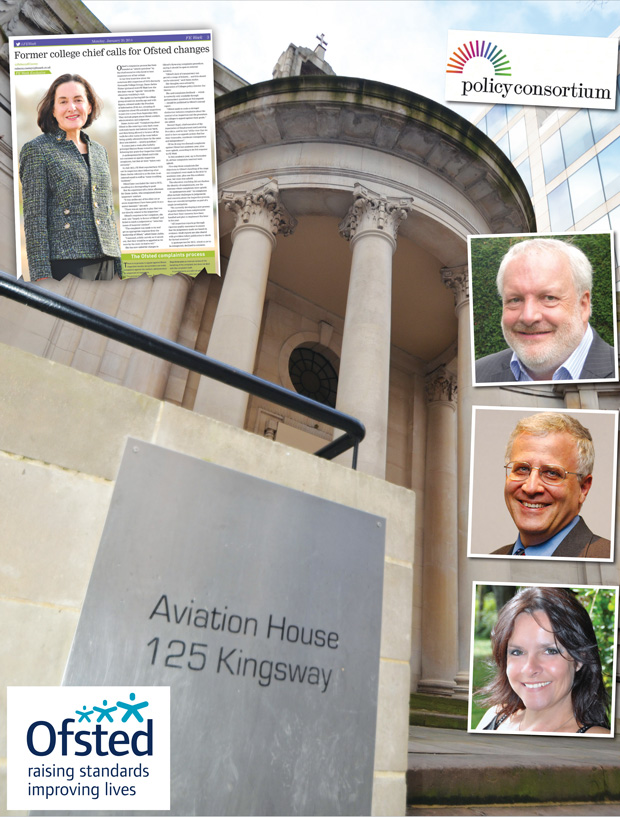

Here, Policy Consortium trio Colin Forrest, Mike Cooper and Carolyn Medlin look deeper into the Ofsted complaints issue.

Over the past six months, we’ve written about how well or otherwise Ofsted supports improvement in the FE sector, as it claims — and how it might improve its own approaches.

And last week’s FE Week article, although centred on NCG and its former chief, was underpinned by revealing insights into Ofsted’s published inspection complaints system.

In short, there were 35 formal (‘Steps 2 and 3’) complaints from September 2012 to mid-November 2013 — 29 ‘Step 2’ complaints. That’s around 12 per cent of approximately 250 inspections undertaken over that time — 13 of those (around 5 per cent) were upheld. At least one produced a significant uplift of grades from ‘requires improvement’.

It’s not clear what the full spectrum of ‘successful outcomes’ to complaints has been, but that may include other grade changes, or significant changes to report narratives (without change to grades or judgements).

There is no indication of the scale of informal ‘Step 1’ concerns about processes. This proportion of complaints upheld might be seen as relatively minor, and thus acceptable.

Nevertheless, the context of an inspectorate making more and more stringent demands on providers suggests improvement is required here from Ofsted. And it’s so important to get this right.

Apart from damage to reputations, funding may be at stake, since grade three and four providers may be excluded from some provision and growth.

Inspections, of course, can cover only part of a provider’s activity — but findings can be seen as applying across the organisation.

It was good to read that Ofsted has reviewed its complaints process

One particularly contentious aspect is that reports are published to fixed timescales, even if the process is subject to an appeal or complaint.

The stated procedure suggests this is non-negotiable, apart from in (unspecified) ‘exceptional circumstances’. Anecdotally, this is characterised as “Learners and employers have a right to know the truth!”

Ofsted does allow up to 48 hours for an accuracy check, but that is not a test of the findings’ validity. It allows no debate on judgements or grades, since it focuses on spellings, learner numbers, and so on. There may also be other factors, including the implications of short-notice inspections.

The compressed window for dialogue between lead inspector and provider limits potential for sharing information and adjustments to the expertise available within the inspection team. It also compromises opportunities for the provider’s input into the pre-inspection briefing. This may increase the potential for more complaints.

It was good to read that Ofsted has reviewed its complaints process. However, the role of providers (and other ‘consumers’ of inspectorate outputs) isn’t clear in that review. That is crucial, to reduce dissonance between improvement approaches which the inspectorate looks for in providers and their treatment of complaints.

Consultancy for Free was the title of an excellent short publication setting out simply and clearly the case for FE providers to make serious, thoughtful use of open, well-constructed, responsive complaints systems — and to generate real improvement from that.

Perhaps Ofsted ought to take those strategic messages about transparency and accountability very seriously in implementing its review?

Your thoughts