Sharon Blyfield, head of early careers at Coca-Cola Europacific Partners, finished her BTEC at college and rose to the top at one of the world’s biggest brands. She talks to Jess Staufenberg about the ‘employer-led system’ and the scandal of apprentice pay

Employers occupy a curious space in FE. They are the raison d’être for so much of the sector’s work – great links with employers are a key boast for any self-respecting FE provider – but they aren’t strictly in the FE sector itself.

They may work closely with training providers and colleges, but very few are training providers themselves. And yet, ministers often defer and refer to employers in speeches on skills more than to FE providers themselves.

Employers have some claim to call themselves partners, or owners, or funders, or commissioners, or customers of the FE system.

It’s not a new rhetoric. Since the 1960s, just about every government white paper has pledged to give employers a greater role in addressing the country’s deficits in technical education and work-based learning.

As Tom Bewick, chief executive of the Federation of Awarding Bodies, has pointed out before, when David Cameron announced employer ownership pilots (EOP) in 2011, an independent evaluation of the £350 million pilots over five years concluded “there is no evidence to suggest” they’d had an impact.

So we have a mixed track record on an employer-led skills system. And yet the government has doubled down, introducing ‘employer-led’ local skills improvement plans (LSIPs) overseen by ‘employer representative bodies’, while local authorities, mayoral combined authorities and FE providers have filled column inches reminding ministers to remember them too.

Surely one of the most recognisable employers in the world is Coca-Cola. Today I am sitting opposite the ball of energy that is Sharon Blyfield, head of early careers at Coca-Cola Europacific Partners, who works closely with training providers delivering apprenticeships at the company.

She’s a west London girl made good, and is disarmingly frank about the ‘employer-led’ agenda.

“From the Department [for Education], it’s all about employers and how they’re driving the agenda. And as an employer, of course we want to have a seat at the table,” she begins. “But we don’t want to be the only voice.

“We want to work collaboratively. Employers don’t want to own the agenda. They want to be a part of it.”

It’s a clear message to the government from Blyfield: don’t over-egg the employer role.

Her company is also an interesting case study in this debate, since it has a relatively small footprint as an employer in the UK: just 3,000 employees, with about 25 to 30 apprentices each year (Blyfield says they are expected to be made permanent employees, hence the small number).

But Blyfield is frank once more about the issues.

“The interesting question I always have is, who are the employers being spoken to? I say, well, no one has come to speak to me.

“Is it the employers who have thousands of apprentices? Are they the ones being spoken to? As opposed to the smaller, but big, brands like us.”

It’s a very interesting point. Coca-Cola is probably one of the only brands almost every teenager in the world would recognise, just as withdrawal rates on apprenticeships in the UK hover horrifyingly around the 40-50 per cent mark, and apprenticeship starts have plummeted in recent years.

My question is, who are the employers being spoken to?

“So it’s also about, how do they use the power of the brand?” continues Blyfield. It would make an impression with the general public if Coca-Cola were engaged more strongly, she explains.

“Although we have a small number of apprentices, if someone says ‘Coca-Cola are doing x’, they don’t necessarily need to know the numbers behind that. It’s just the fact we have the influence.”

Perhaps it reveals the problem with the ‘local’ in ‘local skills improvement plans’. If an employer has only a small local footprint – but a massive global one – then they might be overlooked in LSIP engagement.

Are certain employers, including those with vast global influence, being under-utilised?

Another reason to listen closely to Blyfield is on apprentice pay. She says all apprentices aged 16 and over at the company are paid above the national living wage that is set for adults over 23 years old at £9.50 an hour.

It’s significantly higher than the current national minimum wage for apprentices of just £4.81 an hour. Her apprentices can also expect an annual pay review and typically a pay rise.

Again, Blyfield is upfront on her thoughts on this. “If you think to yourself about social mobility, how on earth can you expect anyone to live on an apprentice wage? My one ask would be to get rid of that apprentice hourly rate. Morally it doesn’t feel right.”

How on earth can anyone expect to live on an apprentice wage?

Blyfield has fed back her thoughts to the Low Pay Commission, the independent body that advises the government on the national living and minimum wages. In April, both rates rose, as well as the apprentice rate (albeit only by only 51p).

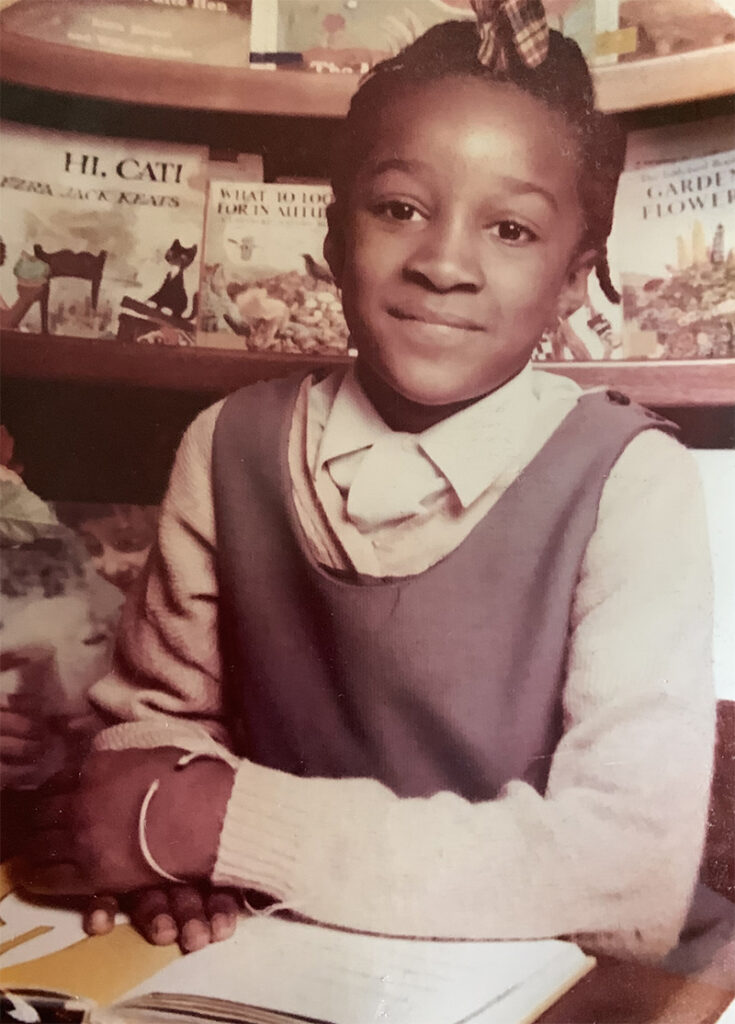

Financial instability is a reality Blyfield understands well from her own childhood. She and her two brothers were brought up single-handedly by her mum in Shepherd’s Bush in London.

Her mum worked hard to pay a small fee so she could attend what was regarded as the best school in the area ̶ a voluntary-aided grammar school.

“You had kids from very affluent backgrounds and me on free school meals. I always knew I wasn’t strong academically, so I always wanted to make it up by being the best I could possibly be.”

Blyfield also wanted to make sure as she grew up that her mum “never had to worry about money.”

Her entry route into her career was a BTEC in business and finance while studying at Hammersmith and West London College.

The course included several weeks’ work experience at a billboard advertising company and when she completed her BTEC, she was offered a job as a finance administrator.

(Meanwhile, this also explains Blyfield’s strong criticism of the government’s one-time threat to scrap BTECs. She points out T Levels are still only available in the “very niche areas” of digital, health and social care and construction, and says they are “very technical, as opposed to vocational” like BTECs.)

But it wasn’t all good news at the advertising company. During the 1991-1992 recession, Blyfield and the only two other black employees were hauled into the office together and told to pack their things.

“They said, ‘You three are going to be made redundant.’ That was one of those moments. They handled that so badly.” It looked like a targeted firing.

To Blyfield’s satisfaction, she was quickly offered an impressive sales role at Cadbury Schweppes. At the time, Cadbury owned 49 per cent of Coca-Cola and Schweppes beverages, and Coca-Cola and Schweppes owned 51 per cent of Cadbury.

In 1998, the Coca-Cola side split from the Cadbury group in the UK, and merged with Coca-Cola in the US, forming Coca-Cola Enterprises, as it is today.

“With that came lots of investment,” explains Blyfield.

Whereas previously Coca-Cola drinks had only been in licensed venues, such as pubs and clubs, and in vending machines in leisure parks and schools, now the company developed branded coolers for corner shops – enabling a big rise in distribution.

As a sales manager, Blyfield was at the front of the action. Her team told her she set “really high standards”, although she reflects she may have been “quite abrasive” as she honed her management style.

After two years she wanted a different challenge, and got an internal job as project manager for the early career journey in the company. It was the start of two decades in human resources with Coca-Cola.

In that time, she says she’s seen a shift from apprenticeships mainly for men with an engineering focus, to expanding apprenticeship programmes into sales, administration and degree apprenticeships with more women and those from minority ethnicity backgrounds enrolling.

To improve access further, Blyfield says the company removed entry requirements for five GCSEs for apprenticeships, apart from degree apprenticeships, in 2018 (FE Week has previously reported on well-known employers who set GCSE entry requirements for apprenticeships, even though this is not a government requirement).

Meanwhile, Blyfield and her team also “don’t request CVs for early career programmes. How can I compare someone who has a network and can get work experience, to someone who doesn’t? That’s just not a level playing field.” This approach is applied to all job hopefuls aged 16 to 25, so apprentices, graduates and those on the Kickstart scheme.

Additionally, checking in regularly with training providers is crucial for reducing drop-out, which Blyfield says is usually about two or three apprentices per year.

This year, mental health struggles have seen four apprentices step back. “We’ve said we’ll take you back tomorrow when you’re ready to come back.”

Blyfield picks out three training providers – Manchester Metropolitan University, the University of Lincoln and Remit Training – as examples of FE providers she works closely with across all these issues.

As she wraps up, she reiterates once more that the government should not forget where expertise lies – that is, across the whole FE system, not just with employers.

“We have our core business, while educators are the ones who are skilled in terms of delivery of skills.

“Let us be part of that conversation, but don’t put the onus on us to own it.”

The fact that there are few entry requirements shows the poor quality of apprenticeship at Coca Cola, e.g. lack of transparency and integrity. How does she decide who to take on or let go? It is all down to her personal agenda. Having said it, companies like Coca – Cola making profit from the bottom of pyramid don’t need quality staff generally. That is why she has managed to stay in such pivotal HR position at Coca – Cola for so long.