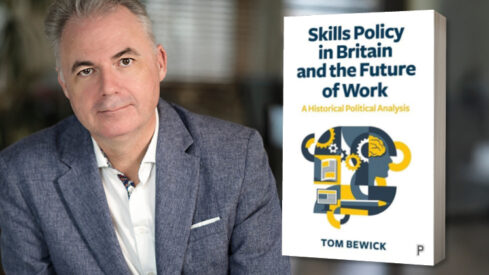

If history often rhymes, as Mark Twain once said, then Tom Bewick’s book, Skills Policy in England and the Future of Work, is a poignant poem of political déjà vu that should be required reading for our skills policymakers and shapers.

As “a product of FE” who went on to help shape the skills system at its highest levels, Bewick has spent the last three years poring over 4,000 artifacts in the National Archives, some only recently declassified, to document not just the history of our skills policies but the real motivations of the politicians and civil servants behind them.

Its 290-pages depict a mournful tale of oft-repeated warnings about the urgent need to prioritise technical skills training. Noble attempts at reform are all too often stifled by the overriding counterforces of civil service resistance, red tape, funding constraints and a snobbery against FE.

In one eye-popping revelation, civil servants in 2010 recommended to business secretary Vince Cable the closure of every FE college, with one official remarking “nobody will really notice”. “That belies a certain attitude that exists within Whitehall,” says Bewick.

He hopes his book, out next month, becomes an essential text for aspiring, as well as current, policy officials. You may need to be an economist to advise the Treasury, or a qualified planner to advise on the environment, but he finds it “extraordinary” that “virtually anyone can become a skills policy adviser”.

Almost every former minister and senior civil servant interviewed for the book “indicated that they’d fallen into it by accident”. This is partly because skills policy is “relatively new” – university departments do not teach graduate programmes in skills policy. So officials tend not to be “specialists”.

Bewick’s aspiration is that his book will, “in a small way, contribute to the idea that skills policy does have an intellectual hinterland, you can’t just come in as a gifted amateur and think you can solve the skills crisis. I hope it helps shift the dial on those amateurish attitudes”.

FE lifeline

His passion for FE evolved from the fact the sector gave him a second chance.

Bewick’s mum died young, his dad was a gambling addict and he was placed into care aged five. He left school with no qualifications. Opportunities “opened up” to him after he attended evening classes at his local FE college, North Warwickshire College of Technology and Art (now North Warwickshire and South Leicestershire College), while working at a supermarket.

At that time in the 1980s, he was one of over a million adults in ‘night schools’ at over 500 colleges. In contrast, Bewick describes colleges now as “on the whole 16-to-19 exam factories”.

In his book he charts how, going as far back as the mechanics institutes of the 1880s, technical colleges were “bottom-up working-class self-improvement vehicles”. Now they are “just delivery arms of the state”.

Looking through “that long lens of history”, Bewick feels fortunate to have accessed an FE college that was able to “mould its offer” around him. He is pessimistic he could access similar opportunities today.

Dream come true

Bewick pursued a career crafting skills policies in government, then influenced skills policy at various think tanks, quangos and skills associations, including the Federation of Awarding Bodies.

As an active member in the Labour Party from 1990, he was “very much part of the internal party discussions about what should be in the 1997 manifesto, albeit more as an observer”.

Becoming the party’s post-16 education and employment policy officer when Labour came to power was “a dream come true” as Bewick felt Labour was “building a new Britain where social class would no longer be a barrier to opportunity”.

He wishes a book like his was available to him then.

Bureaucratic market centralisation

Bewick’s book claims the real reason for policy churn and rise and fall of so many skills-related institutions over the decades is because Britain lacks a consensus about how to finance and organise post-compulsory education and training.

The country instead has a “national obsession” with structural reform, which he also pleads “guilty” of having himself when he was a ministerial adviser in the early 2000s.

To make sense of decades of stop-start reform, Bewick sets out four “training states” that define the post-war skills landscape. It begins with the interventionist state (1939-79), where government steered training directly, to the laissez-faire years of Thatcherism (1980-88), through the localism era (1989-2010) of Training and Enterprise Councils and regional experiments, and ends with today’s technocratic state (from 2010), ruled by quangos, metrics and ministerial pilots.

His central argument is “bureaucratic market centralisation” (top-down state intervention) has been the dominant policy paradigm since 1981.

In the 1990s, this morphed into what he terms “quasi-market centralisation” through its “managed provider market, funded and monitored via a battery of arms-length agencies and regulators,” and Whitehall becoming “more adept at shielding the central bureaucracy from criticism”.

Bewick points to three policies from that era – individual learning accounts, Train to Gain, and employer-owned sector skills councils – which he believes, had they been adequately supported by officials, would have successfully decentralised the skills system. As someone who wrote the proposal for sector skills councils, he is hardly impartial.

Official shot taken when Bewick joined the Labour Party HQ in London 1997 as its post 16 policy officer educaton and employment

Top secret

Bewick is a gifted writer when given free rein on a topic he loves, as anyone reading his opinion pieces will know. But as his book also forms the thesis of the PhD he is taking through the University of Staffordshire, it is by nature academic. Bewick the astute commentator is at times bogged down by his need to show academic rigour.

He nearly gave up writing it four times. “It was intellectually very challenging, more so than I expected,” he admits.

But Bewick’s meticulous research reveals fascinating contradictions between the private and publicly stated motivations underlying certain skills policies.

Thatcher’s Youth Training Scheme (YTS), which gave young people compulsory (but poor quality) training in return for allowances as an alternative to putting them on the dole, was, Bewick states, used to “manipulate the official unemployment count”.

His evidence lies in a memo marked ‘secret’ from Thatcher’s adviser Oliver Letwin, recommending it was better to subsidise low pay through in-work benefits for the unemployed than to engage in the more ‘expensive option’ oftrying to reskill those on benefits.

He is also scathing about the “murky” process the Thatcher government used to abolish the industrial training boards which had been established in 1964 to get employers to pay for training for employees through a levy system.

He cites this, and the expansion of tertiary education since the 1990s, as examples of the “massive transfer of responsibility for skills acquisitions from employers onto the financial shoulders of the state and individuals” that has happened since 1981.

Cathartic writing

Bewick has an unavoidably biased view of the skills policies that he helped to shape, and admits to sometimes writing as “Tom the polemicist, not Tom the scholar”.

But the book’s most fascinating elements are when he channels frustrations he must have felt as a government adviser at seeing civil service officials sabotage policies that he championed. Writing it was, he admits, “cathartic”.

For example, he describes how a policy he strongly endorses, the Individual Learning Account (designed to give money to individuals to train, with added contributions from employers and the learners themselves), “went through the departmental mincing machine” before emerging in a diluted state.

Bewick’s old boss, former education and employment secretary David Blunkett, blamed the Treasury for not wanting to work with banks to open accounts. “They wanted and got a cock-eyed voucher system, which was then open to abuse,” he tells Bewick.

Civil servants chose Capita, an outsourcing firm with no experience in devising financial payment systems, to implement the scheme. It was 40 per cent over budget even before accusations of significant fraud emerged.

There are lessons to learn here for those now working on the rollout next year of a policy with similar objectives, the lifelong learning entitlement, intended to enable learners to access loans for some courses at level 4 upwards.

The late Lord Tom Sawyer who was general secretary of the Labour Party with Bewick

Civil service accountability

The permanent secretary of the Department for Education and Skills (DfES) at the time, David Normington, “absolved” himself when hauled before the public accounts committee, saying it was “inexplicable” what his colleagues had done. He was later awarded a knighthood.

Bewick quotes an unnamed former DfES minister as saying the saga “raises legitimate concerns about how far career civil servants, particularly those who assume leadership positions, are themselves held to account for the decisions of the people they are said to be accountable for”.

The problem of civil service culpability still looms large today for Bewick.

Skills minister Jacqui Smith last year declared that “the skills system is failing individuals and our country”, as her government embarked on yet more significant structural reforms. But to blame the Tories for the ‘failing’ system is an “incongruence”, says Bewick. Her predecessor, Robert Halfon, was “one of the more effective skills ministers”.

“To come to office and say, ‘it’s all the fault of the Tories, but then just to carry on working at the highest level with the very same people who advised those former ministers… because, when you look at the policy decisions made since those ‘nasty Tories’ went away, we’ve seen a continuation of that departmental philosophy, for example with the cut in adult education.

“I don’t believe for a minute Labour ministers really want to make those cuts, but they’re put forward to them by senior officials who don’t value adult education.”

Cinderella’s origin story

Bewick wants to end the binary divide between FE and HE by creating a single tertiary education sector, potentially ending the entrenched perception of FE as the ‘Cinderella’ of the education system.

Readers will be familiar with this often repeated analogy (most recently used this week by education committee chair Helen Hayes).

Bewick unearthed what he believes was the first time it was used in reference to FE, in a 1982 confidential memo from Treasury minister John Wakeham copied to then-chancellor Geoffrey Howe.

Calling for a ‘coherent strategy’ for FE to be directed not by the Department for Education and Science but the Department of Industry, Wakeham attacked the “largely anti-industrial, anti-commercial and anti-entrepreneurial” education culture and described FE as “a Cinderella of the education service”.

This tussle over skills between departments reflects how skills policy has long been “the orphan of Whitehall”, being passed from one department to another. There have been six iterations of skills in various departments since the year 2000.

Since the 1990s, employer investment in training has slumped. The UK investment per employee is around half the EU average, with a knock-on-effect on productivity and the take-home pay of workers. The stakes could not be higher for current skills policymakers to get things right.

This book serves as a crucial lesson in what not to do when drawing up skills policies.

Bewick and I have been sitting in a restaurant high up in London’s Shard building, enjoying sweeping views over the financial heart of London. Bewick-the-education-consultant has another meeting now on a different floor with a Saudi delegation.

The setting is a far cry from where he grew up in Nuneaton, a place he now sees as a “metaphor for what’s gone wrong outside of London and the South East” with its “boarded up shops, charity and gambling shops everywhere”.

“You see how the Palace of Westminster really dominates the landscape,” he says gesturing out the window as he bids me goodbye. That much never changes.

Skills Policy in Britain and the Future of Work: A Historical-Political Analysis is published on October 29.

Your thoughts