Successive governments are not giving up on the idea of getting former military personnel into classrooms, but could FE be a better fit than schools proved to be?

Facing a retention crisis and wringing their hands about behaviour standards, education secretaries still find the idea of a sergeant-major whipping students into shape just too tempting. Now the first cohort of ex-military staff on a programme called Further Forces – which we bet you have never heard of – will qualify this year.

Launched for the FE sector in 2017, the scheme “retrains and supports service leavers into teaching in subjects including science, engineering and technology” in the face of a “recognised shortage” of such staff, according to the Department for Education (DfE). Can this initiative succeed where others have failed?

There are promising signs, but the programme is under pressure. Funding is only guaranteed until March, at which point 210 former forces personnel should be on the programme.

FE and military have similar mentality: discipline and high expectations

Only 83 are so far signed up, meaning the organisers must more than double the figures achieved over the past two years in the next four months. It’s a horribly steep target for the Education and Training Foundation (ETF), which has been commissioned by the DfE to deliver the programme.

It also sounds worryingly familiar. Our sister paper FE Week has reported extensively on Troops to Teachers (also optimistically alliterative),which was introduced in 2012 and expected to recruit hundreds of veterans into classrooms. But the scheme, which had a £10.7 million budget, recruited only 106 qualified teachers over five years.

Troops to Teachers has now been abandoned, but education secretary Gavin Williamson, a former defence secretary, has still announced big training bursaries for ex-military personnel.

Yet schools are not the same as the further education sector – far from it – and it is worth noting that the ETF has managed to recruit about 80 people in two years, a far better rate than 100 in five.

There are two national hubs, one in the north of England managed by the Association of Colleges, and one in the south managed by the University of Portsmouth, with mentoring support from Brighton University.

In targeting ex-forces professionals to deliver vocational qualifications to young adults, the DfE, with funding partners the Ministry of Defence and Gatsby Foundation, might have hit on a formula that works.

Nigel Evans, principal of Weymouth College in Dorset, is clear that his recruit is “multi-talented” in a way that graduates straight out of university often are not. Since 2018 he has employed Nick Harper, a former lieutenant with the Royal Navy.

“We have massive difficulties in recruitment as a college on the coast because it’s rural,” Evans says. “Nick easily got the job.

This is a free qualification, a huge financial benefit for the college

“He’s the package – comfortable public speaker, confident. It wasn’t like taking on a general member of the public.”

Harper, who is studying for a level 5 certificate in education and training with Portsmouth University, was in the navy for 27 years, working as a ship’s diver, commando and parachutist. He now runs 12-week programmes with disaffected young people.

For Harper, the appeal of FE lies partly in the clear career structure. “People ask me, why didn’t you go into industry? But my medals always meant more to me than any financial bonus, and it’s the same in teaching.

“I want to get my certificates in education. I’d prefer to be achieving. Medals and qualifications make me feel good.

“There’s also a similar mentality in FE to the military. It’s discipline and high expectations.”

It would seem that the moral purpose and chain of command in colleges might be better suited to some former servicemen and women than a plush City office.

Harper comes with another unusual benefit. Ex-military staff can receive their full pension after 22 years, so many choose to leave at this point. As a result, they have an income that allows them to take the hit to their salaries when they move to teaching.

“My armed forces pension allows me to live the lifestyle I want in this job,” Harper says.

Jo Ronald, director of sport and A-levels at Hartpury College in Gloucestershire, makes another financial benefit clear. The teacher training costs of her employee, Hannah Payne, a former combat medical technician in the Army, are covered by the Gatsby Foundation.

“We would normally fund any brand-new teacher who isn’t qualified yet,” Ronald explains. “But this is a free qualification, so it’s a huge financial benefit for the college.”

At a time when FE colleges have suffered years of funding cutbacks, it is a significant subsidy.

Ronald also echoes Evans in praising the personal manner of her recruit. “Her background brings real resilience as a member of staff. Her discipline, organisation and resilience is first-class.”

But Ronald feels the programme has been seriously under-marketed. She had not heard of it until Payne approached them.

“I also haven’t been asked since if we could take any more recruits on,” Ronald says. “I’d love to.”

She is echoed by June Murray, principal at the Royal National Institute of the Blind College in Loughborough, who says that until her employee Andy Marsh, a former staff sergeant in the Royal Veterinary Corps, explained that he was on the Further Forces programme, she had not known about it.

“I had no idea. I’d like to say, we’re here, if you’ve got more people please let us know.”

She particularly values Marsh as a male role model for learners in a predominantly female specialist sector. “Males are so important and we barely get them applying. Lots of specialist colleges would be interested in this.”

Lots of specialist colleges would be interested in this

According to the ETC, there are 188 colleges “engaged” with the programme, which means they share their technical teaching vacancies. These colleges also receive fortnightly newsletters that include anonymised service leaver profiles, so they know who to invite to interview.

So who is to blame? Colleges which are not signing up and checking the newsletter – or the programme?

Cerian Ayres, head of technical education at the ETF, says “we need more vacancies from colleges”. Yet it would seem that many colleges, for whatever reason, do not know what they should be doing.

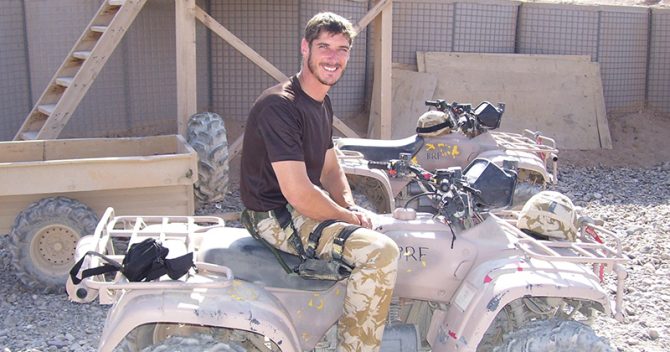

And the benefits they are missing out on are evidently huge. Ben Smith, who was in the Royal Engineers for 24 years, says his experiences in Iraq, Afghanistan and flood relief allow him to “bring alive” a career in the military. He is now a lecturer in uniformed public services, which includes the forces.

Meanwhile Karen Barnaby, formerly in the Royal Air Force police, says military staff are particularly suited to the diversity of students in FE. “Because I moved around so much with the RAF, I’ve got no prejudice,” she says.

“I’ve dealt with so many different people already – ex-offenders, people from different cultures in the Middle East. I’m really used to managing people.”

She is now a trainee lecturer in uniformed public services at Highbury College in Portsmouth and praises the high-quality mentoring. But she has one criticism – that she would have benefited from a longer lead-in time before teaching.

Recruits complete just six modules online before going into classrooms. “I’m from the military so I like to be properly prepared. I would say it needs an integrated start in the college of at least two weeks before you teach.”

Another point is that all recruits FE Week spoke to were lecturers either in sport or public services, with none in “technical” roles such as engineering or technology – the supposed focus of the programme. Are there enough technical experts leaving the military to fill gaps in FE?

But the impressive skills of these recruits are undoubted. Harper already has a level 7 certificate in strategic leadership and management from the Navy. I ask if he might become a principal? “Who knows? Perhaps,” he grins.

There appears to be a much more natural affinity between the forces and FE than with schools. The Further Forces programme is definitely on to something. Let’s make sure this programme does not go the way of Troops to Teachers.

Your thoughts