ENGINEERING STAFF RECRUITMENT EVENT THU 27TH MAR

5.30PM – 7.30PM

In the frame for special commendation for video on local policing

Television and film students found themselves in the frame for high praise after filming and editing a video to boost confidence in local policing.

Five level two students at Darlington College worked on the video, which features officers giving out crime reduction advice and helping reduce antisocial behaviour through high-visibility street patrols.

Senior officers were so impressed with the results that the students received a superintendent’s commendation — an accolade normally reserved for non-police officers who show outstanding bravery to prevent crime or protect others.

Durham Chief Superintendent Graham Hall said: “We have been trying to engage with the public to get our messages over and we are delighted with the work the students have done to achieve this.”

Course tutor Mike Chapman said: “There is no substitute for working to real-life pressures, having a client to please — so this has been an incredible learning experience for them.”

Visit www.youtube.com/watch?v=w0oLK_3XGyI to view the video.

Cap: Students Reece Nash, Aidan Fisher, both aged 19, Aaron Ball, Danielle Jameson, both 18, and James Liddell, 19, with Darlington neighbourhood inspector Mick Button (left) and Chief Superintendent Graham Hall

Is FE and skills on board the Lep drive and does it even need to be?

Local enterprise partnerships seemed to be the next big thing for FE and skills in late 2012 when Lord Heseltine called for a single funding pot that included the adult skills budget.

Fears emerged that a lack of FE and skills representation among Lep boards might see sector cash used elsewhere, on infrastructure projects, for instance.

But with Chancellor George Osborne having announced his own take on Lord Heseltine’s proposals, with a smaller amount of sector cash up for grabs,

FE Week reporter Paul Offord looks at whether fears should remain about who fights the FE and skill corner at Leps.

There were raised eyebrows when Tory grandee Lord Heseltine called for control of the entire skills budget to be passed from the Skills Funding Agency to local enterprise partnerships (Leps).

The former deputy prime minister’s report of late 2012, No stone unturned in pursuit of growth, suggested that £17bn of skills cash over four years from 2015 should go directly to Leps.

The concern was that skills cash, without the protection of ring-fencing could go, for instance, towards infrastructure projects instead.

The only protection for the skills agenda, it seemed, was a strong sector proponent on the Lep board, but an Ofsted survey and report in March last year warned: “FE remains under-represented at the highest strategic level on Lep boards.”

It added: “The majority of Leps were not sufficiently well informed about learning and skills provision in their area.”

But when Chancellor George Osborne said he would be implementing Lord Heseltine’s idea, what emerged was an annual Single Local Growth Fund of just £2bn.

Handing over the entire skills budget had been rejected in Mr Osborne’s 2015/16 spending review, although included in the new fund would be almost all cash available to FE providers for capital spending projects (around £330m a-year).

It will mean, for example, that colleges will have to apply to their Lep, instead of the agency, for money to build most new training facilities.

The agency confirmed it would still distribute a “small” additional capital spending budget to providers — but declined to comment on how much money would be involved.

Meanwhile, control over the spending of £5.3bn up to 2020 from the European Union structural and investment funds will also be handed over to Leps.

The funding has to be spent on business, transport, environmental, or education and training projects that help drive regional development and FE providers can apply for a share.

So, while the Leps project isn’t on the scale imagined by Lord Heseltine, they will nevertheless have control over FE and skills pursestrings.

With that in mind, research carried out by FE Week has shown that many Lep boards have little or no representation from the sector.

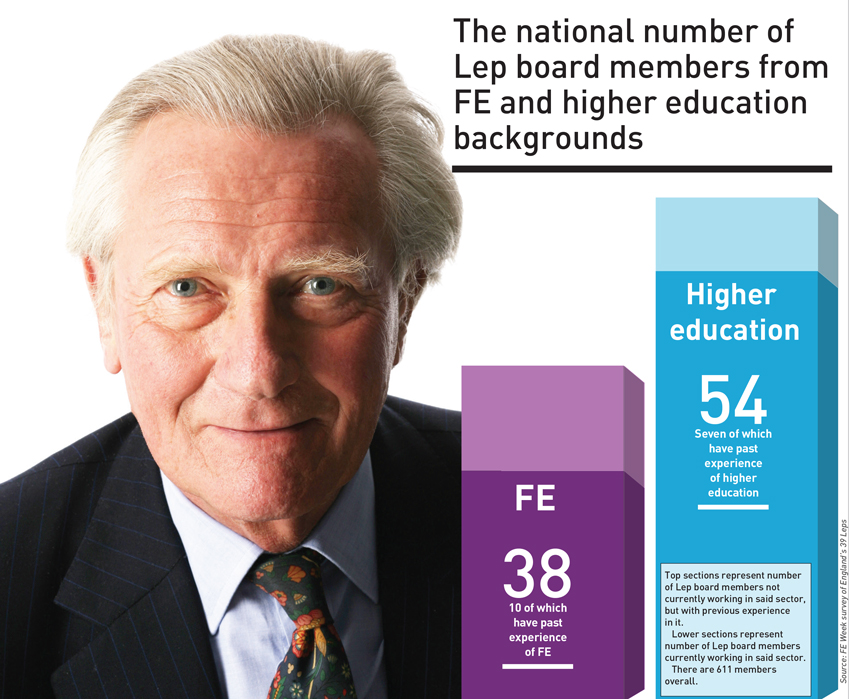

Just 28 (5 per cent) of the 611 members of all Lep boards were currently involved with FE, while another 10 (2 per cent) had past experience of the sector.

It compares to 54 board members with present or past higher education experience and 14 with current or previous links to primary and secondary schools.

And we found that 14 Lep governing boards had no FE representation at all.

The findings follow a call by Oftsed (in its 2012/13 annual report on FE and skills) for “more support” to be shown to FE by Leps.

Dr Ann Limb OBE, chair of the South East Midlands Lep, was principal of Milton Keynes College from 1986 to 1996 and Cambridge Regional College from 1996 to 2001, before moving to the charitable and private sector.

She said: “It is definitely a very good idea to have FE fully engaged with Leps. There are a number of ways they can do this — and one of those is through participating in board meetings.

“Another way of improving FE influence on Leps can be through some kind of skills and employment committee, which we and many other Leps already have.

“We have representatives on ours from all nine FE colleges in our area and one sixth form college. They all work well together through the committee which helps with strategic planning.

“They all did a brilliant job of drawing up our skills plan for the next three to five years and the main Lep board approved it.”

Dr Limb explained the committee elects one of its members to represent it on the board.

She said: “It happens to be someone from higher education at the moment [vice chancellor of the University of Northampton Nick Petford] but it could just as easily be someone from FE.

“There might be some scope for reserving a place [on the main LEP board] for someone from FE, as well as someone from higher education, but there is the danger of the board becoming too big and meetings too long and inefficient — which board members from the private sector in particular would not approve of.”

Skills Minister Matthew Hancock had also said in December 2012 that Leps would be given “sign-off” on granting colleges and training providers Chartered Status.

But the quality mark has still not been introduced and the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) said there were now no plans to ask Leps to approve applications.

A BIS spokesperson further confirmed it was encouraging all Leps to have college representatives on their boards.

But he added the final decision on board membership would remain with individual Leps and minimum quotas would not be introduced.

He said: “The government gave Leps a new role setting local skills strategies. To that end, each Lep will be encouraged to have a seat on FE colleges’ governing bodies with colleges also represented on Lep boards.

“Leps are business-led partnerships whose activities are driven by local economic circumstances and priorities. They themselves are best placed to identify the most appropriate representatives to sit on their boards.”

David Hughes, chief executive of the National Institute of Adult Continuing Education, said he had seen a “good appetite” from Leps across the country for “supporting” the sector.

But, he said: “The lack of FE representation on Lep boards in some areas is of concern.

“However, strong partnerships between FE colleges, local authorities and local employers predate Leps in many areas of the country and will continue to be the foundation of strong local learning and skills strategies.

“What’s important is focusing on strengthening these partnerships given Leps’ new responsibilities for learning and skills.”

Christine Doubleday, deputy executive director of the 157 Group, said: “We are, of course, concerned about the lack of interplay between Leps and FE.

“Leps have, on their doorstep, a public asset which offers them access to thousands of employer relationships and to the future talent of this country.

“An alliance between Lep chairs, FE corporation chairs and principals would be a mighty powerful force to be reckoned with.”

Lindsay McCurdy, from Apprenticeships4England, thought there should be a minimum of one FE representative on each Lep board.

She said: “FE has to be represented on them all — it’s no good someone from higher education trying to represent us. These Leps are going to be so influential on our sector and it’s important they understand how we work.”

A spokesperson for the Association of Employment and Learning Providers said: “FE and skills representation on the boards would obviously be desirable, but we know that providers are getting engaged at committee level and we would encourage more to do so.”

But business leaders were reluctant say whether or not there should be more FE representation on Lep boards.

The Confederation of British Industry (CBI), Federation of Small Businesses, and Forum of Private Businesses (FPB) all declined to comment on the issue.

The next few weeks will be vital if LEPs are to strike growth deals with government that empowers colleges and other providers to play a full and imaginative part in driving local economic growth.

It’s clear that the skills and employment plans for growth, submitted by Leps before Christmas, are a mixed bag.

Several of them would have benefitted from more expert guidance from FE representatives at Lep board level — as well as at skills and employment task group level.

Where things work well, colleges have been prepared to think collectively and imaginatively about supporting the plans.

For example, London colleges and Association of Colleges London region have agreed the secondment of a college director to work with the London Lep on its growth deal.

But where there has been poor engagement, the plans submitted are likely to lack rationale or supporting evidence and be confused about funding, programmes and what, if any, flexibility is required.

If we get this right, there will be opportunities to make a huge difference, but the challenges are big and the timescales short.

Leps often have laudable ambitions for skills — some plans will for example incentivise local careers guidance partnerships and FE/higher education collaboration, which opens routes for young people with local employers into higher skills roles in key industrial sectors.

But Leps need FE and skills expertise in order to draw up properly evidenced, realistic and imaginative plans.

It’s not easy when a university vice chancellor is asked to represent higher education, FE, skills and apprenticeships on a Lep board — or when representatives from local authority economic development teams struggle towards a skills and employment plan without expert engagement from colleges and providers.

Those Leps who already get it should secure skills deals that bring benefit. Let’s see quick action elsewhere to inject FE and skills expertise to achieve deals that can stick.

Teresa Frith, senior skills policy manager, Association of Colleges

The 39 Leps are currently immersed in the process of producing and getting their strategic economic plans signed off by central government.

From what I have seen skills and employability are central to every plan.

If the upturn in the economy is to be cemented, then gaps in skill provision will need to be filled and training providers will have to find effective ways of working with business.

Leps will be absolutely central to this process, acting as an intermediary.

The question is how should FE best play into the regeneration of local economies?

Is it by trying to get a seat on the Lep board, or by showing their capability to engage, work and deliver for business and for local people? I would say the answer is the latter.

I recently met with senior staff at Burton and South Derbyshire College and was hugely impressed with their clear focus on understanding what business needed from them.

From that they continue to deliver the programmes that really benefit the community. Interestingly the conversation was not about structures, but about delivery.

The frustration that a number of the Leps feel over the current system of delivery is evident from the economic strategies.

They make the point that companies are prepared for training as long as it is the right training

The problem is that in too many cases the right training is not available or business does not know how to access it. If they cannot find it they will turn to other forms of provision, which will be increasingly through e-learning platforms.

So colleges that can gain labour market intelligence and work with employers to develop the courses they need will be well placed to prove themselves as an essential component of local economic growth.

I would argue that this is best done through a strong relationship on the ground with employers, and not by thinking that this can be achieved through simply being on the board of a Lep.

David Frost, chair, Lep Network

Putting English and maths ‘front and centre’

Among the areas of Ofsted praise heaped upon North Somerset’s outstanding Weston College earlier this year Foundation English. Dave Trounce explains how the college putting core skills at the centre of the whole college curriculum.

The flurry of excitement which greeted the post-Christmas announcement that our Foundation English programme at Weston College was deemed by Ofsted to be outstanding almost — but not quite — caused us to miss the fine details of the inspection report.

In particular, one word jumped out at — “remarkable”.

“The team has had a significant and remarkable impact on improving vocational teachers’ confidence,” it said.

The team it was talking about had only been in existence for a few months, and the inspectors were praising them like veterans of a hard-won and lengthy campaign. The truth is we’re only at the start of the journey. Even so, there is no doubt that already we are making a remarkable impact right across our college.

It seems to be a tradition among colleges that the specialist teaching of English — and maths — is hived off to individual faculties to deliver. Our ambition was different; we wanted to bring it front and centre and make it a core priority for all aspects of college provision.

Of course, there are government expectations too. It would like all school-leavers who do not have a GCSE grade C in maths or English to work towards this during post-16 studies, and from September this year it will be a condition of funding for all colleges.

Our emphasis is not just on encouraging students through qualifications, it is about supporting the curriculum areas to better enable the teaching of English and maths

A recent number-crunching exercise revealed that around 40 per cent of our students do not have A to C in English, with a slightly higher percentage failing to get the same grades in maths. This is broadly in line with the national average, but it does mean we have some real work to do.

However, ambition is one thing; getting the right teachers trained to the highest standards is another.

Our emphasis is not just on encouraging students through qualifications, it is about supporting the curriculum areas to better enable the teaching of English and maths, and about upskilling staff to really deliver these subjects.

We cannot and will not just ask anyone to deliver; it has to be a high-performing team that can work within a campus-common timetable model to contextualise English and maths for each curriculum area.

We have not been afraid to innovate and experiment. For example, learners in our creative art and design faculty have been given an ‘English diary’ which allows the student, their vocational tutor and the specialist English tutor to implement a seamless approach to English development — including a standardised marking system we feel sets a benchmark for other colleges — that is integral to their understanding of the subject.

We have also looked at collaborative models, including an embedded specialist English teacher working alongside vocational tutors in our hairdressing and beauty therapy department that has made a significant impact on learners’ progress.

Where next? Well, we’re great believers in growing our own staff and from April 30 we will be delivering an English and maths advancement programme for teachers, trainers, support workers and assessors. This will deliver levels three and five in both subjects. Also, we’re keen to implement English and maths hubs in each of our three campuses and we hope to set up such zones in the next academic year.

Ultimately, we would like to see our specialist teachers deliver GCSEs and also at level three for students who already have A to C, as part of the Technical Baccalaureate. This would stretch and challenge students who will benefit from higher level qualifications. By then, we would hope our vocational teachers are sufficiently skilled to teach English and maths at Functional Skills level.

Dave Trounce, assistant principal, Weston College

Less adult money signals a moral future

The world of publicly-financed FE is a diminishing one. Andy Gannon makes the case for defending the sector from further government cuts with a new, morality-based dialogue.

So, perhaps unsurprisingly, the adult skills budget faces a cut of around 15 per cent.

It goes without saying that this is regrettable — we all know that adult skills is a key area of work for FE, and of vital importance if we are to get more people in work and productive in their lives.

In an excellent article in the New Statesman recently, John Elledge bemoaned the lack of public outcry at this decision, but this is not news to those of us working in the sector.

Perhaps more cuttingly, he criticised sector leaders for not shouting more loudly, adopting, as many have done, the ‘it could have been worse’ line.

What such criticism fails to acknowledge is that we face a stark choice as a result of this and other recent funding decisions about the kind of sector we want to be part of in the future.

It is true that, in the past, we have perhaps tugged our forelocks a little too quickly and bemoaned being done unto, but I wonder if our current situation signals a desire that we can be at the forefront of new developments.

There have been plenty of voices recently urging the sector to be less reliant on public finance. From Vince Cable to David Russell, the message is becoming ever clearer — don’t dwell on where your money came from in the past, just go out and find some new money.

Whether it be from muscling in on apprenticeship trailblazers, embracing employer ownership pilots or actively supporting new types of school, FE leaders with a bit of nous are already ahead of the game.

The era of ‘survival of the fittest’ both financially and in terms of quality is clearly upon us

Whatever your personal view of its rights and wrongs, the era of ‘survival of the fittest’ both financially and in terms of quality is clearly upon us.

And I am sure that the entrepreneurial spirit of many FE leaders will ensure that a great many are not only very fit, but also survive into longevity.

There is, however, another side to all this. A criticism that, some would say, could more fairly be levelled at FE sector leaders is that they are obsessed with the detail of policy change.

If schools or universities were targeted, their leaders would talk as loudly about the impact on education as they would about the impact on institutions. They would not hesitate to take a moral stance on the very purpose of education itself.

It seems to me that FE talks rather more often about what we do than about why we do it — and therein lies a big difference.

I know that we have teachers and leaders who care passionately about why they go to work every day, but that part of our voice is not very loud.

I am, as yet, unsure whether that leads to, or results from, the apparent belief of policymakers that the way to improve things in FE is to constantly tinker with minutiae, rather than revisit the very purpose of the whole enterprise. Either way, it’s not healthy.

So, where adult funding is concerned, let us quietly get on with the business of making our institutions survive financially — yes. But let us also engage in some loud discussion about moral principles.

It is surely wrong for adults to have to pay for a basic level of education — let’s say up to level two — when the main reason for their not having it is failings in the school system. There is a case we can argue with conviction, not because it protects FE, but because it is morally right.

It would, at least, give us a starting point for an adult discussion that we, with justification, should be leading rather than falling victim to.

Andy Gannon, director of policy, PR and research, 157 Group

Making employers pay ‘risks’ 16 and 17 apprenticeships

A government consultation on apprenticeship funding reforms is looking at making employers pay towards training. Kirstie Donnelly explores the implications.

All 16-year-olds are different. All of them have different talents and different goals in life.

Some, for example, are naturally academic and suited to classroom learning. Others, as we all know so well, are better suited to practical learning. These are the ones who should be given the opportunity to start an apprenticeship.

So I was alarmed to learn the government’s technical consultation on apprenticeship funding, published this month, and its proposed changes to the funding of the 16 and 17-year-old apprenticeship system that could potentially undermine or severely damage it.

According to the proposals, apprenticeships for 18-year-olds would remain fully-funded (for the time being, at least), but employers would have to part-fund apprenticeships for 16 and 17-year-olds.

No decision has been taken, but as the Association of Employment and Learning Providers and others have cautioned, moving from full funding to a new approach risks apprenticeship uptake.

And it seems to me these proposals would create a two-tier system, putting apprenticeships for 16-year-olds on a different standing to those available to 18-year-olds — which is surely another way of saying that 16 and 17-year-olds shouldn’t really be doing apprenticeships in the first place, but should be staying in school.

This hardly matches the rhetoric we heard from the government during National Apprenticeship Week, emphasising the value of vocational routes.

How will we ever end what Education Secretary Michael Gove called ‘the apartheid at the heart of our education system’ if the system portrays apprenticeships at age 16 as inferior to A-levels?

How will we ever end what Education Secretary Michael Gove called ‘the apartheid at the heart of our education system’ if the system portrays apprenticeships at age 16 as inferior to A-levels?

Nobody is suggesting young people should be discouraged from academia. I just want people to have the opportunity to choose the route that’s right for them, not be pushed one way or another.

Make no mistake, this choice matters. I don’t need to tell you that plenty of 16-year-olds thrive as apprentices, and gain skills that make them work-ready — which, given the levels of youth unemployment in this country, mustn’t be undervalued. Apprenticeships are a lifeline to social mobility, and should remain so.

But I’m also worried about the impact this will have on employers — the very people we rely on to drive apprenticeships forward. My biggest concern is that if employers have to bear the cost, will they even bother to hire apprentices at this age?

And, especially if apprenticeships for 16 to 18-year-olds are to be run along different lines, are we adding yet another off-putting layer of bureaucracy? Okay, larger businesses will probably be fine, but what about small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) — the bulk of the UK business community?

A fifth of small business owners plan to take on one or more apprentices in the next 12 months, according to the Skills Funding Agency — but if the government makes the funding structure too complicated it risks jeopardising any progress we’ve made.

To me, these plans are just another way for the government to slice more funding from the FE sector, when instead they should be investing in it.

History shows us that during a recession, the companies that succeed are the ones who invest.

Investing in apprenticeships, including for 16 and 17-year-olds, will help this country come out on top.

It’s important to remember that these are just proposals. But if they do come into effect in 2016, it’ll be yet another change in a sector that is crying out for stability.

I think it’s fair to say that at the moment, apprenticeships don’t have the credibility they deserve. In fact, we haven’t had a vocational and apprenticeship system that we could be truly proud of for more than 30 years. Get the system wrong now and we risk years’ more upheaval.

Our apprenticeship system has the potential to benefit so many, but endless tinkering, and no farsighted consideration of the consequences will only damage it in the long run. Far better that we choose the right approach now and focus on making it great.

Kirstie Donnelly, UK managing director, City & Guilds

Graham Stuart, chair, Education Select Committee

After almost four years at the helm of the House of Commons Education Select Committee, Graham Stuart is not known for holding back when it comes to criticising government.

But the Tory politician’s willingness to speak his mind in his committee sittings should not be mistaken for an absence of party loyalty.

Pro-austerity and highly critical of the opposition, Stuart is undeniably a Conservative, with a big “C”.

The 51-year-old MP for Beverley and Holdness, a constituency in Yorkshire where he won a seat for the first time in 2005, cannot hide his disappointment at not having made it to the ministerial ranks after the 2010 general election, but still sees himself as a contender, maybe even for Secretary of State.

Reading literature from “totalitarian countries” in Eastern Europe and Asia had, by the time he finished sixth form, given Stuart a “deep dislike of ideologies which oppressed, suppressed and minimised the value of the individual”, he says.

After entering politics in Cambridge as the first Tory city councillor elected in six years in 1998, Stuart took on an additional voluntary role at a local school which would seal his interest in education forever.

It suits our opponents to make out we are the most heartless bunch of ideological cutters who do it for the sheer hell of it

“When I was a councillor, I became chairman of governors of a struggling junior school,” he says. “I found my involvement there, working with other government, hiring and then supporting a head to turn the school around, one of the most satisfying thing I have ever done.

“It’s a cliché, but as Disraeli said: ‘Upon the education of the people of this country, the fate of this country depends’, something like that — and that remains true. What else can you do in politics that will have such long term consequences? And you just hope that your involvement has positive consequences.”

Stuart is relentless in his dislike and mistrust of the left, possibly something to do with the fact that, having started his own publishing business while at university (and failed to get a degree in the process) he is exactly the sort of self-made success, bootstraps and all, that conservatives would like to see every man and woman aspire to be.

He is quick to chastise Labour for its opposition to the government’s austerity programme, which he says is too slow.

He says: “We have talked about the need to balance the books, and we have moved in that direction, which is commendable, but we are moving there remarkably slowly.

“At the same time it suits our opponents to make out we are the most heartless bunch of ideological cutters who do it for the sheer hell of it, out of some weird, small-state obsession rather than the simple arithmetic of the fact that if you spend more than you have coming in you create a burden for the future — and with an ageing population, the dynamic presence on the world scene of the likes of China, South Korea and India, there is nothing obvious to suggest that we have such a golden future that we can afford to burden our children and grandchildren with monumental levels of debt.”

He says his support for the FE sector is perhaps buoyed by his admiration of outstanding colleges in and around his constituency, but he says more work is needed to allow the “Cinderella service” to thrive.

He says: “I am rather spoilt by the quality of FE provision in my area, but it also contributes to my having perhaps an unusually positive view of FE and what it can do. I think FE is fantastic and needs to be more celebrated, more recognised and I hope that can happen over time. But right now, those three institutions are doing a great job, and are doing so with a pretty high degree of self-confidence, and success.

“So, equally, whatever our complaints about government policy and financial challenges, just in my immediate area are three excellent institutions doing a damn good job — which is to be celebrated.”

He adds: “One of my top priorities is to press for improvements in careers advice and guidance in schools. It is nothing short of a scandal that so much of it is so poor. We have got more complexity in choices within education than we have ever had before in history.

“You cannot intuitively understand the labour market any more, and there is no big employer down the road. It is more complex and more opaque to a teenager than it has ever been — and therefore the role of careers advice and guidance is critical, and the FE — as a bit of a Cinderella service, sadly — is hidden.

“The benefits that FE can offer young people is hidden from too many of them by a failure of quality provision in careers advice and guidance, by vested interest deliberately blinding young people to alternatives to the institution they are currently in, and also there are other issues.”

Stuart makes no secret of his ambitions for higher office, and says his decision to run for the chairmanship of the committee came after he, like many other Tory hopefuls, missed out on a ministerial post after the 2010 general election.

“I [had] got involved in the children, schools and families committee,” he says, “so I sat on that the whole time that department existed, under Barry Sheerman’s chairmanship, and then we had the general election, we had the coalition, and David Cameron didn’t make me a minister, and I duly put myself forward for the select committee.

“With the coalition, and 25 of my colleagues who had already served as shadow ministers losing their jobs, now I recognise that [although] I had always imagined that I would be a minister, if that’s not to be, it’s not to be.

“If David Cameron asked me to be a minister I would happily serve.”

He also leaves his future as a possible successor to Education Secretary Michael Gove in the Prime Minister’s hands, but adds: “Obviously education is of massive interest to me, but the longer I do this, the less certain I am about so many things.”

——————————————————————————————————————————————

It’s a personal thing

What is your favourite book?

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. It goes back to my sixth form reading.

It is a very slim, delicious volume on surviving Soviet labour camps for a day, which then led me to reading The Gulag Archipelago one and two with endless listing of the endless numbers of people killed by socialism in Stalinist Russia

What do you do to switch off from work?

I cycle, and before I smashed myself up skiing last year, I occasionally did triathlons. I did a half Iron Man three years ago. I was, last year, going to be doing some pretty heavy cycling. That would have got me fit, but as it was I was in a hospital bed with my smashed-up chest, pelvis and then, eventually, other problems from that

What did you want to be when you grew up?

Probably something to do with sport, playing rugby for England or similar, or football, even though I didn’t play football at school. I had a toy tractor as a child, and I was so keen on it that I insisted I was to be called Tractor Man

What’s your pet hate?

I don’t have one

Who, living or dead, would you invite to a dinner party?

Giovanni Falcone, Varlam Shalimov, Penelope Cruz and Victoria Wood

What the budget means for FE beyond the apprenticeship headlines

The extension of the apprenticeship grant for employers may have provided the main source of budget attention for FE, but Mick Fletcher looks at how else the sector might have been affected by Chancellor George Osborne’s announcements.

In a pre-election budget, designed to win votes through devices like cutting the bingo tax, FE was never going to feature strongly and, sure enough, it scarcely featured at all.

It’s true that the chancellor talked of boosting apprenticeships — something that is always good for a round of applause — but the so-called ‘boost’ consisted only of keeping the existing grant for those small and medium-sized enterprises that take on younger apprentices and meanwhile the Education Funding Agency gave the game away by planning for fewer numbers in 2014-15 than in the current year.

To assess the real implications for the sector one has to look beyond the headlines.

Rather than looking for what the chancellor said about FE institutions directly it might be better to look at what the budget, the autumn statement and the associated economic outlook means for actual and potential students — what is the indirect effect?

The picture is relatively clear, if bleak.

Despite welcome signs of an economic upturn in some sectors there will be a continuing squeeze on real wages; the key measure of GDP per capita will not return to pre-2008 levels until at least 2017.

At the same time there will be a continuation of deep cuts in the safety nets provided by the state affecting those in and out of work.

Colleges will need to focus more on how to help people to pay for learning rather than helping them avoid paying

Although there is an increase in private sector jobs a high proportion have been part time and temporary, and outside London overall employment growth remains weak.

Youth unemployment remains stubbornly high and would be higher still if 16 year old Neets had not been relabelled as truants, making them, and not the government, appear responsible for their fate.

The major implication of this is that the need for FE will grow at the same time as the ability of individuals to access it will diminish.

Improving their skills is the best way for individuals to escape insecure employment, but state subsidies for anything beyond the most remedial types of education are set to reduce and possibly disappear.

Colleges will need therefore to focus more on how to help people to pay for learning rather than helping them avoid paying.

It means making imaginative use of loans, which up to now some institutions have effectively ignored, but also challenging policies that deny adults the ability to access learning in small, affordable bites.

It means thinking about affordability in FE in the way in which the sector has embraced that concept when delivering local, accessible HE.

Interestingly the budget included a dramatic relaxation of the rules around the use of pension funds making it no longer mandatory to buy an annuity and trusting individuals to plan their finances.

In the same spirit it might be time to revisit the idea of allowing individuals to access part of their pension before they retire to fund retraining a or a change of career direction.

Proposals for apprenticeship credits and childcare credits delivered through dedicated accounts suggest that it may be worth looking again at ideas around learning accounts as a means of supporting individual investment.

The more favourable treatment of older people should lead FE strategists to think again about how to encourage inter-generational transfers to support learning.

Adverse circumstances are a spur to creativity and the next few years may well see such imaginative new ways of making FE accessible.

These new ideas however, and the detail of funding agency policy, should not be allowed to obscure the big picture.

Strategic leaders will need to address the implications for their institutions of a future in which much of FE is no longer seen as a public service, but as a private good; in which demand is potentially strong but increasingly instrumental, and affordability for low paid workers is key.

Mick Fletcher is an FE Consultant

Keeping the options open on Functional Skills

The government has already downgraded Functional Skills more than three years before they are fully replaced in the apprenticeship programme by GCSEs. Roger Francis makes the case for viewing the qualifications as equal again.

Few people would deny that the UK faces a huge skills crisis.

Nearly 50 per cent of the adult working population has the level of maths competency expected of an 11-year-old and probably cannot interpret their own pay packets.

Moreover, a raft of surveys last year from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development placed the UK close to the bottom of global tables for maths, English and science in developed countries.

In those circumstances, and with UK companies constantly reporting an inability to find staff with the relevant skills, it almost seems churlish to criticise a government initiative aimed at addressing the problem.

Yet that is exactly how a wide range of experts across the sector have responded to the governments’ proposal to replace Functional Skills (FS) within the apprenticeship framework with A to C grade GCSEs from 2017.

The government’s position appears to be that it wants GCSEs to be adopted as the “gold standard” and that leaving FS in a similar position would cause confusion and detract from that long-term aim.

So FS, which up until six months ago was positioned as an equal alternative option to GCSEs, has now become a “stepping stone”.

This instant downgrading appears to have taken place without any consultation with the relevant stakeholders and without any statistical analysis of the impact of FS on competency levels.

However, in setting out that strategy, I believe the government has failed to recognise the very real differences between vocational and academic career paths.

FS were developed specifically for people who chose the former. Many of the learners whom we support have already failed their GCSEs in maths and English and achieve the equivalent FS qualifications not because they are easier or because they are merely “stepping stones”, but because they are more relevant to their job roles and to situations they meet in everyday life.

The vast majority of learners on apprenticeship programmes do not need to know about quadratic equations and have an intimate knowledge of the novels of John Steinbeck.

Instead, they need to be able to quickly calculate the value of a 20 per cent discount, to be able to contribute effectively to a team meeting and to deal sympathetically with a customer complaint.

Those are skills which it is almost impossible to develop within the strict confines of an academic qualification.

The government clearly hopes that a revised GCSE will become an aspirational target for young people, but aspirations have to be realistic and achievable as well as challenging and with nearly 50 per cent of learners currently failing to achieve an A to C grade in maths and English, there is a real danger that we will disenfranchise the very people whom we should be supporting and encouraging.

Having already closed off an academic career, we are now telling them that the vocational pathway is no longer an option either unless they can achieve a qualification which they probably consider irrelevant and unobtainable.

My other concern is that FS is being side-lined before any credible evidence has been obtained as to its impact.

Surely we need some thorough research and analysis before effectively ditching a qualification which employers and practitioners alike believe is genuinely raising standards and competency levels?

It was very pleasing to read that the government is listening to employer feedback and re-evaluating the proposed grading scheme for apprenticeships.

I would urge it to adopt a similarly flexible approach on FS and allow employers to set new standards which retain the option of FS or GCSEs.

By all means continue to develop the standards for FS and evaluate their effectiveness, but let’s not consign them to the Museum of Ancient Qualifications when employers, practitioners and experts across the sector are voicing their almost unanimous support.

Instead, let’s re-position FS as the “gold standard” for vocational training. That will surely give us a much better chance of tackling the current crisis and providing employers and learners alike with the skills they so desperately need.

Roger Francis, director, Creative Learning Partners