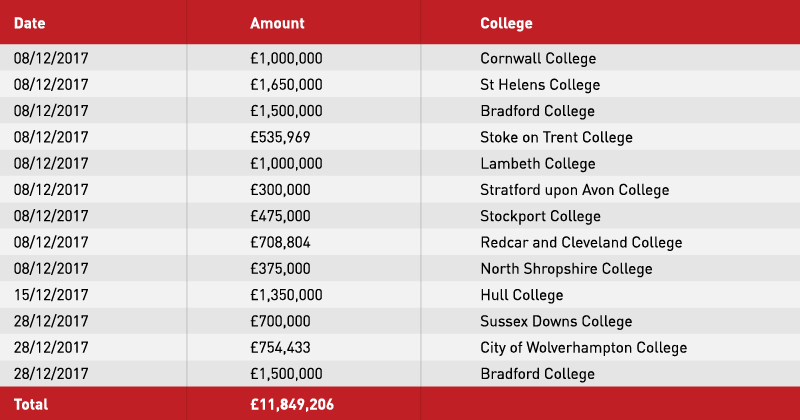

Twelve cash-strapped colleges received secret government bailouts totalling more than £11 million in December.

It perhaps demonstrates a significant increase in the amount of money being dished out to struggling colleges – and has prompted demands for greater transparency.

The figures were published by the Department for Education as part of a scheduled release detailing monthly expenditure.

“Accountability for the use of taxpayers’ money requires full and immediate transparency; there is no excuse for anything less,” said Mark Dawe, the chief executive of the Association of Employment and Learning Providers.

“It is encouraging that the FE commissioner now has a wide-ranging brief to help colleges in difficulty turn around but the funding required seems to be getting greater.”

However, Julian Gravatt, the deputy chief executive of the Association of Colleges, argued that “publishing information about exceptional financial support (EFS) at the time of need might hit confidence in a financially weak college and would not be helpful to anyone”.

He admitted that once the college insolvency regime – introduced as part of the Technical and Further Education Act – takes effect later this year it “would be worth looking again at what is published when and about whom”.

Confronted with evidence of the payments, the DfE immediately removed any reference from its monthly expenditure list, and said they would remain secret “to ensure the college’s financial position can be managed effectively during the period of support”.

“EFS funding, where appropriate, can be found in individual colleges’ annual accounts and the value of the EFS loan book is reported in the Education and Skills Funding Agency annual accounts,” a spokesperson said.

But the sums involved are unclear; the DfE’s accounts refer only to £60 million in “EFS loans” issued in the last two financial years. No figures are published for EFS grants, and Robert Halfon, when he was skills minister, told parliament in January last year that the government expected the total EFS spend to reach £140 million by the end of that March.

Described as “one of the most significant risks” to its budget, the ESFA’s accounts to March 2017 refer to the “declining financial health of the FE sector” which is “leading to greater demand for intervention and growing pressure for exceptional financial support”.

Accountability for the use of taxpayers’ money requires full and immediate transparency; there is no excuse for anything less

EFS – which can come in the form of a grant or a loan – is only available to colleges that are “encountering financial, or cashflow, difficulties that put the continuation of provision at risk”, and which have “exhausted all other options”.

The government has indicated that these bailouts will be phased out with the new FE insolvency regime later this year, proposals for which are currently under consultation. EFS is not the only area of college finance attracting transparency concerns.

FE Week has previously reported on a number of struggling colleges receiving multimillion-pound bailouts from the £700 million restructuring facility, which is intended to help colleges pay for any post-area review changes they can’t afford themselves.

These include £25 million for Lambeth College, and an as-yet unknown sum being negotiated by Cornwall College – neither of which have immediate merger plans.

During a Commons select committee hearing last month, Halfon asked the FE commissioner Richard Atkins about the lack of transparency surrounding the restructuring facility.

“I don’t have responsibility for allocating those funds,” Atkins said, adding: “I would argue, as I do whenever I intervene in colleges, that openness and transparency is really important in running any organisation. And indeed, one of the things I find in the colleges I intervene in – not always, but often – there’s a lack of openness and transparency.”

Read more: Bradford College bailed out twice in one month

Read more: Stoke on Trent College received half a million bailout

What happens when the bailout tap runs dry?

Even as the huge sums of money flowing into failing colleges have been uncovered, the government is consulting on its proposals for a college insolvency regime.

Legislation introduced as part of the Technical and Further Education Act 2017 created a new education administration, which is designed to allow colleges to go bust while also protecting the needs of the learners.

The consultation, which opened in December and closes on February 12, focuses on the technical details of the process by which a college can be declared insolvent.

Once the regime comes into effect – and it’s expected “late 2018”, as some of the details require secondary legislation – colleges will no longer have access to exceptional financial support.

Among the issues being discussed are how the DfE and the ESFA can strengthen intervention for colleges at risk of financial failure.

In addition to the existing ESFA process, the FE commissioner’s remit was recently expanded to include diagnostic assessments at colleges showing early signs of problems.

But the consultation asks for views on how “monitoring and intervention can be further improved” and how the ESFA and the FE commissioner can “work with and support colleges to help them self-identify financial difficulties at an early stage”.

It also asks for views on how a proposed period of “independent business review” – to be run alongside any ESFA or FE commissioner intervention but before a college enters education administration – might work.

The review, which the document says is “standard practice in most insolvencies of a reasonable scale”, might be triggered by a “breach of covenant or an unanticipated funding need”.

Local and combined authorities and local enterprise partnerships are among the stakeholders who would be consulted during the review, which would take between six and 10 weeks.

Emergency funding may be given to the college “if it is required to protect learner provision during that period”, though “ideally” the review would take place before such cash was needed.

Other questions in the document relate to the technical details of the insolvency itself, including whether there should be any “specific modifications” to normal procedures “to apply them effectively to FE bodies”.

A college would only enter education administration by order of the education secretary, if administration were the “best solution” to protect the learners’ interest, if it were “insolvent (or likely to become so)” and if “no other form of intervention might help the college’s long-term future”.

“We expect such scenarios to be rare”, the document admits.

In an interview with FE Week in November, the FE commissioner Richard Atkins said that while it was “definitely possible” that a college might go bust in the future, “I don’t think that’s the same as the college closing its doors to students”.

He expects his team to be called in to carry out a structure-and-prospects appraisal, which could lead to another institution taking over.

“It would be extremely uncomfortable for any principal or chair of a governing body to be declared insolvent. I’m hoping we never get to that point,” he said.

“I’m hoping this period of independent business review will bring everybody to the position of understanding what needs to happen to secure the future of that college for the benefit of the learners and the community.”

One rule for the public sector – another for the private sector

Poor management and leadership should be a reason to waste more and more taxpayers money.

Pretty disgusting really.