As the Manchester mayor’s flagship policy for students enters its second term, JL Dutaut asks if it’s one worth following – and if so, who should drive?

It’s boom time for Manchester’s colleges.

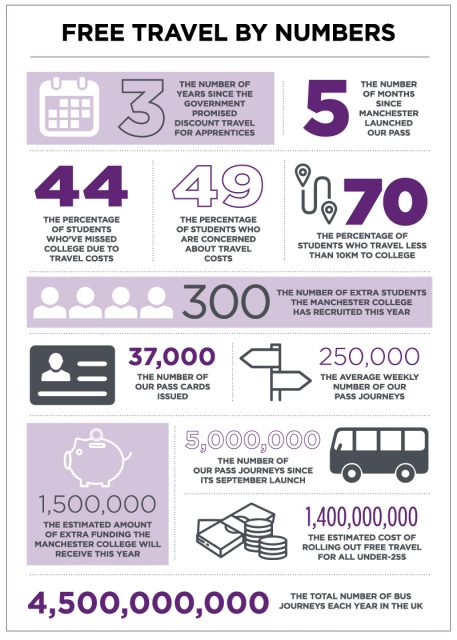

“We are seeing a significant increase in the number of students entering further education,” says The Manchester College principal and Greater Manchester College Group chair Lisa O’Loughlin. “Manchester College alone has seen more than 300 additional 16-to-18-year-olds enrol this September compared with last year, with many of the other colleges reporting similar increases.”

That represents an extra £1.5 million in extra per-pupil funding – a real boon whilst colleges await the 2019 general election’s promised increases in capital investment.

But to understand why Manchester is bucking the trend, we have to look to two other elections, both in 2017.

The first was the Greater Manchester mayoral election, won by Labour’s Andy Burnham. The second, the 2017 general election, narrowly won by Theresa May.

37,000 Our Pass cards have been issued, with cardholders making 5 million journeys

It was on the campaign trail that Burnham visited Bury college and heard from Olivia, a student working with charity Reclaim Project. “Do something to help young people with the cost of transport,” she told him, and it became part of his manifesto. By July 2019, mayor Burnham had announced the upcoming launch of a two-year pilot of Our Pass – giving 16-to-18-year-olds unlimited free bus travel and reduced off-peak tram fares in the whole Greater Manchester area.

The scheme, sponsored by a number of organisations, chief among them JD Sports, went live last September. Some 37,000 Our Pass cards have since been issued, with cardholders making 5 million journeys – around 250,000 a week – over the past five months.

The prompt and effective implementation of Our Pass is in stark contrast to the promise made in the Conservatives’ 2017 manifesto, in which the party committed to implementing “significantly discounted bus and train travel for apprentices”.

Subsidised travel is not a natural fit for Conservative economics. In fact, the Taxpayers’ Alliance suggests the effect could be to have taxpayers in rural areas (where public transport is less readily available) subsidising bus passengers in London, who account for half of the nation’s 4.5 billion annual bus journeys.

Nevertheless, a promised scheme has yet to materialise.

A promised scheme has yet to materialise.

The government maintains that it isn’t resting on its laurels. It has introduced the 16-17 Railcard (which offers a 50 per cent discount on train fares), while older apprentices can use the 26-30 railcard (which offers a third off all off-peak fares). It has updated guidance on local authorities’ duties “to support those in education and training post-16, including apprentices” with transport, and the DfE also points out that the ESFA provides additional payments to support “apprentices who are young or from disadvantaged backgrounds”.

In addition, the DfE says there are “a number of apprentice concessionary schemes offered by local authorities, individual train and bus operators and the National Union of Students via their Apprentice Extra card”.

But the Department for Education and Department for Transport are still working on the “joint proposal for discounted public transport for apprentices” – promised in 2017, and last discussed in parliament nearly six months ago.

The government says ‘get fired up’ but its policy is on the backburner

On that matter, the DfE passed on the opportunity to comment, stating that the joint proposal is being led by the DfT. When contacted, the DfT nearly missed its stop, and when comment did come, it was to inform us that “this policy is owned by the DfE”, leaving us to wonder just who is driving the bus.

Some information was forthcoming nonetheless, and it shows that while the government wants us to “get fired up” for National Apprenticeship Week this week, discounted travel for apprentices is very much on the backburner. It is not due to be delivered until 2021 – four years after it was promised.

Education and enrichment

The National Union of Students’ (NUS) vice president for further education, Juliana Mohamad Noor, is clear on her expectations. “We hope that in the coming budget we will finally see some money for this, otherwise it will be just another empty ploy to win over young people,” she says. NUS research shows that “49 per cent of FE students were concerned about the amount they spend on travel, and 44 per cent of those who had missed college had done so because they didn’t have the money to get there.”

In a system set up so that providers compete for students – and are held accountable for those students’ attendance – access and accessibility are paramount to ensuring equity for students and colleges alike. This is especially true for areas with higher levels of disadvantage, as well as for rural areas.

“Just another empty ploy to win over young people”

According to 2016 research by the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, 70 per cent of FE students travel less than 10km to their providers, and 50 per cent travel less than 6km. “Time and cost of travel are key constraints,” the report says, to “learners’ choices about FE.” The same report adds that “where travel is free, they are often willing to travel further”.

The report cites London as an example, but the evidence is also borne out in Manchester. At Trafford College, principal Lesley Davies reports that “learners say they now have the freedom to make an informed choice of where they wish to study without the restrictions they may have encountered before”. At open evenings, she adds, the college are seeing prospective learners “from areas of Greater Manchester that are further afield than would usually be the case”.

For Andy Burnham, education doesn’t just happen in the classroom. Our Pass, he says, “is designed to show everyone growing up in our city-region that we believe in them”. Referring to the substantial number of cultural offers bundled in with Our Pass, he adds that “The new opportunities we are releasing are giving young people the chance to explore the amazing place we live in and go even further.”

For Andy Burnham, education doesn’t just happen in the classroom. Our Pass, he says, “is designed to show everyone growing up in our city-region that we believe in them”. Referring to the substantial number of cultural offers bundled in with Our Pass, he adds that “The new opportunities we are releasing are giving young people the chance to explore the amazing place we live in and go even further.”

Access to enrichment opportunities is correlated to educational attainment, and it is also distributed unevenly between urban and rural areas and between more- and less-advantaged groups. In essence then, the free and discounted travel available to students in Manchester and London contributes to tackling within-city inequalities, but only further exacerbates the divide between metropolitan students and their rural peers.

While the government’s proposal to discount travel for apprentices can only be welcome, it will in fact do little to even that out, especially since applications for levels 2 and 3 apprenticeships continue to fall, so that an already-small target group is only shrinking further.

Travel poverty

Within Manchester, Our Pass isn’t without teething problems. Trafford College, for example, has struggled to communicate the policy to a small number of students, whose confusion about how their travel is subsidised has left them feeling that the college is doing less to assist them. In fact, they are simply drawing less on ESFA funding – and like all colleges in the Greater Manchester area, Trafford College even reimburses the Our Pass £10 admin fee for those in financial hardship.

But this does point to a confused state of affairs. With corporate sponsors, local government, colleges and bus companies themselves involved, who is taking ultimate responsibility for young people’s access to education, and who is accountable for its delivery now and into the future?

With T levels, the problem of inequality of access is only likely to get worse

By and large though, students at Trafford College have embraced Our Pass. “It takes the stress out of money and travel,” one said. Another volunteered that Our Pass “has made getting to work easier, and I don’t have to worry about getting to college”.

But individual stories are no evidence base, and while the six-term pilot is only in its second term, early indications from bigger data sets are also good. According to Andy Burnham’s social enterprise advisor and Our Pass lead, Rose Marley, a marked dip in bus journeys is evident over the half-term break, showing that a vast majority of those journeys are to and from schools and colleges.

The evidence is clear and growing that travel poverty is negatively affecting student choice, attainment and wellbeing. In turn, it is also affecting colleges and regions who can’t draw from the whole pool of local talent and are hobbled in delivering on their local industrial strategies.

But the reality is that regional implementation can only deliver unequally across the country. Left to local authorities, the effect can at best only be geographically uneven – and at worse it could compound wealth inequality. While the Manchester model is delivering for young people there, in economically left-behind communities where sponsorship could be harder to come by, taxpayers faced with footing more of the bill could decide not to pursue the policy.

What’s more, with mandatory placements of three months forming a major part of the upcoming T levels, the problem of inequality of access is only likely to get worse – and could mean the new ‘gold-standard’ qualification remains the preserve of so-called metropolitan elites.

Ultimately, delivering on the twin promises of student choice and of colleges as global Britain’s regional engines of growth will require more than piecemeal policy nudges. And even if nudges are all the policy we get, they will need to be delivered faster than this one.

But maybe policies in further education are like buses, and three might turn up soon.

This is an excellent article, in rural areas travel is a real challenge. In the South West, the cost of student travel is sometimes referred to as ‘tax on choice’. Free travel for 16-18 year olds could be a real driver for social mobility, help ‘level up’ opportunity and mean talent is not limited by postcode.

Couldn’t agree more with John. Fantastic initiative, great article and free travel is not only a game changer for colleges, but will save parents and students in challenging economic times hundreds of pounds a year.

Free travel, although a significant benefit to those in towns and cities, falls short for rural colleges and their students who suffer from generally poor access to public transport services. Providing access to this free of charge is only a partial solution. When the first service bus in to college leaves their village at 9:40am and the last service bus back leaves at 3:10 pm the free travel wouldn’t help too much, especially when the journey time is about an hour!

While in principle this is a positive scheme – its not so good for those colleges just over the GM border who now have to consider whether they need to further subsidise student transport costs from their limited budgets in order that they can ‘compete’ with Our Pass colleges and truly give people a free choice of where to continue their education post 16. The best we can do is try and offer a daily travel cost of £2 to all our students but this requires a upto a 50% subsidy from our funds – lets hope the success of the scheme may lead to a national or at least regional roll out