Lee Elliot Major gave up a dream job to become the UK’s first professor of social mobility. Donna Ferguson finds out why he made the move to academia – and his latest plans to improve the life chances for our poorest pupils.

Lee Elliot Major recently confessed to a group of headteachers that he’d just walked past a London train station where he’d slept rough in his youth. “All the heads looked at me aghast,” the UK’s first professor of social mobility recalls. “They hadn’t expected that.”

A former chief executive of the Sutton Trust, he proudly lists on his CV the OBE he was given in 2019 for services to social mobility, with his many published works and a glittering array of academic honours, appointments and accolades.

But perhaps equally relevant to his job at the University of Exeter – although not listed on his CV – are his experiences as a comprehensive school drop-out in the 1980s, when he worked as a bin man and a petrol station assistant.

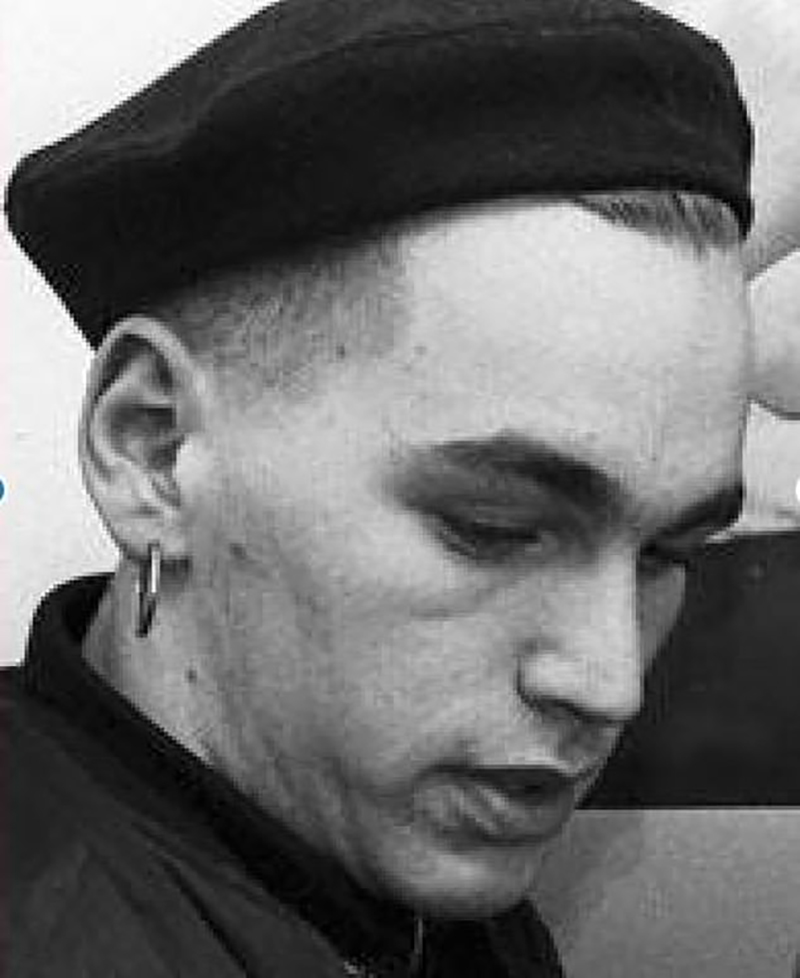

There were nights, back then, when he was “technically homeless”. He was a punk, he says, with “big earrings, eyeliner and blond spiky hair” and frequently clashed with his “quite strict” father. “My dad chucked me out a few times… I would have nowhere to go, and I remember…” he pauses, takes a deep breath … “him taking the front door key. That was quite a big thing for me. It did feel like I had… no home to speak of.”

He comes from a working-class family: his mother worked for the local council, his father was an electronic engineer. “No one in my family had been to university,” he says. “There are lots of people in sociology and economics and education, thinking about inequality and social mobility. To me, it definitely is a personal as well as professional passion.”

‘I’m an ‘awkward climber, detached from my roots, never quite at home’

He was always interested in social justice and education was always important. He was so bright that the toughest boys at his local comp “used to be quite proud of me – I remember one of them saying: ‘he’s going to be a brain surgeon when he grows up.’” Looking back, he thinks he may have been on the spectrum in some way…”I could sit around looking at mathematical equations for hours.”

His “very supportive” teachers recognised his potential and pushed him to apply to Cambridge. But instead of making him an offer, the Cambridge dons who interviewed him wrote to his school expressing concern for his wellbeing. “I must have spoken about my personal life… It was quite chaotic.”

Shortly after he stopped going to school, left home and managed to get his own place “on social security”.

He was working for a builder he had met in the petrol station when, with a friend’s support, he got a second shot at university. “My friend was from a typically middle-class family – dad was an architect, mum was a teacher – and they took me in for a time. That was really critical.”

His new “surrogate parents” encouraged him to retake his A-levels and he did well enough to secure a place at Sheffield, graduating with a PhD in theoretical physics six years later.

He is very aware that the “well trodden” university route he took often only enables social mobility for the most academic disadvantaged children, and agrees with Katharine Birbalsingh, head of Michaela School, that attending an elite university is not the only road to success for a young person from an impoverished background.

Future social mobility efforts should focus on making cultures inclusive to all talents, wherever they come from, rather than converting “working-class oiks into middle-class copies”, he says. “The big issue facing our society is shrinking opportunities to lead decent lives with affordable homes and good jobs.”

‘We have very few people in charge who understand FE’

Universities need to “up their game” in supporting students from poorer backgrounds – “not just getting them into university, but supporting them while they’re there”.

But he also thinks it’s outrageous that there is no pupil premium funding in FE to support the poorest pupils who do not go down the university route. “That would be my one funding ask, if I could get extra money,” he says, adding that one of the big problems facing the sector is the dominance of university-educated politicians and journalists. “We have very few people in charge who understand or empathise with FE colleges or vocational routes… we should focus on the young people who don’t go to university. But I also think there should be more university and FE links than there are at the moment.”

He is carrying out policy workshops with the Department of Education to address the “forgotten fifth” – the 20 per cent of young people who leave school without a grade 4 at GCSE in English language and maths. “Providing proper vocational options, as well as academic, is a huge black hole in our education system. And I think one of the reasons why we have so many young people leave without basic maths and English skills is because they are put off by a curriculum that is – and I know this sounds awful – a bit too academic.”

For many young people who are more vocational or creative, education in the UK is not as good as it could be.

GCSEs label some children as failures. “What I would have, alongside GCSEs and some vocational offerings, would be every pupil having to pass a National Certificate, which would be more functional skills. So, for example, how do you use maths in everyday life? How do you communicate?” It seems obvious to him that every pupil should leave school with those basic skills.

He left his “dream job” at the Sutton Trust for Exeter in 2019 because he wanted to have more of a direct impact on the practice of teachers and universities, and more influence on the government.

He is full of practical ideas about how social mobility could be improved.

For example, he would like Sure Start centres to be reintroduced “because otherwise, as our research shows, you’re always in catch-up mode in the school system, with huge gaps at age 5 and pupils falling behind”.

He also wants UCAS to reform personal statements, which he thinks offer middle-class children an unfair advantage, and to see more inclusive teaching. “Schools policy at the moment assumes that if you do good teaching – and that’s hard enough in itself – then everyone rises. I don’t agree.”

‘We should focus on the young people who don’t go to university’

Teachers, he says, should have a “really explicit focus” on disadvantaged learners. “That means knowing who they are and understanding their home environment, making sure you’re giving them feedback and thinking about what approaches benefit those children in particular.”

Like Birbalsingh, who announced last week that the The Social Mobility Commission will investigate which teaching styles work best to boost outcomes for poorer pupils, he thinks one of the most important questions the government needs to answer is: “What is it that schools, that are doing well for disadvantaged children, are doing? Which schools have done well over the past decade and how can we scale up that approach in an inclusive way?”

Persistent absence among disadvantaged pupils also needs to be addressed. “One of our studies showed that 40 per cent of children on free school meals are not coming to school regularly. They’re missing at least 10 per cent of sessions. This is a crisis.”

He sees it as a legacy of the pandemic, exacerbating educational inequalities that already existed. “Research has estimated that social mobility will decline for this generation… poorer children are up against it in a way that is so extreme now, compared to previous eras.”

Yet he admits he has paid for private tutors for his own children. “I don’t think you should castigate parents for trying to do what’s best for their children,” he says, adding that it was a joint decision with his partner. “I am obviously now very middle class… Sometimes I dwell on this a lot: to what extent am I challenging the system myself?”

After the interview, he emails to add: “My hope is that anyone from my sort of background has the chance to fulfil their potential whatever that may be. However, I would describe myself as an ‘awkward climber’ – detached from my roots and never quite at home where I’ve ended up. You carry your history with you – I guess I’ve learned to be more upfront about who I am as I’ve got older.”

Your thoughts