Liam Sloan greets me at the doors to Bolton College where he welcomes his students every morning. He has the warmth and immaculate tailoring of a man determined to make a good first impression and the firm handshake of one unafraid of high-pressure challenges.

After eight years spent running colleges in New Zealand and Australia, Sloan returned to our shores a year ago to take over Bolton College, which was reeling from a ‘requires improvement’ downgrade and financial turmoil.

Only weeks into the job, he found himself blindsided by the allegations of financial misconduct and racism engulfing its parent university.

But for now, as he ushers me inside to buy me a coffee, his focus is fixed on other matters; making Bolton “the jewel in the crown of the FE sector”.

A Māori welcome

Sloan’s welcoming gestures are not just because he is endowed with Scottish charm; they carry special meaning as his equivalent to a Pōwhiri,a traditional welcoming ceremony given by the Māori in New Zealand.

Upon moving there in 2016 and starting as executive director of learning, teaching and quality at Nelson Marlborough Institute of Technology (he became CEO a year later), he was not allowed to set foot on campus until he received the chant. He tells me he feels the hairs on his arms stand up as he recalls the Māori embracing him to “please come help us with the challenges we are facing in education”.

NMIT held an ethos of “what’s right for Māori is right for anyone, because they’re the most disadvantaged”.

Their “very inclusive” attitude changed how he “valued and embraced people”, reflected in how he talks about his learners now: “I try to pay as much attention to the T Level learner with a great GCSE profile as trying to retain someone on 40 per cent attendance,” he says.

Sloan found Australia’s treatment of its indigenous people “shocking” in comparison.

He is taking the Pōwhiri example of creating positive first impressions to overhaul his staff induction processes, which are currently a “weakness” of the college.

Mundane form-filling and health and safety checks are to be done online in advance, freeing up time on an employee’s first day for “meeting the leadership team” and being shown that “we’re grateful you chose us”.

Sloan’s dapper ensemble – a pocket square paired with a floral tie and grey waistcoat – is a nod to his past; he began his career in fashion retail. He joined C&A’s graduate management scheme after studying business and human resources at Huddersfield University.

After managing stores in Nottingham and Northampton, he returned to Huddersfield for teacher training, working evenings managing Barnsley College’s training restaurant before taking on his first full-time teaching role at Doncaster College.

His principal then was George Holmes, who subsequently became vice-chancellor of the University of Bolton (now Greater Manchester) and, 26 years later, was once again Sloan’s boss.

Holmes and investigations

On Sloan’s first day at Bolton last December, Holmes gathered his staff to introduce the new principal before declaring to much “cheering and clapping” that they had just received government approval to change their name to University of Greater Manchester.

This did not go down well with neighbouring universities; the University of Manchester described it as “very misleading and confusing”.

But Holmes was “one of the attractions of the job” for Sloan, who assumed the group’s unusual HE-FE structure meant he would have an “understanding of the importance of colleges” and would be “somebody that I can sound board off…because it’s a very lonely job otherwise”.

Holmes seemed to be at the top of his game. After 20 years in the role, the previous financial year the group’s remuneration committee had raised his pay package from £340,954 to £359,592 (despite the group making 82 staff cuts) on the grounds that “thanks to [his] leadership, his extraordinarily successful wilful institutional building and his financial foresight, the university is potentially well placed to weather the storm generated by many fierce headwinds”.

Holmes was then suspended in May with two senior staff after Greater Manchester Police revealed they were investigating “allegations of financial irregularities”, with the Serious Fraud Office also reportedly involved.

The Office for Students is now examining whether the university had “adequate and effective management and governance arrangements” in place. The regulator found in June it had breached registration conditions by awarding computing courses delivered by Bradford College that were “not assessed effectively”.

The university also commissioned its own internal investigation, led by PricewaterhouseCoopers. Its findings have not been shared with Sloan, who is keen to distance his college from the controversy enveloping the wider group.

In his previous role, Sloan was provost of Federation University Australia and CEO of Tertiary and Further Education (TAFE).

This left him “very much in the middle of the bureaucracy of being in a university”, so he is “grateful” now to be “at arm’s length” from that world.

“I don’t envy not knowing what’s going on… I’ve got so much to do here,” he says.

But he is not entirely disentangled from it, as his college board must gain approval from the university group for its decisions, including their annual budget.

Financial turnaround

In the year to July 2024, the university group racked up a £4.1 million deficit, and its college a £864,000 deficit, the latter being partly blamed on “market-fuelled staff shortages and spiralling agency costs”. The college also has a £6.6 million loan for building works, and in February its audit committee raised concerns over potential funding errors in a learner recruitment audit.

Following a meeting with the Department for Education, Bolton’s financial health was re-audited from ‘requires improvement’ to ‘inadequate’.

Determined to be “transparent” about their challenges, Sloan invited the FE Commissioner’s team in to provide governance support and conduct a health check.

He “enjoyed working with them”.

“As long as you’re clear around what support you want and don’t need… then we create boundaries,” he says.

The college’s financial fortunes have turned a corner since then, with a £2.2 million surplus delivered last year and the same forecast this year.

This is partly thanks to a smaller reliance on external agency staff. The group created a subsidiary, Bolton Talent Solutions, which provides 85 per cent of the college’s agency workers. It had an average of 111 in-house agency staff last year, almost half of whom have since become college employees.

The subsidiary means the group can do its own staff vetting, without paying hefty £6,000 finder fees. Agency spend dropped from £4.2 million to £2 million last year, with Sloan targeting £1.7 million this year.

The change agent

Sloan sees himself as a “change agent” and a “driver to get the best”.

NMIT moved from 13th out of 16 colleges to first in New Zealand’s league tables, and in Australia, his university moved up from eighth to third during his tenure.

He is now determined to make his college “somewhere where people say, ‘if we’re looking for exemplars of good practice, let’s go to Bolton’.

He has put a focus on “continuous improvement”, creating “performance panels” and a new quality assurance framework. Several courses have been placed on “notice to improve” – “not because they’re poor”, but because “quite good” is “not good enough”.

He faced some kickback from staff to his restructuring reforms Down Under, but in Bolton, he says despite introducing “lots of change you would think would put pressure on people, they’re all up for it”.

Whereas Ofsted last year found “low morale”, a recent staff survey found 96 per cent of staff were proud to work there. Two recent pay awards have presumably boosted goodwill.

But Bolton still struggles to find construction, English and maths teachers, and quality in English and maths is “a challenge” for which it is “trying tactic after tactic”.

“At least we can demonstrate to Ofsted that we’re not sitting on our laurels,” says Sloan. “But you can’t tell us what the silver bullet is, so we’re just doing lots of trial and error.”

Tactics include creating an English and maths facility inside the college’s construction area to prevent “leakage” of students heading to the café instead of their next class, with each subject area having its own linked maths and English teachers who then become “more au fait with the subject area”.

Mock exams have been introduced for students not taking November resits, and an advanced practitioner is being recruited as a mentor for maths teachers.

Sex, drugs and rock’n’roll

Sloan advocated for the importance of English and maths in Australia and New Zealand, where the subjects were not treated as conditions of funding as they are here.

Likewise for tutorials in “sex, drugs, rock’n’roll and financial understanding”, but “bloody hell, did we need them”, he says.

Sloan says New Zealand’s collaborative networks of colleges and universities are “not perfect”, but an improvement on our own system’s “empire-building” and “fighting for money” through bidding processes.

Sloan learned lessons in community involvement overseas which influenced how he drew together 1,100 stakeholders to create a “very much bottom-up” strategic plan for Bolton College, involving students past and present, employers, industry organisations, the DfE, Ofsted and governors.

As a result of their input, the college’s “cold and miserable” welcome area was brightened up, its wi-fi upgraded and seating areas provided for students to socialise between classes.

The college is also changing the operating hours of its outreach provision to meet the needs of parents and carers, and is looking to open for “twilight classes” to extend its teaching capacity.

Vocational value

Sloan was also influenced by how “brilliantly” 14-16 provision was done by colleges in Australia to “instil the value of vocational education as a real alternative to higher education”.

He is helping Bolton’s school heads to build a vocational ‘MBacc’ offer by opening up 14-16 provision at the college from September.

His belief in the value of 14-16 vocational education stems from how, after struggling with engagement at school, a work placement at a farm in Dumfries put him on a vocational journey which “transformed my life”.

Sloan praises his mum for having “worked like a trojan” as a nurse, barmaid and laundry maid to give Sloan what he wanted as a child, which was “everything …I must have been a nightmare for her.”

One memory that stands out for him is waking up crying at night after finding himself alone in their flat as his mum was out working. He knocked for a neighbour, who put him back to bed.

These days, he reflects how he is “ever so grateful” to his mum for how she supported him. She was the main reason he chose to return to UK shores.

True achievement

But for now, Sloan is looking ahead to the next Ofsted inspection, which will be his first in over a decade. In Australia, inspections could be undertaken remotely, with “very limited” lesson observations. Categories were limited to “satisfactory or not”, and much of the quality was measured on “learner voice”.

Bolton is now self-assessing “much stronger” than before, and Sloan is hopeful that Ofsted’s new toolkit will enable inspectors to better consider “the challenges of our local demographic”. Half his learners arrive without GCSE maths and English “so if we are actually hitting the national average, then bloody hell, have we done a great job”.

“I’m not sure that government authorities understand the complexity of what we’re dealing with,” he adds.

Bolton’s attendance is up to 87 per cent from 82 per cent last year, against a 90 per cent target. For those who are “first in family” to come to college, Sloan argues that hitting 70 per cent attendance “is an achievement”.

The week before FE Week’s visit, Bolton gave out gold stars to 420 students who had managed 100 per cent attendance in their first term (compared to 120 last year), almost half being ESOL students who are “amazing in their determination to succeed”.

One learner, “beaming” as Sloan handed him his badge, had been excluded, but was brought back in following an appeal.

This left Sloan “close to tears”. “I just thought ‘we’d written you off, and look at you now’.”

He only excludes learners as a last resort, but takes a “zero tolerance” attitude to bullying.

Ten students were recently suspended for a food fight, which left “a mess”. Cleaners were told it was their job to clean it up, which was “red rag to a bull” for Sloan. The college is investigating, and Sloan is hopeful those involved will return to classes.

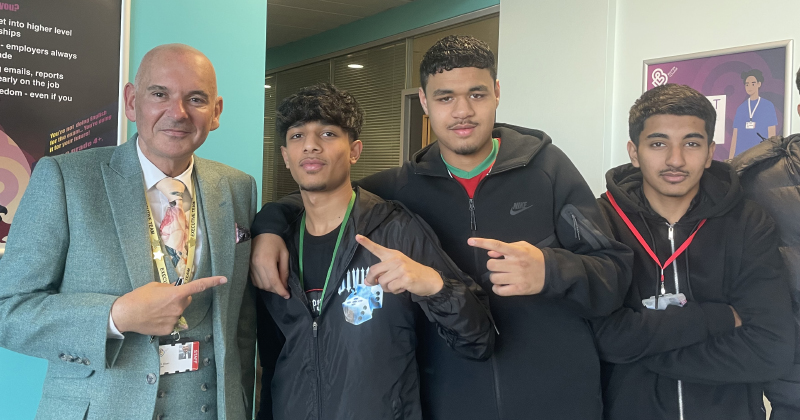

As he takes me for a tour and buys me a steak pasty from the college’s new ‘Grab and Go’ fast food café (more affordable for students than the Costa Coffee it replaced), we pass a group of rowdy young learners keen to pose for photos with their principal; he chides some of them for not wearing their lanyards.

It turns out that his morning greetings have not gone unnoticed.

“Last year we barely saw the principal, this year every morning you’re downstairs, greeting everyone,” says one. “You give us motivation.”

My family are ex students and current students at this college.

The (alleged) corruption and ‘misdirection’ of funds through the university who own the college, have no doubt done a lot of damage to the college but I’m not sure this fully explains why my family’s personal experiences have, in last few years, been so disappointing and frustrating.

There seems to be a chronic lack of funds, qualified or skilled teachers, communication, meaningful support, equipment etc etc. My older children went here years ago and it was ok but I was warned that’s it’s gone downhill and I wish I’d listened.

Those staff members who do clearly want to make a positive difference seem to be blocked at every turn. I’m sure they’re as frustrated as I am at the lack of cohesion and progress in this college.

Good luck Mr Sloan, I hope you have the stamina and the will to sort this mess out.