Agency gets tough with new rules on bosses

The Skills Funding Agency has beefed-up funding rules to stop rogue bosses setting up new providers to get their hands on public money.

The agency has carried out a host of changes to its eight-page Funding Higher-risk Providers and Subcontractors guidance.

It outlines the criteria that would stop a provider being considered for funding, either directly or through a subcontracting arrangement, and explains why bids might be rejected.

Among the key changes is that funding could be turned down if a senior member of staff is in place at a provider having been dismissed for gross misconduct from another provider.

The rule, which used to apply to just directors, is now in place for governors, senior employees or shareholders.

An agency spokesperson said: “The earlier version of the policy only mentioned a director and the change is intended to prevent these additional individuals from having any position of control or influence in an organisation seeking to be funded by the chief executive of Skills Funding.”

The agency can now also say no to bids if a provider has previously had their funding stopped early for any reason, failed to comply with a notice of funding withdrawal or failed to “remedy a serious breach of contract”.

It can even turn down bids where just a senior member of staff (or someone in a post already mentioned) was in place at a firm that had its funding stopped early — whatever the reason. The changes come just weeks after NTQUK bosses revealed how they were trying to breathe life back into their business after its agency contract was terminated early.

The move resulted in almost the entire 100-plus workforce losing their jobs, before the firm, which delivered apprenticeships in health and social care, customer service and business administration, went into administration.

But bosses at the 1,400-learner firm took the agency to an arbitration judge and successfully defended it against claims there had been “significant errors and missing data which constitute a serious breach of contract”.

Former NTQUK director Alex Mackenzie (pictured) said the new system was not “transparent”.

“Take the example of a training provider who has been through arbitration with the agency,” he said.

“If, for example, it is proven that the agency had acted unlawfully in terminating the providers contract, the agency could then restrict the trade of that provider — and its directors — without providing any transparent reason for doing so, other than the fact that it had previously terminated the contract.

“If a training provider considers, having won in arbitration, that it would like to re-establish itself, any future application for funding would certainly not be transparent. The application could be rejected automatically.”

The agency declined to comment on whether any specific instances had triggered the policy change. It also declined to comment on why the changes were needed.

Countdown to end of apprentice loans continues

No date has been given for the abolition of adult apprenticeship loans, despite Business Secretary Vince Cable’s (pictured left) announcement last month that the system was being dropped.

The Student Loans Company confirmed it was still processing applications for apprentice FE loans while it awaited government instructions to stop.

Dr Cable told FE Week three weeks ago he “accepted” the policy had failed and that it would be axed, although non-apprentice FE loans would remain.

Just 569 advanced learner loans have been taken out for apprenticeships in the nine months since they were introduced, compared to government forecasts that 25,000 would be taken out this academic year (by July 31, 2014).

Dr Cable said: “The advanced learning loans system has taken off for non-apprenticeships, but for apprenticeships we accept it has not succeeded and we’re dropping it.

“Regulations have to be put through Parliament to conclude it [apprenticeship loans system], but we’ve accepted it didn’t work and there’s no shame in that, but it will continue with the non-apprenticeship learners.”

An official announcement on the end of the apprenticeship FE loans system had been expected in the annual skills funding statement, which was postponed at the end of last year.

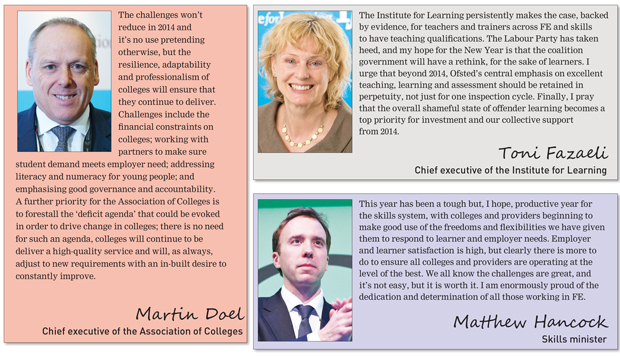

However, Skills Minister Matthew Hancock (pictured left) confirmed Mr Cable’s comments later the same day.

“While the newly available loans for FE have seen higher than expected demand, loans for apprenticeships have not,” said Mr Hancock.

“With the confirmation of a new funding system for apprenticeships in the Autumn Statement, now is the right time to reinstate co-funding for all apprenticeships ahead of more fundamental reforms, details of which will be publicised in the new year.”

The slow uptake has long-prompted concerns from the likes of the National Institute of Adult Continuing Education (Niace) whose chief executive, David Hughes, said the low figures confirmed that loans for apprenticeships were a “failed” policy.

He added: “We would like to congratulate the government for recognising this and accepting that they need to act, and to act swiftly.

“We are, of course, anxious to see the detail of the new proposals. Whatever is proposed, we are sure the government, employers, learning providers and learners and their representatives will need to work together to understand the full implications of this policy and how best to take it forward.”

Mr Hughes said adult apprenticeships were “essential” for both the economy and social mobility.

However, he said the axing of apprenticeship loans had left the group concerned about where future savings might come from, and about the possibility that loans might become the only funding mechanism for adults at intermediate and lower levels of learning.

“We hope that any consideration of introducing loans for other age groups and other levels of learning in the future will now be postponed,” he added.

Agency rule change allows grade three providers to keep taking on trainees

Providers that drop to a grade three Ofsted rating will be allowed to keep taking on new trainees under new government guidelines.

Providers that fell below a good (grade two) rating previously had to stop taking on new trainees, but they could let existing learners finish their programmes.

Now providers that were outstanding (grade one) or good when they started running traineeships, but are deemed by inspectors to be in need of improvement (grade three) within the 2013/14 academic year can carry on recruiting trainees.

It is thought the government relaxed the rules because of a disappointing uptake for its flagship youth unemployment policy launched last August for 16 to 23-year-olds.

A document explaining the revised rules, published jointly by the Skills Funding Agency (SFA) and Education Funding Agency (EFA), stated: “We do not see this approach as compromising the quality of the traineeship programme.

“We are minimising the risk to quality provision, but employing a pragmatic approach which will minimise the disruption of the delivery of traineeships.”

The report added providers with a grade three rating will now be expected to “improve rapidly” with help from an assigned Ofsted inspector, before they are re-inspected within 18 months.

Stewart Segal (pictured left), chief executive of the Association of Employment and Learning Providers, said: “This is a welcome and pragmatic amendment that will benefit young people and employers already engaged with traineeships.”

Julian Gravatt (pictured right), assistant chief executive at the Association of Colleges, said: “Traineeships are a new programme and the funding agencies are having to adjust the rules month by month as they see how they work in practice.

“We’ve always had some doubts about a rigid use of Ofsted grades to judge which organisations can and cannot offer traineeships, so we had no objections to this latest amendment.”

The document stressed providers must not increase the size of their traineeship programmes until they are re-inspected and achieve a grade one or two.

Providers that drop to a grade three in 2013/14 and are not re-inspected before the start of 2014/15 can continue to deliver in 2014/15.

However, they cannot deliver beyond those levels delivered in 2013/14 until they are re-inspected and achieve a grade one or two.

They will have to stop running traineeships if they fall short of a grade one or two in their first re-inspection.

Lynne Sedgmore, executive director of the 157 Group, said: “We are already concerned that important programmes such as traineeships are not available to all based on often out-of-date inspection results. These changes seem to muddy the waters still further.”

Despite there being no official figures yet, Ofsted FE and skills director Matthew Coffey told delegates at the Association of Colleges conference last November the traineeship uptake had been “disappointing”.

Kwik Fit said last month it had dropped plans to launch a traineeship programme after Ofsted inspectors gave it a grade three rating.

The firm came under fire when an FE Week investigation, which led to a BBC Newsnight probe, found it was looking to take on trainees, unpaid, for up to 936 hours across five months.

A Kwik Fit spokesperson said the firm had no plans to relaunch its traineeship programme in light of the rule changes for the “foreseeable future”.

FE Week most read news in 2013

FE Week is a printed newspaper and every edition (along with supplements) is sent to subscribers. If you do not already subscribe (tut tut) you can still benefit from £25 off an annual subscription in 2014. Find out more here (be quick!): http://feweek.co.uk/subscription/

Much of the newspaper content also goes online and in 2013 this website had more than a million page views.

To be exact, between 1 January and 26 December there were 1,147,180 page views and 545,934 visits by 249,770 unique visitors who viewed for an average of just over 2 minutes per visit (that’s more than 18,000 hours of viewing in 2014!).

Amongst more than 300 news articles in 2013, it’s always interesting to list the top ten based on page views.

.

The FE Week team also produced an incredible 16 supplements in 2013, a total of 256 pages of added value. Supplements were sent to subscribers and also made available for all to download.

Full supplement list for 2013 (with links) below.

| Supplement title . |

Sponsor | Month |

| Highlights from the AoC conference 2013 . |

NOCN | Nov |

| Skills Show 2013 souvenir edition . |

City & Guilds | Nov |

| Maths and English . |

Tribal | Nov |

| Apprenticeship tax credits . |

Pearson | Oct |

| Labour conference fringe event . |

Pearson | Sep |

| Technology in FE and Skills . |

Tribal | Sep |

| FE and Skills Inspections : 2012/13 review . |

n/a | Sep |

| Special report on traineeships . |

OCR | Jul |

| WorldSkills 2013 souvenir edition . |

NCFE | Jul |

| AELP National Conference 2013 . |

OCR | Jun |

| Adult Learners’ Week 2013 . |

apt awards | May |

| Guide to 24+ Advanced Learning Loans . |

Tribal | Apr |

| Celebrating 20 years of college independence . |

NOCN | Apr |

| Effective Leadership and Governance supplement . |

LSIS | Mar |

| National Apprenticeship Week 2013 . |

NCFE | Mar |

| AoC in India . |

NOCN | Jan |

Nothing like a damehood for Asha

West Nottinghamshire College principal Asha Khemka (pictured) tops the FE and skills sector’s representation on the New Year Honours list by becoming a dame.

She is in line for the honour for services to FE just five years after she was awarded an OBE for services to education.

Mrs Khemka, principal of West Nottinghamshire College since May 2006, will be the first Indian-born woman for 83 years to be awarded the DBE.

She said: “To receive such recognition is deeply humbling. This is a shared honour; shared with everyone who I have worked with over the years.

“West Nottinghamshire College and the communities of Mansfield and Ashfield embraced me.

“We have worked together to achieve an ambitious vision for our communities. Without their unwavering support this would not have been possible and I pay tribute to them.

“I am indebted to my husband [Shankar] and my three children [daughter Shalini and sons Sheel and Sneh]; throughout this journey, they have been my rock and my inspiration.

“My passion for FE is impossible to describe and grows more so every day. I am immensely proud to be part of this amazing sector.”

A Cabinet Office spokesperson said: “Under Asha Khemka’s leadership, West Nottinghamshire College has become one of the most eminent FE colleges in the UK.

“She has embraced the apprenticeship agenda, leading the college to become the largest 16 to 18 provider in the UK and finding jobs for 700 young people in the first year.

“Her charitable trust, The Inspire and Achieve Foundation, is especially focused on those not in education, employment or training. She is in the process of opening a skills centre in India.”

More than 20 honours recipients linked to the sector were announced, including nine OBEs and a British Empire Medal.

Among them was South Tyneside College principal Lindsey Whiterod (pictured right), whose OBE was also earned for services to FE.

She has worked in FE at senior management level since 2000 when she became director of the School of Business, Management and Computing at Newcastle College.

After three years she joined New College Durham as deputy principal, before returning to South Tyneside College as principal in October 2009.

Miss Whiterod said: “This is a tremendous honour, and indeed a great surprise. It is a very proud moment for me.

“I was taken aback when informed but I can see that I have been part of many good and positive advances and initiatives which I hope have benefited the students, lecturers and other staff that I have worked with.

“I have enjoyed a very happy and satisfying career and every stage has brought rewards as well as challenges, but I consider my best achievement to have been the driving up of standards at South Tyneside College as part of a wonderful team.”

Meanwhile, former West Cheshire College principal Sara Mogel (pictured left) was honoured with an OBE for services to vocational education.

She said: “This is a tremendous honour and I am delighted to see recognition for vocational education.

“When I started out to deliver vocational learning which aimed to make students employable and work ready this was an unusual thing.

“I was lucky to be surrounded by talented people at West Cheshire College who were able to bring about this revolution in learning and open it up to all.”

Dames Commander of the Order of the British Empire

For services to FE

Asha Khemka, OBE, principal, West Nottinghamshire College (Burton upon Trent, Staffordshire)

Order of the British Empire (OBE)

For services to FE

Cath Richardson (Wigton, Cumbria), former principal, Lakes College, West Cumbria

Brenda Mary Sheils (Stratford on Avon, Warwickshire), principal, Solihull College

Lindsey Janet Whiterod (Newcastle upon Tyne, Tyne and Wear), principal, South Tyneside College

For services to FE and voluntary services to the community in Bradford

Richard Edward John Wightman (Ilkley, West Yorkshire), chair of Bradford College Corporation

For services to FE for young adults with complex disabilities and severe learning difficulties

Kathryn Margaret Rudd (Cheltenham, Gloucestershire), principal, National Star Specialist College

For services to further and adult education

Elzbieta Wanda Piotrowska (London), principal, Morley College, London

For services to the community in South Yorkshire

Ann Cadman (Sheffield, South Yorkshire), director, The Source Skills Academy

For services to training and education of young people through Kirdale Industrial Training Services and to charity in West Yorkshire

Allan Oliver Jagger (Elland, West Yorkshire)

For services to vocational education

Sara Mogel (Flintshire), former principal, West Cheshire College

Members of the Order of the British Empire (MBE)

For services to adult education

Alexandra Graeme Day (Soberton, Hampshire), director, adult continuing education, Peter Symonds College, Winchester

For services to adult education and to the community in Greenwich

Ameen Hussain (London), manager, Asian Resource Centre, Greenwich

For services to education

Anne Laura Bryden (London), former language teacher, St Edwards Church of England School and Sixth Form College, Havering

Margaret Houghton (St Helens, Merseyside), head of French, Carmel Sixth Form College, St Helens

For services to FE

Sacha Corcoran (London), deputy director, City and Islington College

Anthony John William Douglas (London), music teacher, Morley College, London

For services to FE and the community in Northern Ireland

Joan Patricia Carberry (Belfast), family learning co-ordinator, Belfast Metropolitan College

For services to FE in Wales

Pauline Dale (Abergele, Conwy), programme area manager in hospitality, Coleg Llandrillo

For services to skills training in Scotland

Alan Douglas Boyle (Larbert, Stirling and Falkirk), chief executive, West Fife Enterprise Ltd

For services to skills training in the painting and decorating trade

Kevin McLoughlin (London), founder and managing director, K&M McLoughlin Decorating Ltd

British Empire Medal (BEM)

For services to local government and the voluntary sector in South London

Councillor Daphne Kathleen Marchant (London), director, Myrrh Education and Training

Chancellor Osborne buries hopes of college VAT refund

Hopes of a VAT refund for colleges look to have finally ended with Education Secretary Michael Gove admitting his hands were tied by the Treasury.

All 93 sixth form colleges in England, along with general further education colleges, pay VAT on goods and services, while schools and academies are reimbursed.

The Sixth Form Colleges Association (SFCA) has long campaigned for the “anomaly” to end, but Treasury Minister David Gawke said the policy would continue.

And Education Secretary Michael Gove said he was unable to secure funding from Chancellor George Osborne to address the issue.

James Kewin, SFCA deputy chief executive, said: “We are very disappointed that the government has decided not to address this longstanding anomaly, particularly when year on year funding cuts are pushing some sixth form colleges to breaking point.

“In that context, and when the government is meeting the VAT costs of new and untested 16 to 19 providers such as free schools and academies, this can only be described as a senseless decision.”

A cross-party group of 74 MPs had written to Mr Gove in October in a bid to change the situation, following a pledge from David Cameron, during Prime Minister’s questions on October 9, to “look carefully at the issue”.

The VAT issue is believed to cost sixth form colleges an estimated £30m per year and, according to research from the SFCA, has resulted in colleges being forced to drop courses such as modern foreign languages and further maths, as their funding reduces.

But Mr Gawke said in a Westminster Hall debate in parliament on December 17 that the Department for Education (DfE) had “considered whether adjustments could be made to funding for 16 to 19 education to recognise the differential VAT treatment of different types of providers”.

He said: “In particular, the DfE has considered whether it could additionally fund sixth form colleges by an amount equivalent to their typical VAT costs. The DfE has concluded that that is not affordable in the current fiscal climate.”

He added that while it would cost £20m to reimburse sixth form colleges, this would lead to the inclusion of general further education colleges as well, pushing the costs up significantly.

“Extending extra funding to FE colleges, which have a similar case to sixth form colleges, would cost some £150m,” said Mr Gawke.

However, Mr Gove acknowledged the case for change when he was questioned by the Education Select Committee the following day.

“There are some historical anomalies, not least the fact that sixth form colleges are treated differently in respect to VAT. I’d love to be able to [change] that, but money is tight,” he said.

“We looked at it before the autumn statement and the case is clear and strong.

“If I got more money from the Chancellor then I would like to and if we can be certain that it will be spent effectively, and there’s no doubt that sixth form colleges do, then I’d love to be to address that anomaly.”

When asked if he could put a timescale on potential change in the future, he said: “I’d like to but the Chancellor wouldn’t let me.”

Julian Gravatt, assistant chief executive of the Association of Colleges, said: “We are disappointed that government isn’t planning to act on the absurd anomaly which means that 16 to 19 free schools get VAT, but 16 to 19 colleges don’t.

“VAT law is fiendishly complicated with UK-wide and EU implications, so we’ll be pushing DfE to ensure that students are fairly funded wherever they study.”

The apprentice loans battle is won, but the campaign goes on

Business Secretary Vince Cable’s exclusive confirmation to FE Week that the apprenticeship loans system was being dropped was a victory for many in the sector, including the National Union of Students. But, as Toni Pearce explains, the fight against the wider FE loans system continues.

I’m incredibly pleased that Business Secretary Vince Cable confirmed the 24+ advanced learning loans system will be entirely scrapped for apprentices after it failed to attract anywhere near the number of people the government hoped.

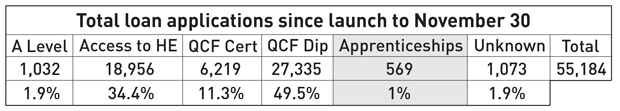

Latest figures, released yesterday, showed that of the 55,184 FE loan applications up to November 30, just 1 per cent were for apprenticeships.

The government U-turn is due, in part, to the incredible lobbying work that was undertaken by student unions across the country.

Since achieving significant concessions on the original proposals for FE Fees, our ‘No to FE fees’ campaign has particularly focused on the apprenticeships aspect, so it is incredible to see how our relentlessly focussed approach has chipped away so dramatically at a policy that government were absolutely set on.

The remaining system of FE fees is obviously still seriously unfair and problematic

The National Union of Students [NUS] has been committed to campaigning against the introduction of HE-styled loans for students in FE aged 24 and over studying at level three since their initial inception.

The scheme seems to have been a total failure and we have always said that this is a terrible policy which has created a system that doesn’t work.

It’s still astonishing that the government was hell-bent on implementing this policy even though its own research said that two thirds of learners wouldn’t take out a loan to study.

The policy risked putting people off studying and had grave impacts for those aged 24 and above who undertake a higher level apprenticeship taking out a loan of up to several thousand pounds so they could, essentially, pay to work.

The advanced learner loan is a major deterrent to study for those from lower income backgrounds. It means that the full cost of education was on the individual.

The remaining system of FE fees is obviously still seriously unfair and problematic.

FE is brilliant because it provides important second chances for millions of people. It is especially important for those who have families, bills to pay and already live within a tight budget.

The central issue still remains that we should be making FE as accessible as possible, rather than removing the public contribution towards teaching costs for so many adults who wish to re-skill.

Women will be disproportionately affected as they often return to study later in life after having a family. Those already economically disadvantaged such as black and minority ethnic and disabled students will be priced out of education.

Access for mature students to higher education will be threatened as they often acquire their highest pre-entry qualification later in life.

Research conducted by the NUS and Million+ suggests that nearly two thirds of mature students applying to a HE course with a level three qualification completed this qualification when they were aged 24 or over.

We simply cannot underestimate the hugely negative impact this policy will have on widening participation into higher education.

Now more than ever, we need to be investing in jobs and in a highly-skilled workforce. This is why we will continue to make the case for the system to be scrapped in its totality.

Toni Pearce, president, National Union of Students

Loans company awaiting orders to stop processing ‘dropped’ 24+ apprenticeship applications

The Student Loans Company is continuing to process FE loans for apprenticeships while it awaits government orders that the system has been “dropped”.

A loans company spokesperson said today, as new figures showed just 569 apprenticeship loan applications were made in nine months, the system was still operating despite Business Secretary Vince Cable exclusively telling FE Week it was being dropped.

He “accepted” the system had failed, but said non-apprentice FE loans would remain.

He said: “The advanced learning loans system has taken off for non-apprenticeships, but for apprenticeships we accept it has not succeeded and we’re dropping it.

“Regulations have to be put through Parliament to conclude it [apprenticeship loans system], but we’ve accepted it didn’t work and there’s no shame in that, but it will continue with the non-apprenticeship learners.”

It came the day before figures from the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills showed apprentice FE loans’ poor uptake had continued through November.

From the system’s launch up to the end of October, just 404 apprenticeship FE loans had been applied for — less than 1 per cent of the 52,468 total number of 24+ advanced learning loan applications, which includes A-levels and access to higher education, among others.

And that proportion showed little change taking into account November’s apprenticeship loan applications, which took the figure up to 569 (1 per cent).

It appeared well off target for the government forecasts of 25,000 applications for apprenticeship loans this academic year (by July 31, 2014).

An official announcement on the end of the apprenticeship FE loans system had been expected in the annual skills funding statement which has been delayed until, FE Week understands, the New Year.

Nevertheless, Skills Minister Matthew Hancock said: “While the newly available loans for FE have seen higher than expected demand, loans for apprenticeships have not seen high demand.

“With the confirmation of a new funding system for apprenticeships in the Autumn Statement, now is the right time to reinstate co-funding for all apprenticeships ahead of more fundamental reforms, details of which will be publicised in the new year.”

The slow uptake has long-prompted concerns from the likes of the National Institute of Adult Continuing Education (Niace) whose chief executive, David Hughes, said: “Today’s figures confirm our belief that loans for apprenticeships is a ‘failed’ policy.”

He added: “We would like to congratulate the government for recognising this and accepting that they need to act, and to act swiftly.

“We are, of course, anxious to see the detail of the new proposals. Whatever is proposed, we are sure that the government, employers, learning providers and learners and their representatives will need to work together to understand the full implications of this policy and how best to take it forward.

“Apprenticeships for adults are essential for a successful economy as well as for allowing better social mobility in our society.

“We are particularly keen on putting forward the learner-perspective as part of the new policy. This is particularly important in an employer-led system.

“I would like to see an Apprentices’ Charter which will provide apprentices with an understanding of what they should expect from their apprenticeship.

“This would help enshrine the commitment that apprentices will always be supported to learn for their career, not just for the job they are in today.

“The cessation of advanced learning loans for apprenticeships heightens our concerns about where future savings may come from.

“We are worried that the public funding cuts required over the next three to four years may result in loans being the only funding mechanism for adults at intermediate as well as lower levels of learning.

“We hope that any consideration of introducing loans for other age groups and other levels of learning in the future will now be postponed.”