MPs were “misled” in Parliament by the skills minister Anne Milton today, after she claimed apprenticeships are “no longer offered” by Learndirect.

The minister was grilled by Labour’s Wes Streeting on the controversy engulfing the nation’s largest FE provider, which is increasingly seen as being offered highly preferential treatment by the Department for Education.

Even though Learndirect was labelled ‘inadequate’ overall by Ofsted in a report belatedly published last month, it has not had its government funding pulled by the Education and Skills Funding Agency as would be usual in such circumstances.

Addressing the House of Commons during education questions this afternoon, Mr Streeting asked Ms Milton about the situation.

“Last month, following unprecedented and thankfully unsuccessful legal action to prevent publication, Ofsted was able to publish its damning report into Learndirect,” he said.

“Given that other FE providers in a similar situation might have seen their contracts terminated, is the minister really comfortable with handing over £45 million of public money to a training provider that has been deemed ‘inadequate’ in terms of outcomes for learners?”

He added: “What message is she going to send to learners and when is she going to get her eye on the ball?”

Ms Milton replied: “I take exception Mr Speaker to the honourable gentleman for suggesting that I don’t have my eye on the ball. I most certainly do.”

“If any provision is judged to be ‘inadequate’, then we will take action to protect learners,” she added. “In this case, the provision judged as ‘inadequate’ by Oftsed – apprenticeships – is no longer offered by Learndirect.”

The provider has not, however, had its apprenticeships contract terminated; in fact, the ESFA is allowing it to continue until July 2018 with no early termination.

In effect it will still train and receive funding for apprentices until that time.

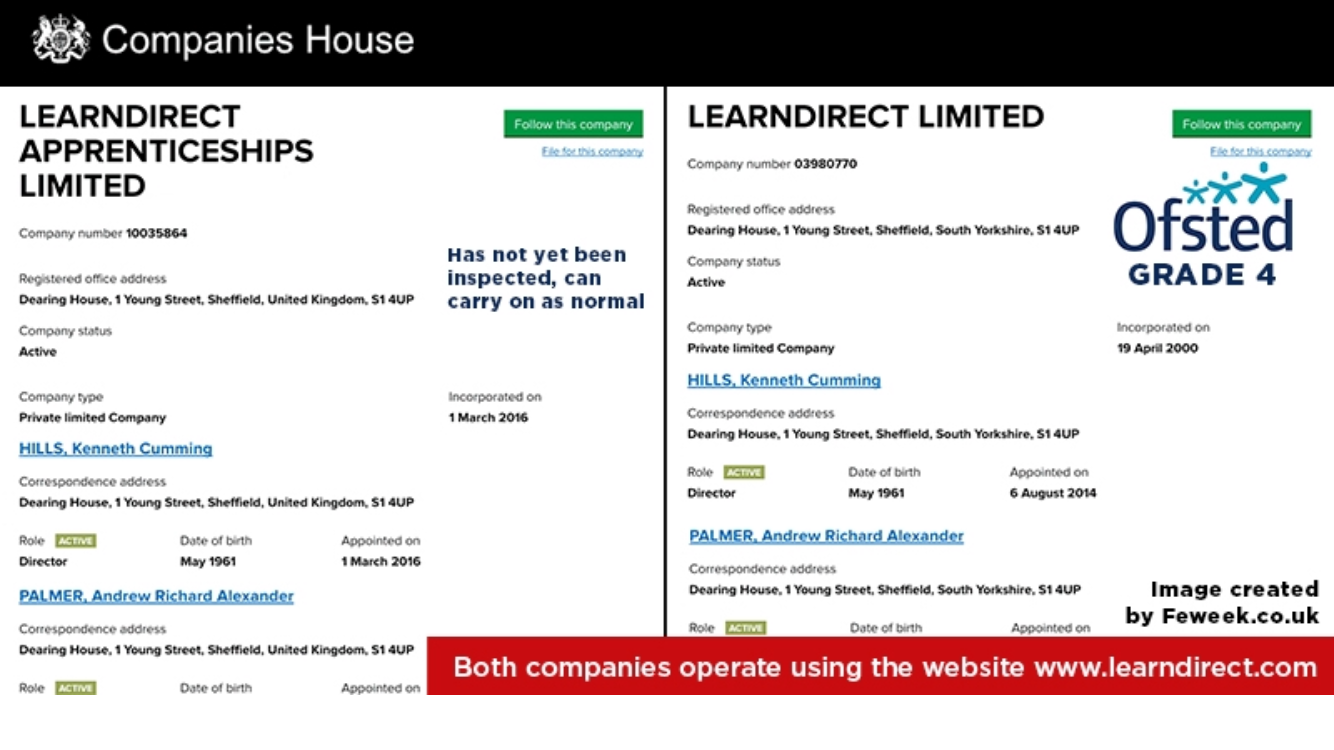

In addition, Learndirect Ltd attempted to sell its apprenticeships division last year, and via Companies House incorporated Learndirect Apprenticeships Ltd to allow for this.

The sale did not go through, but the new company successfully made it onto the new register of apprenticeships training providers in March 2017.

This means it is free to run as much funded apprenticeships provision as it wants, as this entity was not technically inspected by Ofsted.

Mr Streeting (pictured) spoke to FE Week this evening about his anger at Ms Milton’s comments.

“I think it’s pretty clear that the minister has mislead me, but more seriously, misled the House of Commons in response to the question I posed earlier,” he said.

“I think it’s pretty clear that the minister has mislead me, but more seriously, misled the House of Commons in response to the question I posed earlier,” he said.

“The central charge that I levelled at Anne Milton was that she and the government didn’t have their eye on the ball. Well, it seems that in not knowing the facts in answer to my question that accusation is absolutely justified.”

“Given the damning Ofsted verdict, damning for apprenticeships but also damning – as I said in the chamber – damning more broadly in relation to outcomes for learners, I think there are serious questions to answer about why so much public money is still being pumped into Learndirect.”

He insisted Learndirect should be at the “top of political agenda” as “lots of learners are being badly failed by the country’s largest training provider”.

Labour’s shadow skills minister Gordon Marsden also weighed in with criticism.

“Both in her apparent factual inaccuracy as to what the current state of Learndirect apprenticeships contract is, and her worryingly complacent and bunker mentality over Learndirect, the minister is showing she’s learning badly on the job,” he said.

“What she should be doing is having a vigorous immediate scrutiny of all aspects of Learndirect apprenticeships.”

Learndirect Ltd will receive up to £30 million between now and July 2018 for their current apprentices.

Contrary to Ms Milton’s claims, Learndirect itself chose to switch new recruitment to Learndirect Apprenticeships Ltd prior to the Ofsted inspection in March, and has already taken on over 3,000 apprentices since May.

FE Week has invited the DfE to respond to criticism that Ms Milton misled parliament over Learndirect today, with no response at the time of publication.