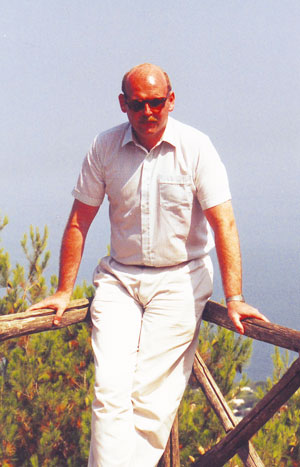

As a former Ofsted inspector, FE consultant Phil Hatton has probably seen some of the best and worst practices that teaching can offer.

He’s very keen to talk about his experiences — whether that’s the freedom of having left an organisation you’ve been part of for years, or the glee of being able to give others a glimpse of what goes on behind the curtain, it’s hard to tell.

“You get a feel for what a college is like very quickly,” he says.

“Sometimes you walk in somewhere and you just get this feel that there’s something very wrong.

“You can’t put a finger on it, but to give you an example, there’s one college I was at recently, and it had a brand new building. It was absolutely gorgeous.

“But the classrooms had glass windows into the corridors and as we walked along this whole corridor, I’d never seen so many bored faces on the students.”

Hatton’s exposure to poor teaching started long before his Ofsted days — his secondary school, Bishop Thomas Grant School in Dulwich was, he says, “probably the worst in the country” at the time.

“Of course you didn’t realise how bad it was then,” says Hatton, aged 59.

“When it came to GCSEs, they didn’t let you do more than five, and me and my friend did ten each — but that was only because our parents went to see the head and threatened to pay for the extra exams.”

Hatton and the friend in question then became the first students in the 16 years since the school had opened to go to university.

Hatton’s parents, Sean and Bridget, emigrated from Waterford, Ireland, in 1950 and both found work at the Victoria and Albert Museum, helping to set up exhibitions.

It was an incident while he was growing up on a council estate in leafy Dulwich that first sparked an interest in inequality, he tells me, when he and his brothers applied to join the local Scout group and were asked which school they went to.

“And when we told them, they said ‘Oh, are you’re Catholic? Well you can’t join, we’re Church of England [CofE] only’,” says the Bromley dad-of-two.

“And it must have been just this local Scout troupe, because the Scout movement generally is very anti that sort of thing.

“But all the other boys on the estate were in it and we weren’t allowed and it was the first time I ever realised there was a difference between being Catholic and CofE.”

His next brush with inequality changed the direction of his life dramatically, when he tried to get a place at university to become a vet, after visiting the family farm in Ireland.

“I applied to the Royal Veterinary College in London,” he says.

“And at interview they said ‘We’ve looked at your application, who in your family is a vet? You don’t mention your mother or father being a vet’.

“And I said ‘well they’re not’, and they said ‘what about your uncle? Aunt? No? Then why do you want to be a vet?’”

Without family connections to explain his interest, Hatton’s application was dismissed.

“In the end I went through clearing and managed to do a medical physiology degree but I was at the time pretty devastated,” he says.

At university Hatton found a novel way to earn extra cash — writing the poems in Hallmark greeting cards.

“I’ve seen some of them are still around — they were awful,” he says (but sadly tells me he can’t remember any of them off the top of his head).

Following his degree, inspired by his university lecturers, he decided to go into teaching and found a job at the London College of Fashion, teaching applied science in the form of trichology (the study and science of hair), where he was told he was also expected to teach hairdressing.

The experience would serve him well as an inspector, because he says, “it’s given me an insight into what makes good teaching”.

He became involved in supporting educationally disadvantaged learners, at the college, before moving on to become a senior science lecturer at North West Kent College — where he met his now-wife Carol — and then becoming deputy head of the department of food, hairdressing and community studies at Barking College.

It was during his time at Barking that he moved into part-time inspection for the newly-created Further Education Funding Council (FEFC), which he says, was prompted by “seeing how variable different colleges were”.

“And I think my own experience of having a really rubbish schooling without realising and thinking I could have done a hell of a lot better if I’d had decent teachers was slightly behind it,” he says.

“I was also intrigued as a staff development thing — if I could get into other colleges and see what they did I might learn what we should be doing.”

Anyone who’s worked with the ALI would say it was easily the best inspectorate

In 1998, Hatton became a full time inspector with the Training Standard Council and in 2001 moved with the changing inspection regime into the Adult Learning Inspectorate (ALI), an organisation he clearly has a lingering affection for.

“Anyone who’s worked with the ALI would say it was easily the best inspectorate,” he says.

“David Sherlock, who set it up, would say ‘if you’re inspecting it for us, tell the people how to put it right’ — so he had a very different attitude to Ofsted.

“They had a very negative attitude about people feeding back how to put things right — that’s changed with the requires improvement grading and putting inspectors in afterwards to make sure it changes, but that’s taken a very, very long time.”

The ALI was absorbed into Ofsted in 2007, with many of the inspectors making the

jump too, a move Hatton says was not popular with everyone.

“When I went along to the first meeting the inspectors were saying how disappointed they were that us ALI types had been allowed in because they didn’t think we were very bright,” he says.

“I pointed out that running or working in a college with tens of thousands of learners was very different to being head of a primary school with a few hundred pupils.”

And it’s these differences which seem to give Hatton pause for thought over the new unified common inspection framework.

“There’ve been six different inspection frameworks I’ve worked to over the years and every single one of them has got 80 to 90 per cent the same — it’s not that big a change,” he says.

“But I don’t honestly see why you have to have some of the behavioural type stuff which is very school specific — it’s important in schools because you do get schools with a reputation for bad behaviour, but it’s inappropriate for the FE sector, where we’ve got all the different ages.”

He adds: “But it helps keep one inspectorate, and I can’t help feeling that’s behind it — I was asked by a couple of Labour figures if I thought Ofsted was too big, so I think things might have been different if Labour had won the election.”

In 2013, Hatton left life as an inspector behind, and started his Learning Improvement Service consultancy.

“My work now is a lot more rewarding in that people can be totally and utterly honest with me because it’s confidential and so rather than coming across something in inspection, you can find what’s wrong and then hopefully you’ve got a year to sort it out.

“Some things are so easy to get right — if you’re teaching there might be three things you’re doing that could be corrected the next lesson, but that will have a big impact.

“You don’t do that for Ofsted, you might spot some good practice and look at that but you don’t look at little things people could put right very easily.”

————————————————————————————————————————————–

It’s a personal thing

What’s your favourite book?

Ulysses by James Joyce, which to me is one of the greatest novels of the 20th Century. It captures Dublin in the early 1900s. Reading it for the first time when I was 16 opened up a different style of writing and imagination to me

What do you do to switch off from work?

I travel to completely switch off, leaving the internet alone so that I can’t be distracted. Some of my best moments have been seeing whales and swimming with dolphins. I am a season ticket holder at Crystal Palace and attend every home match along with my best friend from school days. To chill for a weekend evening I love eating a well-cooked meal, followed by the theatre or a concert in London

What’s your pet hate?

There’s a few. Inequality including the aspects in FE that have been missed by the current inspection regime, such as too few women in engineering or men in childcare, low expectations and people who interfere with things that are working (particularly politicians who want to make their mark rather than to change things for the benefit of young people)

If you could invite anyone, living or dead, to a dinner party, who would it be?

I would like Michael Collins, one of the architects of the Irish Republic and a larger than life character, John F Kennedy and Nelson Mandela, because he showed such forgiveness against those who made his life absolute hell. I would want to know if they would have led different lives if they could have given advice to their 11-year-old selves.

What did you want to be when you were growing up?

I wanted to be a vet, working with large animals in a rural setting

Your thoughts