Averil Young reveals how she makes numbers meaningful to construction students – and is building up young women and people from minority groups who want to enter the trades

An estimated 60,000 more tradespeople need to qualify through our colleges and training centres to reach the government’s ambitious new homes target.

On the front line of building trades training is senior maths lecturer and trade union representative Averil Young, who is on a mission to show young people that careers in the building industry aren’t just for “naughty boys”.

From union battles to demonstrating maths in action on construction sites, she’s breaking down barriers one brick at a time at Eastern Education Group’s West Suffolk College built environment campus. Here, she outlines a typical Tuesday…

4.45am

I take my two labs, John and Nigel, for a long walk around the arable fields and lanes around my home near Bury St Edmunds. Seeing the sunrise and hearing the birds singing gives me the mental clarity I need to start my day. If I’ve got something on my mind, by the end of my walk it’s not a problem anymore!

After boiled eggs on toast, I drive to work. I’ve taught at West Suffolk College for about seven years since moving here from London to be with my partner, Malcolm. At first, I taught English, which is what I did my degree in. Then I got roped into teaching functional skills maths due to a shortage of maths teachers.

The college’s built environment campus feels like home to me because I was born into the construction industry. My father had his own concrete firm, so my earliest memories were spending weekends toddling around his yard in the Isle of Dogs.

8am

I’ve got emails to answer as part of my role as a University and College Union (UCU) rep. There are some tricky cases, but most questions put to me are around, ‘can an employee do this?’

I became a union rep after noticing a pay disparity in my department, which I felt strongly shouldn’t be allowed. If you’re doing the same job and have the same qualifications, you should be paid within the same clear banding. But at the time it partly depended on how you negotiated in your job interview.

Then the college announced that the pay rise that year was one per cent – crumbs off the top table. I hate injustice so I became a rep to make sure that we got a decent pay rise, and that pay banding became more transparent, which it has.

9.15am

Most days I only teach in the mornings and spend the rest of my time supporting other staff with their training and development, fulfilling my rep duties and lesson planning. But today is Tuesday, a full teaching day.

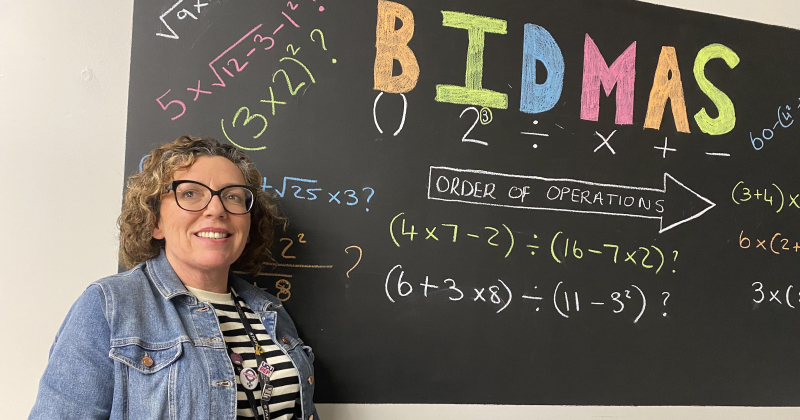

I’ve designed my curriculum around showing students why maths is relevant to them. There are maths workbooks specifically designed for construction students, but they’re very outdated so I use my own materials.

My students dislike maths and have a fear of it, often because they’ve failed it, so there has to be a reason for them to do it. I show them that there’s a lot of maths in construction and I teach them using a lot of the same equipment they’re using in their practical workshops.

I’ve got a painted door that we use to mark out shapes on, a brick arch former, and a caliper to map out my brick size and how many bricks we’d need. Using those tools helps bring maths to life for them.

10am

Today we’re out in our minibus visiting the new ambulance hub being built in Ipswich. Mark, our head of construction, is driving us there. He lets me try out all my crazy teaching ideas!

I try to take all our students onto a construction site at least once a year. It opens their eyes to what life is like in the industry and the professional expectations required of them, as well as demonstrating real-world maths.

We can only take 14 students at a time because we can’t fit more in the minibus, but all the students want to go; they absolutely love it. Sometimes we use the trips as an incentive for good behaviour.

Before we enter, we all put on the necessary PPE: safety boots, trousers, high vis and hard hats. Some sites also insist on gloves and eye protectors.

The sites themselves are busy and potentially dangerous, so we talk to the students about workplace behaviour and go for a health and safety briefing in the site office. That’s brilliant because it’s reinforcing what we’re telling students in our workshops.

Students often say they don’t need to know maths because they can use their calculators on their phones. But today, they can see for themselves how phones are not allowed on the large sites because they’re seen as a distraction.

One builder shows them how he’s using the 3-4-5 construction technique based on the Pythagorean theorem to get accurate right angles.

The workers also show them site plans which are scale drawings, to work out how long a particular wall has got to be. The students look at how many bricks are needed for each wall, and are shown how the timber is measured.

I ask the students to point out other examples they see of maths being used around the site.

Midday

Back on campus, I always ask students for feedback about what they’ve learned. I also arrange for industry professionals to visit and deliver workshops on the importance of maths, as well as the attitudes and behaviours expected on site.

They might still say they don’t enjoy maths, but they leave with a clearer understanding of why it matters – and they come to the next lesson more engaged.

Every construction company that has hosted us has been brilliant with the students, but the industry still needs to work more closely with FE.

When it comes to maths, I think there’s more colleges could do to work with other industries too – taking catering students to visit restaurant kitchens and talk about proportional ratios in recipes, for example.

1pm

I always bring my own lunch. Whenever I’m trying to be good, it’s a salad. But you know there’s a chocolate bar coming out later!

We’ve got a lovely staffroom where we sit together to eat, watch the news and have a good chat.

I’m guilty of sometimes catching up with work in my lunch break but I try not to. The more you do the extra work, the less likely the college is to employ more staff so it’s to your own detriment.

After lunch, I’m supporting a new teacher with behaviour management. Many people come into vocational teaching directly from industry, bringing with them fantastic knowledge and experience. But a classroom is a very different environment to a construction site, and new teachers often need support not just with managing behaviour, but also with developing effective teaching and learning strategies.

Helping them make that transition is key to building their confidence and ensuring they can engage and inspire their learners from day one.

2pm

For my next class, I’m teaching functional skills maths through the lens of financial literacy, so my students can learn how to budget for themselves. Teaching them about loans, credit cards and mortgages helps them to understand percentages.

They do a project to calculate how much they would need to save up to buy a house. We start talking about fluctuation in interest rates, and it turns out that a lot of them have never heard of interest.

They ask me, ‘why don’t they teach this in schools?’ I ask the same question. It’s super important that they understand these things, and it’s what they want to know.

Last week we discussed how much they would need to save up to learn to drive, buy a car and insure it, because they all want that. I went through the realities of how long it would take them to save – a long time!

Some of them said they would pay monthly, but they didn’t understand at first that a monthly payment is actually a loan.

4pm

Before I head home, I have emails to send to some local schools. I’m pushing for more diversity in the construction industry, which is still white male-dominated.

Only one per cent of the jobs on the traditional trade tools are done by females and 12 per cent in the industry overall. And things aren’t changing quickly enough; of our 70 student brickies, only two are girls.

So I’ve started going into schools to run workshops on construction, particularly aimed at females and culturally diverse groups, to show young people the variety of careers that are available. My college leaders can see the benefits in terms of helping with student numbers.

There’s a massive skill shortage in construction, so we need to change the narrative about the sector.

A lot of our students haven’t attended school for a few years by the time they come to us, sometimes because they were excluded. I think some schools are still giving career advice of ‘you’re naughty, you can be a brickie’.

It’s time to say auf wiedersehen to that image, and see construction for the respected profession that it is and the diverse career opportunities that it holds.

School pupils and their teachers are often interested when I tell them about the variety of sector jobs – like being a drone operator on sites. They’re also surprised that bricklayers can earn a very decent wage – more than us teachers!

The response I’ve received in schools has been great, so I want to push forward with that work.

4.30pm

I make some phone calls as part of the work that I do to support women in the construction industry. Helping women to improve their lives is something that I’ve always been passionate about.

In a previous role before moving to Suffolk I worked predominantly with women in the probation service in London. I learned a lot about women there – how we are repressed and how we suppress ourselves. I ran workshops on ‘Mr Right, Mr Wrong’ – red flags, as they call it now. Women sometimes can’t see a way out of something, but there always is a way.

Last year, I made it my mission to introduce my female construction students to positive role models in the industry. We managed to get tickets for the women in construction Anglia event and the girls loved it. It was really good for them to see other females doing what they do.

Last week we hosted our own women in construction event for the first time. When our female construction students started at college in September they were so quiet. Seeing them speaking at that event as confident young ladies was amazing.

5pm

I aim to finish at 5pm but, like everybody else, I might still be here at 6pm.

After enjoying a cottage pie for dinner, I end up watching the news. I promise myself I won’t because it depresses me too much but I can’t help myself!

I love my job because I’ve created roles within it that enable me to channel my energies into the things that I’m really passionate about – fighting injustice through my union work and promoting diversity through my school workshops and women in construction events.

No one asked me to do these things. I saw action was needed, and I’m fortunate to have been given the space in my work to champion what I believe in.