The move towards greater employer involvement in FE and skills is gaining momentum. But with employer providers having come in for less than inspiring Ofsted gradings of late, should we be questioning the wisdom of such a shift?

It’s just over a year ago that former Dragons’ Den investor Doug Richard (pictured left) said apprenticeship funding should go straight to employers, who can spend the money on training as they see fit.

His recommendations prompted a government review that Skills Minister Mathew Hancock indicated would conclude in his favour.

And that came before Chancellor George Osborne, in his Autumn Statement, confirmed employers would be directly funded for apprenticeships through Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs.

Is it really realistic for employers to drive development and delivery of apprenticeships?

Just last month too, BAE Systems group managing director Nigel Whitehead (pictured) said employers should be more involved in the design of qualifications, after all, they know what they require of learners.

Even without mention of the government’s Employer Ownership of Skills (EOS) pilot and the recommendations of Labour’s Skills Taskforce, it is safe to say there is cross-party agreement that employers should be more actively involved in the training of tomorrow’s workforce.

But is there a warning in the business philosophy of the late Apple chairman and chief executive Steve Jobs? He is said to have been of the opinion that it was better to do one thing well than to do dozens of things poorly.

Is Kwik Fit, for example, better off repairing cars and vans than thinking about how best to teach apprentice mechanics English and maths?

Or would it be wiser for G4S to concentrate on fulfilling its security contracts instead of developing the latest apprenticeship framework?

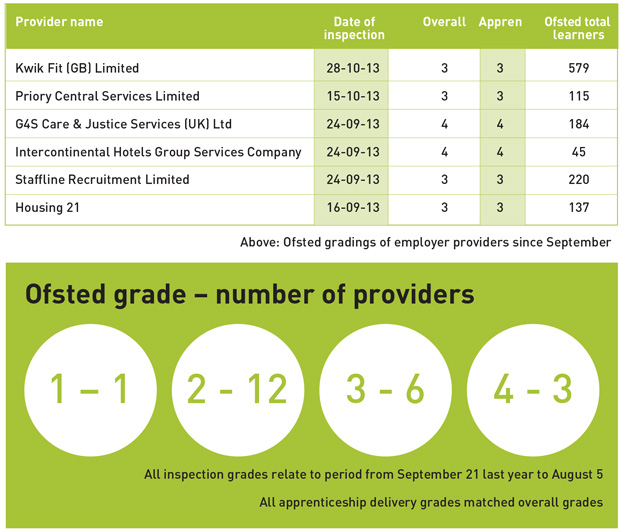

And the results of Ofsted’s six employer provider inspections since September are a cause for concern about quality as the FE and skills sector heads towards (EOS).

Government contractor G4S Care and

Justice Services and Intercontinental Hotels Group Services Company, which incorporates Crowne Plaza and Holiday Inn among others, were branded inadequate, while Kwik Fit requires improvement, as do Priory Central Services Limited, Staffline Recruitment Limited and Housing 21. The overall grades reflect the respective ratings on apprenticeships delivery.

That’s nearly 1,300 learners whose training is less than good.

Phil Hatton (pictured below), learning improvement consultant and former Ofsted inspector, said: “Writing qualifications and training materials well, to reflect employer needs and to give transferable skills, is not as easy as many obviously think, nor is delivering the training effectively.

“Given that the government will also want maths and English included, and schools have only 60 pass rates for GCSEs, is it really realistic for employers to drive development and delivery of apprenticeships?

“Kwik Fit clearly know its business well, but has just dropped from outstanding to requires improvement, yet it would be a key employer in developing qualifications for its industry — one which includes many smaller employers who will not have the experience of delivering training.”

Terry Barnett, managing director of Hawk — the first grade one independent learning provider under Ofsted’s current inspection regime, said: “This [EOS] could be devastating. Somebody needs to blink — the baby is about to be thrown out with the bathwater and the plumbing, too.

“It could create a situation that would take a decade to sort out. Lots of people out there don’t want this — the system’s not as broken as people think it is.”

It’s a concern not lost on Association of Colleges president Michele Sutton (pictured right). Opening the association’s recent annual conference in Birmingham, she said: “If we compare this year’s marked improvement for college Ofsted outcomes, to some employer-led apprenticeships outcomes, I think there should be some questions to ministers around the fitness for purpose of some large employers to be a lead position in the new employer-led landscape.”

But there is interest in getting involved in skills from the business community.

Neil Carberry, Confederation of British Industry director for employment and skills, said: “The idea you can meet the apprenticeships challenge without businesses themselves ensuring the training is commercially-relevant to the firm is a fallacy.

“The way to do this is by giving employers the power to procure high quality training through a vibrant and well-regulated market. A command economy, driven by the government, won’t raise standards.”

And Alexander Jackman, head of policy at the Forum of Private Business, said: “The Ofsted results may well be indicative of some of the larger employers.

“But I would like to think that the smaller ones, who are doing things on a much smaller scale, are able to offer something a little more bespoke. They too need government support in this area.

“Employers know best what skills gaps they have in their organisations so the movement towards funding them directly is the right one.

“However, this is a big shift in how funding works so the EOS will take time to get right.

“We would ask that government continues to support businesses to make sure they adapt to the new system and make it a success.”

And it would be unfair to tarnish all employer providers with the ‘less-than-good’ brush.

After all, before September there were a dozen good ones, plus an outstanding one, dating back to September last year (although there were a further six grade threes and three more grade fours).

And in the UK Commission for Employment and Skills, it seems EOS has powerful friends.

So where does that leave us? Only time will tell, but if the experience of Mr Hatton — joint author of the first NVQ — is anything to go by, then caution is needed.

“Back in 1987 when the first NVQ was being developed the first attempts written mainly by employers were all over the place and rejected as not fit for purpose,” he said.

_______________________________________________________________________

Do employers even want to take ownership of skills?

There are three big problems with the government’s plans to give more responsibility for the skills agenda to employers — also known as employer ownership of skills (EOS for short).

The first is the assumption that employers actually want to take ownership of skills. Pilots overseen by the UK Commission for Employment and Skills suggest they do.

But the funds involved are small compared with the overall skills budget, and only a tiny minority of employers have got involved so far.

The majority of employers — especially small firms — have stayed away in droves. Given the choice, I have no doubt that most businesses would prefer colleges and training providers to carry on managing both the funding and the form-filling on their behalf.

It’s worrying that in September and October six successive Ofsted reports produced grade three and four results for employer providers

Second, employers that contract directly with the Skills Funding Agency to deliver apprenticeship training don’t always achieve outstanding results.

It’s worrying that in September and October six successive Ofsted reports produced grade three and four results for employer providers.

Third, apprenticeships are meant to be a three-way partnership. Employers get people with skills to do jobs right here, right now. Apprentices get that too, plus transferable skills, knowledge and experience to help them move up the career ladder. The tax-payer gets a skilled workforce which boosts productivity and GDP.

By putting one of the partners in the driving seat, EOS risks silencing the voice of the apprentice, and ranking short-term employer interests over the long-term interests of the economy as a whole. And that would be a real mistake.

David Harbourne, director of policy and research, Edge Foundation