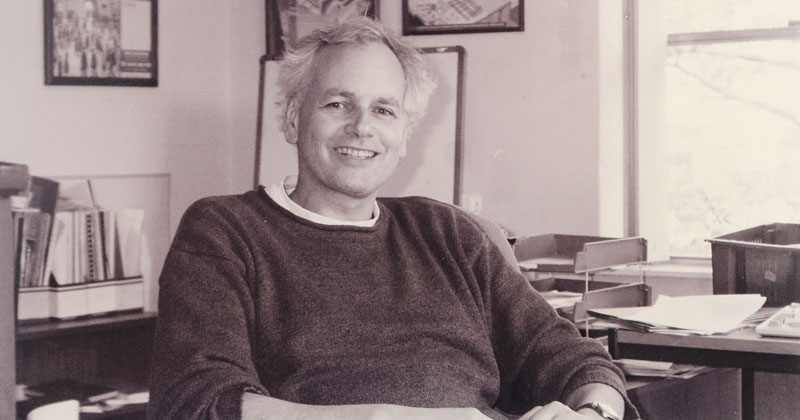

A lifelong left-winger who has dedicated his life to adult education, meeting Yasser Arafat and the Sandinistas on the way, Sir Alan Tuckett was knighted in the recent new year’s honours list. He spoke to FE on his work in a sector that’s badly understood by the politicians who pay for it.

Adult education guru Sir Alan Tuckett, who was knighted in this year’s honours, is best known for spearheading the growth of the National Institute of Adult Continuing Education – now Learning and Work Institute – spending 23 years at its helm.

What is less well known is that in pursuit of his cause, he worked with world leaders such as Yasser Arafat and Daniel Ortega, and even had the American beat poet Allen Ginsburg sleep in his bed (Sir Alan took the sofa…).

He’s been president of the International Council for Adult Education, advised UNESCO, founded charities, sat on a myriad of boards, authored hundreds of academic papers and held visiting professorships all over the world.

And if the characters that colour his stories reveal his political inclinations as being firmly on the left, his approach to politics is pragmatic. As chief executive of NIACE – a charity founded in 1921 – he positioned the organisation as “critical friends” of government: “We’d win contracts, but they recognised that we could, and would, be publicly critical on behalf of the interests of adult learners and the providers who provided for them.”

He has never shied away from public action. He made waves early in his career by organising a highly successful seven-day “teach-in” to protest adult education funding cuts in Brighton, capturing the media’s attention with celebrity visits and quirky classes, such as having a group of pensioners “painting the night away”. But he was heavily influenced during his eight years as principal of the Brighton Friends Centre, a Quaker adult education hub, by the group’s emphasis on dialogue and consensus-building for conflict resolution, principles he took with him throughout his career.

We’d always tell the government how we were going to fight them: privately, in advance

“We’d always tell the government how we were going to fight them: privately, in advance,” he says of his tenure at NIACE. “And if it was really inconvenient, like they’ve got some major policy coming out on Thursday, we were interested in the long run, not the immediate run. So we’d put it off for a week.”

Sir Alan sees community action as a “form of commitment to critical democracy”, and can find no reason to stop challenging a government that has showered him with accolades – first an OBE in 1995 and now a far higher honour. Quite the contrary: “Any recognition gives you the chance to make the case for saying ’it’s not good enough currently’.”

And that’s exactly what this doyen of adult education, who has spent his life making a fuss about the “invisibility” of the FE sector to politicians, is saying.

“I think we’ve had an almost entirely inappropriate industrial strategy in Britain,” he explains, adding that successive governments, inspired by the OECD’s love affair with the idea of “human capital”, have tried, wrong-headedly, to engage in a form of planning that links training directly to gaps in the labour market.

“From 2003 you get an increasingly narrow Gradgrind utilitarianism where there’s a crude link between what the government will pay for and what the outcomes are,” he says.

But this kind of top-down approach can lead to perverse consequences, he claims, drawing parallels between Train2Gain, “which included ludicrous things like paying Tesco for the induction training they were already doing so they would hit their targets”, with present-day criticisms about the levy apprenticeship system “validating things people can already do”.

And as white-collar jobs risk being wiped out “faster than blue-collar jobs went, with globalisation’s impact on manufacturing”, training must be “expansive” rather than “restrictive” and adults must be empowered to take control of their own learning.

“If you’re able to exercise your creativity you feel more agency, ownership and possibility – and you take that wherever else you go.”

Keeping learning is one of the ways of keeping out of being a burden on the state through the health service

He contrasts this with the government’s “incredible short-termism” and lambasts the former education minister Alan Johnson’s decision not to fund qualifications at the same level or lower than those already held: “People displaced by industrial change need more imaginative public policies than that.”

He is outraged that colleges have had their funding slashed in recent years while university budgets have boomed. But that’s not all; once upon a time, universities were funded to provide educational outreach in the community – a funding stream that ended in 1992. The Brighton Friends Centre was in fact an “extramural” post for the University of Sussex, from which Sir Alan was able to launch a pioneering adult literacy campaign at a time of general skepticism about the existence of adult illiteracy, creating resources that were initially reported to the local MP as “biased” for addressing themes such as squatting, but which were later lauded by government and distributed nationwide.

After Brighton, Sir Alan moved to London in 1981, as principal of Clapham-Battersea Adult Education Institute, where he stayed for seven years and, towards the end of his tenure, campaigned hard (this time, unsuccessfully) to save its parent organisation, the Inner London Education Authority.

ILEA would offer classes in “more or less anything you can think of” for “risible” fees (£1 a year for unlimited classes for pensioners) and had dramatically higher levels of participation than anywhere else in the country. Its dissolution in 1990 was a huge hit for adult education in the capital, and for society in general, he reckons.

“We’re an ageing society,” he points out. “Keeping learning is one of the ways of keeping out of being a burden on the state through the health service.”

Linked to the GLC, ILEA was likely closed, he jokes, in retaliation for its public support for the miners’ strikes. While working there, he was elected president of the International League for Social Commitment in Adult Education, leading to collaborations with the Palestine Liberation Organisation and its leader Arafat – who was “really committed to education” – in Tunisia and Gaza, as well as a visit to the Sandinistas in Nicaragua for one of their legendary adult literacy campaigns.

NIACE, which Sir Alan joined as chief executive in 1988, has an impressive history of its own, spawning respected cultural institutions such as the British Film Institute and the Arts Council. One of its lesser-known inventions was the army’s bureau of current affairs, organised by his predecessor W.E. Williams during WWII, where soldiers would have an hour of discussing contemporary issues “on the basis that if you’re fighting for democracy you ought to know what it’s all about”.

Adult Learners’ Week was really the first national festival focused on adults

As he tells this story, it’s clear why Sir Alan took the role at NIACE – it’s precisely this kind of creative approach to education that gets him excited, and to which he has dedicated his life.

Absolutely committed to “social justice and a world in which everybody can live with dignity and fulfil themselves”, and determined to get the media and policy makers to sit up and take notice, Sir

Alan threw his energies at NIACE into developing research capacity to demonstrate the “difference adult learning makes”. From 18 employees when he first arrived, he grew the Leicester-based organisation to 300 at its peak.

Adult Learners’ Week was Sir Alan’s major legacy project. Started in 1992 with the aim of showcasing adults learners’ stories, the concept was adopted by UNESCO and spread to 55 countries.

Now renamed the Festival of Learning and run by NIACE’s successor organisation, the Learning and Work Institute, he’s disappointed at the loss of a unique adult focus: “Learning means lots of different things; Adult Learners’ Week was really the first national festival focused on adults.”

The rebranding of NIACE is another move that has left him perplexed. He was five years gone from the top job there when it merged with the Centre for Economic and Social Inclusion to form LWI in 2016, but this didn’t stop him from arguing against the name change at the AGM.

“If I were running it, I would resuscitate Inclusion and NIACE as sub-brands,” he says. That way, “they’d be more visible, and the focus on adults wouldn’t be at risk”. But if throwing away “90 years of brand recognition” seems nonsensical to him, he’s keen to note his admiration for LWI’s work under the leadership of Stephen Evans.

On leaving NIACE in 2011, Sir Alan couldn’t resist another chance to work internationally and accepted the presidency of the International Council for Adult Education, leading to collaborations “with brilliant colleagues in India, Latin America and Iran” on the UN sustainable development goals. He’s still dodging retirement, with a job-share FE professorship at Wolverhampton University.

As I leave, I pass a replica medieval helmet on one of his living room chairs, which turns out not to be a costume left by a grandchild (he and his wife Toni Fazaeli – another FE veteran – have six between them), but rather a joke gift from his brother-in-law making light of his knighthood.

His own approach to his new title is similarly low-key.

“The recognition is for the sector,” he insists. “They don’t have the policies in place but I like to think it’s a tiny green shoot of change.”

It’s a personal thing

What are you most looking forward to when you retire?

I’m looking forward to more time on the allotment, where I’m incompetent – I like being the least competent person.

What’s your biggest regret?

That I never persuaded anyone to fund adult education properly!

Where would you escape to for a month?

Coogee in Sydney, Australia – I worked there once and would swim across the bay and back in the morning before starting my day.

Favourite thing about living in Leicester

Its cultural and human diversity, although once upon a time I would also have said the Leicester Tigers.

Who was the worst education secretary in your career?

John Patten: combining self-regard with inadequacy, he was even worse than Thatcher or Gove.

What did your parents do?

Dad was in the forces, so I grew up all over the place. Mum was a domestic servant before the war – so she used to tell me not to argue with anybody or I’d lose my job!

Your thoughts