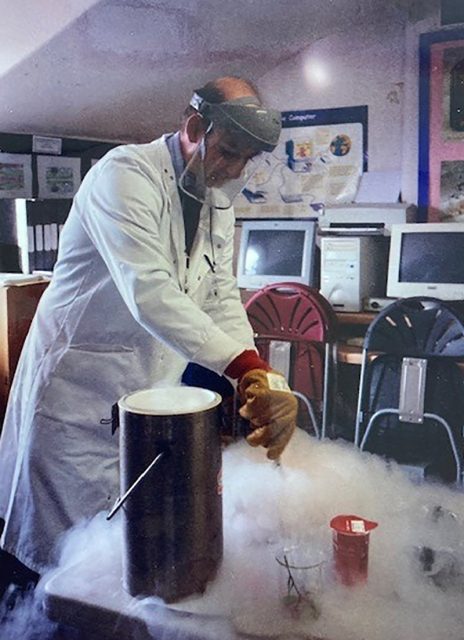

David Phoenix, a scientist who heads a group bringing together FE, HE and academies, shows why experimenting with a new model is critical for technical education

Quite how long education secretaries in England have been banging on about “breaking down” the divisions between technical and academic education and their respective sectors is anyone’s guess.

At a speech in 1987, then-prime minister Margaret Thatcher bemoaned the “great difficulty” she had getting a new technical and vocational initiative “into a number of schools because the education system itself was not prepared to take it”.

Some 33 years on, and Boris Johnson has joined in as he says “now is the time to end the bogus distinction between FE and HE”. It’s almost a rite of passage for the education secretary to trot out such a speech at some point. College leaders can be forgiven for having especially well-exercised eye-roll muscles.

Perhaps it would always take a scientist, rather than a polemicist, to gather evidence on the problem, test a theory and, once proven, apply it properly. Professor David Phoenix, chief executive of the London South Bank University Group, is chancellor of the university and boss of its subsidiary education groups, South Bank Colleges (which oversees Lambeth College) and South Bank Academies, which has an engineering-focused academy and UTC. The idea is for seamless learning pathways between the academies, colleges and higher education. It’s the only group in the country encompassing three education sectors under one governance structure, and needed special sign-off from ministers.

But Phoenix, the son of a joiner, didn’t set out to go into educational reform. He just liked science club.

“One of my big influences was my chemistry teacher, because he not only had a passion for the subject, but he supported us to do our own experimentation.” At this time Phoenix was in sixth form, having moved as a child from inner-city Manchester to Bolton. His first school had left him with big gaps in reading, maths and drawing that took a long time to fill in, he explains. Only by A-level had he caught up. “My teacher allowed us to have our little science club in the lab at lunchtime, to try things out. We created models of structures and quite complex purifications, and I found that really exciting.”

Having the freedom to try his own thing from scratch is something that Phoenix has valued – and made room for – throughout his life, sometimes to a quite extraordinary degree. First, he headed off to Liverpool University to study biochemistry and could be found in the labs once again, tinkering around. “I was lucky because there were lecturers there who let you go in and experiment, just try things out.” He recalls trying to find a solution to the fact most people hadn’t finished all their practical work. “We thought if we could just scale up our experiments, I could share some of my sample, and they could share some of theirs.” It didn’t go entirely to plan. “You find out with some of the more reactive elements, it’s not a good idea to scale them up! We certainly had a number of pieces of equipment that didn’t survive.” Behind what can seem a serious face at first, Phoenix’s eyes are definitely twinkling.

Exploding test tubes aside, by final year Phoenix was working on drug design. He went on to do a PhD “about a molecule called a penicillin-binding protein” – we’ll leave that there – and afterwards was awarded a grant to work at a top lab at Utrecht University, in the Netherlands. He was just 24. All this was cross-disciplinary work, he tells me. “I kind of worked at the interface of multiple sciences. I applied chemistry and biology, physics and biophysics.” Just so his calculations could keep up, he also did a part-time maths degree at the Open University.

An opportunity soon arose to transfer to the prestigious Pasteur Institute in Paris, but it was time to return to his now-wife, Stephanie, says Phoenix. He got a lectureship at the University of Central Lancashire, “and to be honest, I didn’t think I’d be there that long”.

But again, it was the freedom to experiment that kept Phoenix in situ. “That institution was absolutely fantastic in terms of the environment it created. I was allowed to just run with ideas.” Almost as though explaining a simple wish to pop to the shops, Phoenix then says: “I had an idea to develop a Centre for Forensic Science. The idea was quite straightforward: bring together practitioners with scientists, so ex-police officers, crime scene specialists, biologists and chemists.” It sounds madly fun, especially the “automotive crime scene” garage. “We mocked up break-ins, accidents, and we had people go in and take DNA samples. They had to put knowledge into practice.”

We mocked up break-ins, accidents, and we had people go in and take DNA samples

As with his scientific research, Phoenix sought to pull together disciplines and professions, applying different kinds of knowledge so better ways of working might be discovered. As dean and later deputy vice chancellor at the University of Central Lancashire, he remodelled the school of biosciences and created a new school of pharmacy with industry links. The strap line for the latter? “Fit to practise.”

It was in 2013, a few years after being awarded an OBE for services to science and higher education, that Phoenix took the vice chancellor role at London South Bank University. It was “not seen as a happy institution”, he says. “It wasn’t performing very well, but the potential was fantastic.” A huge consultation including everyone from “professors and cleaners” was launched and performance indicators began improving. Yet a Daily Mail article soon arrived, reporting that Phoenix had been given a £350,000 interest-free loan by the university to buy a house near the campus, prompting former education minister Lord Adonis to fume: “He already gets a salary of £295,000 […] I think this sort of behaviour by universities is disgraceful.” Phoenix says a condition of his new role was to live near the university, which the loan partially helped with and it was paid back once he’d been able to secure a mortgage.

Further challenges were to follow. Having taken on the 11-19 University Academy of Engineering South Bank in 2014, and the South Bank Engineering UTC two years later, Phoenix saw the benefits of taking over the struggling Lambeth College nearby to push forward the group’s reputation as a hub for technical and vocational education. Annual budgets, staffing arrangements and the college’s “strategic direction” would all pass over to the university under the transfer. Needless to say, there was resistance. “You can’t take ownership of an existing college, people said,” Phoenix tells me. “So I needed to get the skills minister [Robert Halfon] to agree to a national pilot, and he agreed.”

Finding the people in charge who will allow Phoenix and his team to experiment is clearly the man’s special skill. The college transferred to South Bank Colleges in January 2019. This January, construction will also begin on a £100 million Vauxhall Technical College, the second college in the group, with a proposed opening date of 2022.

The big question now is, is the experiment working? In 2017, the university achieved a silver rating in the government’s Teaching Excellence Framework and was named university of the year for graduate employment for the second year running in 2018 by the Times/Sunday Times “Good University Guide” ̶ meaning it looks increasingly strong as the powerhouse within the group.

The picture elsewhere is mixed, with signs of green shoots. University Academy of Engineering South Bank was graded ‘good’ by Ofsted in 2017, while South Bank Engineering UTC got ‘requires improvement’ last year, although inspectors praised staff for creating a “unique and nurturing learning environment”.

Lambeth College was also graded ‘requires improvement’ just four months after transferring last year, but a monitoring inspection in March this year found the proportion of 16- to 19-year-olds achieving their qualifications had “markedly improved”, leaders were taking “decisive action” on poor subcontractors and had “rapidly” changed the way they improve teaching.

So Phoenix is adamant – education provisions should work together like this. “One of my issues with the Sainsbury review [on technical education, in 2016] is that it spoke about learners having ‘choice’. But the problem is, you don’t know what you don’t know. What we’re doing is providing taster sessions for the college, the academy, the UTC, for students across the group. A student might go through the academy, do a level 2 at college, do an apprenticeship, or go on to HE for a business degree.” Phoenix explains that the proportion of learners getting level 4s in this country will not improve unless the “supply chain” is linked up in this way: “This requires FE-HE partnerships, and I think there is a key role for UTCS.”

It’s a compelling vision, and typically Phoenix has yet again broken the box with a new initiative. When apprenticeships for 15 of his UTC students were cancelled this year, his team “created a year 14” so they could stay on for an extended diploma and a higher national certificate exam with the support of the university. “This gives them the chance to get a level 4 at no cost to them,” explains Phoenix. This kind of year 14 offer “could really differentiate UTCs from academies,” he adds.

Last but not least, Phoenix recommends spreading good practice around the entire system – and thinking beyond the usual horizons, he means overseas too. As an advisor on science to the University of Guyana, he tells me “there is so much the college sector can offer to other countries in need of vocational education”.

It doesn’t seem too excessive to say that skills minister Gillian Keegan would do well to pay attention to what Phoenix is up to in this corner of London. If his performance indicators – particularly at the UTC and college – keep moving upwards, he may well prove a model for breaking down tired distinctions. And ultimately, for allowing educators to keep on “trying out”.

Your thoughts