Spending on degree-level apprenticeships has hit the half-a-billion-pound mark in a single year for the first time, and now accounts for over a fifth of England’s annual apprenticeship budget.

Figures also suggest level 6 and 7 apprenticeships will take an even bigger slice of the levy pie this year, as costly courses for accountancy/taxation professionals, senior leaders and chartered managers continue to soar in popularity.

Experts warn that while degree-level apprenticeships have potential to boost social mobility, the rapid rise in their share of the market is squeezing out opportunities for younger workers and threatens the sustainability of the apprenticeship budget.

‘Precious funding wasted on senior staff executive training courses’

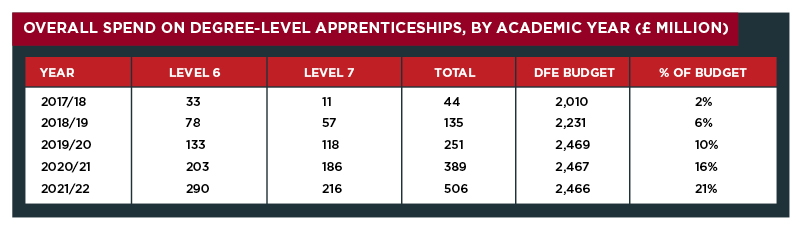

Since the levy was introduced, spending on level 6 and 7 apprenticeships has risen from £44 million in 2017/18 to £506 million in 2021/22 – hitting £1.325 billion in total over that period, according to new government figures released in a parliamentary written answer by skills minister Robert Halfon.

FE Week analysis of the data shows the degree-level programmes made up 21 per cent of the Department for Education’s apprenticeship budget in 2021/22, up from 16 per cent the year before.

There have been almost 180,000 starts on the courses – which are mostly taken by older workers – since their introduction in 2015. There were 10,870 in 2017/18 – 2.9 per cent of all starts that year – rising by almost 300 per cent to 43,230 in 2021/22, and hitting a high of 12.3 per cent of all starts.

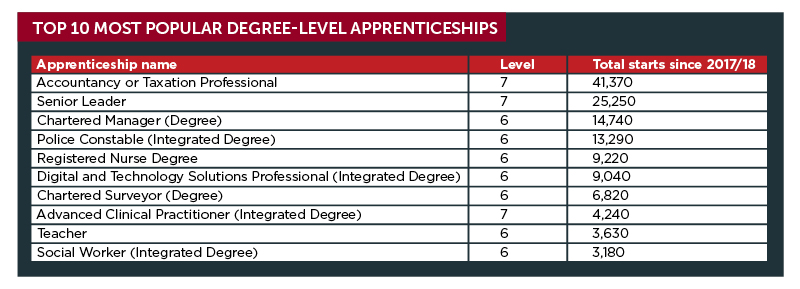

By far the most popular degree-level apprenticeship is the level 7 accountancy/taxation professional, which racked up 9,470 starts in 2021/22 and 41,370 in total since 2017. With an upper funding band of £21,000, this standard could use up to a whopping £870 million of the levy pot from the starts already recorded.

The second most popular degree-level apprenticeship is the level 7 senior leader standard, which has 25,200 starts in total since 2017/18. With an initial funding band of £18,000 before being cut to £14,000, it means that up to £420 million could be used to fund this training.

However, starts for this particular apprenticeship have started to plummet since the government removed its controversial MBA component from the scope of levy funding. Starts fell almost 40 per cent from 8,050 in 2020/21 to 4,880 in 2021/22. Business schools and universities can continue to offer the MBA as an optional extra, but the cost of it must be funded by their employer, an option that some have chosen to take up, as reported by FE Week three years ago.

Spending data for other apprenticeship levels have not been published by the government, but starts figures suggest less and less funding is being used to fund lower-level programmes mostly taken by young people.

For example, starts on level 2 apprenticeships dropped by 53 per cent from 374,400 in 2017/18 to 175,400 in 2021/22, while starts at level 3 fell by 11 per cent from 372,400 to 330,400 over the same period.

Tom Richmond, director of think tank EDSK, and a former advisor to government skills ministers, said: “When employers and training providers are allowed to completely ignore the interests of younger learners, it is unsurprising that new recruits are increasingly being excluded from our apprenticeship system irrespective of the long-term ‘scarring’ effects associated with youth unemployment.

“Precious apprenticeship funding continues to be wasted on sending senior staff on these executive training courses instead of supporting young people in the aftermath of the pandemic.”

Liberal Democrat education spokesperson Munira Wilson MP said the figures showed the government’s approach to skills is “broken”.

“Apprenticeships are a great way for young people to learn the skills our economy needs. But under the Conservatives, the number of apprenticeships for young people has fallen while more and more money is being spent subsidising higher-level qualifications. That’s not right,” Wilson told FE Week.

In response to critics, a DfE spokesperson claimed “it is wrong to suggest a rise in degree-level apprenticeships is taking opportunities from younger workers”.

They added: “70 per cent of people starting an apprenticeship do so at a lower-level and under-25s make up more than 50 per cent of all starts. We continue to encourage young people to consider degree apprenticeships, which blend the very best of academic education with hands-on, paid workplace experience.”

What the DfE chose not to point out is that starts for young people aged under 19 dropped 27 per cent between the levy’s introduction in 2017/18 to 2021/22, while starts for those aged 19 to 24 dropped 6 per cent, and starts over 25s increased 6 per cent over the same period.

Apprenticeship budget sustainability risk

Boosting the number of degree-level apprenticeships is one of skills minister Robert Halfon’s top priorities.

In his answer to the level 6 and 7 parliamentary question, which was tabled by shadow skills minister Toby Perkins, Halfon said that take up of the apprenticeships has grown again this year and represented 16.2 per cent of all starts (33,180) between August 2022 and January 2023.

Rising degree-level starts will heap pressure onto the DfE’s apprenticeship budget, which was 99.6 per cent spent in 2021/22.

The government’s apprenticeships quango and the National Audit Office previously warned that apprenticeships were costing around double what was expected, and that the system was heading for a potential “overspend in future”.

But pressure was eased when the pandemic hit.

The Treasury boosted the DfE’s apprenticeships budget from £2.466 billion in 2021/22 to £2.554 billion in 2022/23, and plans to increase it further to £2.7 billion by 2024/25. But experts have warned the government is now back on track towards an overspend, mainly because of the rise in degree-level apprenticeships.

Despite this, ministers have repeatedly played down apprenticeship overspend concern during interviews with FE Week over the past year.

Richmond said: “That the popularity of expensive higher-level courses is now likely to threaten the sustainability of the apprenticeships budget makes the exclusion of young people even more concerning.”

Social mobility challenges

Halfon’s parliamentary answer said degree-level apprenticeships are “important in supporting productivity, social mobility, and widening participation in higher education and employment”, pointing out that they are available for midwifes, doctors and construction quantity surveyors.

DfE data shows that degree-level apprenticeships for police constables, registered nurses and teachers have also proved popular.

But experts say the skills system has created imbalances leading to a “middle-class” grab on degree-level apprenticeships.

Emily Jones, deputy director at Learning and Work Institute, said: “Level 6 and 7 apprenticeships offer an alternative route to higher level training and have the potential to boost social mobility, but only if access to them is widened.

“Our research shows that the current system can reinforce inequalities, with employers tending to spend the apprenticeship levy on upskilling existing staff on higher level and more expensive apprenticeships, with younger people from disadvantaged backgrounds losing out. Higher level apprenticeships have great value but shouldn’t be at the expense of young people and programmes at level 2 and 3.”

Research from social mobility charity the Sutton Trust also previously found fewer degree apprentices were eligible for free school meals and from lower income areas than those on traditional university courses.

Carl Cullinane, director of research and policy at the Sutton Trust, said: “Given that young people overwhelmingly undertake lower-level apprenticeships it is a worry that they are being squeezed out. There is a balance to be struck in offering good quality opportunities at a variety of levels that will benefit both young people and employers.

“Apprenticeships should not be used as a band-aid for a decade of cuts to adult education, at the expense of opportunities for the next generation.”

If you think this is concerning, if you knew how many tens of millions of pounds are wasted in the NHS on “leadership academies,” high priced management consultants (think £1,000 per day and up) to coach managers for everything from how to give a speech to Meyers-Briggs personality testing.

The problem with the NHS is not that it’s underfunded. The problem is where the funds are siphoned off without any accountability.

Look specifically at Level 7 starts across all standards and under 19s…

The occupations that the brightest are being drawn to is insightful for many reasons.

Degree Apprenticeships are a conspiracy by Government, Big Business and Universities in favour of more money going to Universities.

Unis are particularly keen on courses that generate more than £9,250 a year – the max amount for an undergraduate degree and keen on courses lasting over 3 years.

They are a great way to cross subsidise.

The sector missing out is Further Education. They are getting less funding and HE is stealing their lunch on most of the “combined delivery models”.

The rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer.

Government likes it this way. Unllike undergraduates, there is no maintenance fee available and most students are local so Uni does not have to find more student accommodation. This keeps the capital cost of spending on buildings down and makes Unis and Govt happier.

Upper middle class teenagers are again the winners along with their parents (no parental contribution) big employers (who set off the educational costs against profits)