Isle of Wight College principal Ros Parker tells how her passion for adult education was sparked by village hall sessions that led her, and her young daughters, out of poverty

Parker’s incredible story captures the life-changing power of adult education far better than numbers and data ever could.

As a hard-up single mum aged 25 struggling with mental health problems and with no job or qualifications to her name, an evening creative writing course in a village hall changed her life forever. She went on to teach, then rose through the ranks of councils and colleges to lead FE provision on England’s sunniest shores.

A particularly harrowing memory sticks in her mind of her two daughters, Emily and Boo, sat at the kitchen table of their rented home in Essex waiting for their dinner. She could not bear to tell them that she had nothing to give them.

She had already gone without dinners herself many times before that – and she weighed just six and a half stone. “All I was doing was surviving for my two little girls,” Parker says.

She “couldn’t look” at Emily and Boo and instead looked out the window – where she spotted her neighbour approaching to offer a bundle of fish he had just caught.

“I knew from that day onwards that I had to change my stars.”

Growing adult education

Parker’s story of how joining an adult education course “saved my life” is particularly poignant given providers are bracing for yet more funding cuts.

But on her island, Parker is committed to investing in adult education opportunities amid soaring demand.

When her college advertised a course in carpentry and welding last year, it had to close early after receiving 500 applications overnight. Parker plans to open more evening courses next year because “we need more people in construction”.

“We’re missing so much just thinking about 16 to 18 when we have these massive skills gaps to fill,” she says. “And it’s important people feel they have a second chance in life.”

Survival skills

The years leading up to Parker’s own second chance were “really hard”, but gave her strong survival skills. After giving up an office job at an insurance company when she became a mum aged 18, Parker and her then husband spent two years living in a caravan before moving to a small farmhouse in Dengie marshes in Essex, two miles from the nearest neighbour. They drank water from a well and huddled in a room with a fire to keep warm.

Parker kept rescued chickens for eggs and learned from library books how to grow vegetables, spending her £4 weekly budget on potatoes and flour, with “all day Fridays spent baking”.

She was used to coping with “next to nothing”. But after being compelled to move out with her daughters (then four and seven) she “actually had nothing” – with no child support, chickens or vegetable patch to fall back on.

Parker felt “broken” and “not in the right mental health to cope with a job”.

Instead, she started making money by writing articles; a crafts magazine paid £10 for her idea for making a caged Easter bunny using tangerine bag netting and cotton wool buds.

Courage calls

She wanted to join a local creative writing class, but was so nervous at the prospect of returning to education that it made her physically sick the night before.

Parker had always hated school. She had spent a year out of primary school while living in different holiday parks after her mum split up from her father. After “always being at the bottom for everything,” she left school aged 15 with no qualifications.

“It took all my courage to go back into an education setting,” she says. “It was only the fact it was in a village hall that enabled me to go. If it hadn’t been for that class, I don’t know where I’d be now.”

When her creative writing teacher retired, she was encouraged to apply for his role. The adult community college’s principal saw something in Parker that “no one else had seen” and laid on a Saturday creche so she could do her teacher training, and English and maths qualifications. Within two years she was a team leader, teaching dance and drama to adults with learning difficulties.

She says: “I started caring so much about the difference education makes to people’s lives because it saved mine. I wanted to share my experience.”

At this point I am moved to tears – something that does not normally happen during interviews. Parker hands me some tissues before continuing. I am moved not just by Parker’s heartrending story in the light of adult education budget cuts, but how her experiences have clearly shaped her caring and inclusive approach to leadership.

As she walks around her college, she tenderly refers to the learners she greets as her “luvvies” and “gorgeous ones”; they call her “Ros”.

Courage calls

While teaching in Essex, Parker ran a family learning project at Bullwood Hall women’s prison in Hockley which gave her extra cash to take her daughters to the cinema for the first time, and led to a job teaching English there. As a child, Parker’s father had been a prison officer at HMP Hollesley Bay in Suffolk.

Parker helped her learners produce a book, ‘Inside Out’, about “their feelings inside prison and their hopes for the future”.

One particularly “troubled” inmate who was “very dependent on the services around her” was “very nervous” about being released, causing her one day to throw a chair across Parker’s classroom. Prison officers came “storming down the corridor to restrain her”. Before being escorted away, she turned to Parker and said “I just want to say thank you for turning my life around”.

Another girl, aged 17 when she was locked up, was “heartbroken” she could no longer care for her younger autistic and deaf twin brothers.

Parker helped her make an alphabet book for them, but on visiting day she was so scared they would not like it that she started shaking. When they entered, she “swept them up in her arms” and Parker looked on with pride as the girl read to them for the first time.

Refusing to cut

She moved on to West Sussex to lead the council’s adult learning service and later as it transferred to a new charitable company.

Although other areas were cutting their community learning provision, Parker went “against the curve” by refusing to do so, instead subsidising it through contributions from those who could afford to pay.

A report she compiled found the council’s “small investment” in adult education saved £250,000 a year on health, wellbeing and welfare savings. Parker smiles as she recalls how, when asked whether her yoga class kept her healthy, one elderly lady remarked: “My dear, the doctor doesn’t even know who I am.”

She would “batten down the hatches” on the weekends that her daughters were staying with their dad to study for her degree, and later a master’s in education and training. Studying “distracted” her from not having them around.

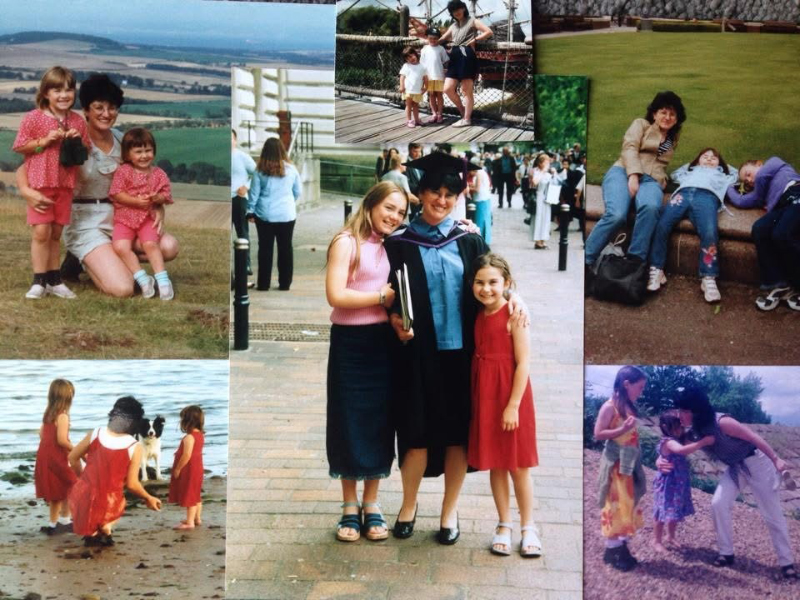

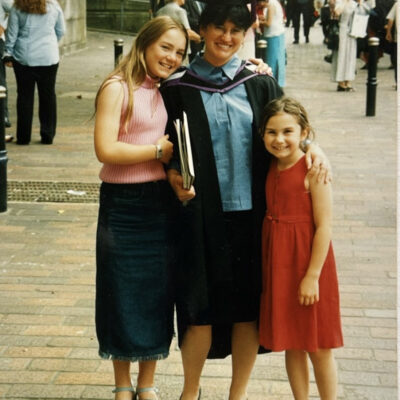

A photo of Parker’s graduation, her daughters at her side, is “very poignant” because they were “an inspiration” to her.

Back to Essex

Parker then returned to Essex to head up the council’s ‘delivery transition’, tasked with making council-run school crossing patrols, county parks, sports and leisure and adult education services “more viable”. It gave her the opportunity to turn what she had learned in her career so far, “sometimes in quite painful ways, into something positive”.

Parker next joined Prospects College of Advanced Technology in Basildon, a former independent training provider specialising in engineering and construction, before taking the helm at Southend Adult and Community College where her “biggest issues” were gangs who would “storm the building to sell drugs – they weren’t frightened of going into a class and actually picking kids out”.

During Covid, college rooms were emptied for the local authority to use as morgue space. Fortunately, they were never needed.

Parker and her colleagues also prepared and delivered 4,000 meals for the homeless staying in local hotels at that time, as “the council and charities couldn’t cope”.

In 2021 she was awarded an OBE in recognition of that work.

The following year she became Isle of Wight College principal, and when that community was hit by crisis 12 months later – serious flooding to over 300 homes – she opened the college’s doors for residents to shower, wash clothes and charge devices.

Island life

Moving to the Isle of Wight proved a “gentler way of life” than in Southend, but the island has its own challenges.

The seasonal highs and lows familiar to all college staff are particularly acute. With the holiday season now picking up, student attendance drops off as work opportunities take precedence for many learners.

The college engages in a “massive push on attendance” until the Isle of Wight festival in June to “front-load” learning and “get them through the qualifications as early as possible”. “Then if their attendance does start getting erratic, at least they’ve got their qualification in the bag”.

In many ways, Isle of Wight College has more in common with those on the Channel Islands and the Outer Hebrides than English colleges.

Parker recently visited the Hebrides, which share the Isle of Wight’s “stark” demographic challenges, to discuss “how they were managing to continue to be financially viable and innovative”.

The Isle of Wight’s birth rate has dropped by a third (the number of children entering school is forecast to fall from 1,404 in 2018 to 920 in 2027) while its elderly population continues to grow, resulting in skyrocketing demand for adult social care.

The top floor of the college’s pink block mimics two hospital wings and boasts an immersive room that releases hospital smells including “sick and poo” to “prepare” learners for the realities of caring roles.

Locked in

Being cut off from opportunities on mainland England can be a barrier for Parker’s learners. She introduces me to graphic design student Tim, who will commute by ferry from his island home when he starts at the University of Portsmouth in September, but knows “there will be times when I’ll miss lectures because I can’t get across that tiny little stretch of water”.

“The ferry is just not reliable and feels quite tethering, like we’re locked in by capitalism,” he tells me.

For many other learners, Parker says the costs of leaving the island prohibits them from aspiring to university. The college is a university centre, and Parker’s “big ambition” is to expand that provision so in the future “no one should have to leave the island for healthcare, education or employment”.

The college operates in every vocational area and Parker offsets the cost of smaller classes against larger-sized ones.

But her biggest passion is adult education.

From being potentially destined for a life on benefits, she is now “paying back thousands in tax and National Insurance and transforming the lives of others”.

Her message to the government now is a simple one. “Your small investment in adult education changes futures forever. Don’t write off adults. They’re the ones that can retrain and become your future leaders.”

Your thoughts