Ministers are considering taking colleges back into government control, as revealed last week in these pages. But, Jess Staufenberg asks, was incorporation ever what it was cracked up to be?

There is a rising anxiety in the heart of government about the lack of intervention powers when colleges are failing. That’s what FE Week reported, in an explosive story, this month.

Perhaps ministers are muttering because, as the devastation of coronavirus comes swiftly on the heels of funding cuts, they’ve finally decided they can’t bear to watch any more colleges hit the financial buffers. Anyway, they’re looking to bring colleges under increased control, we heard.

More government involvement could mean further education colleges, which are officially categorised as in the “private” sector because of their borrowing and spending freedoms, are re-classified as in the “public sector”, like schools are.

The body responsible for this decision is the Office for National Statistics (ONS), which has criteria for whether an institution belongs in the public or private sector, and includes them in the national balance sheet accordingly. The ONS has announced no plans to re-assess the status of colleges – yet.

So in what way might the government “take ownership of colleges”, as FE Week reported? We spoke to three colleges leaders who remember the last time “ownership” was a clearly definable state: pre-1992, when colleges, their budgets, recruitment, courses and capital projects were all controlled by the local authority.

As of 1 April 1993, all further education and sixth form colleges – but not adult education service institutions – were incorporated, or removed from local authority control. Could the current government go the whole hog and return to that era? If so, what was it like and what could we learn from it? Ministers considering any changes would do well to listen closely.

I’m all in favour of local democracy, but they would tell you how to do things

“You often didn’t find out what your budget was going to be until halfway through the year,” sighs Adrian Perry, faintly amused, down the phone. Now a consultant, in 1988 he was principal of Shirecliffe College in Sheffield and from 1992 of Lambeth College in London.

“I’m all in favour of local democracy, but my criticism was they would tell you how to do things – what grade staff should be on and who to appoint and so on. It should have been the other way around. They should have told us what was needed and we would work out how to deliver it.”

Moving past strike action was tricky for college principals because the town hall was often in support. “The trade unions were very close to the local authorities. I had five strikes in one year.”

There were about 390 colleges back then, many led by men unimpressed with their lack of choice over which courses they could run, according to Dame Ruth Silver, now president of the Further Education Trust for Leadership. She was a clinical psychologist working for the civil service between 1982 and 1988, who joined Newham College as vice principal in 1986.

“That’s when I discovered, for the first time, people talking about getting the hell out of local authorities. I was taken aback by the hurry to get out.”

As a Scot, Silver was a believer in municipality and local democratic accountability – unlike many principals whom she attended meetings with. “They were vile complaining sessions in some cases.

“The complaint on the whole was about not being allowed to run the courses they wanted. The local authority wanted the colleges to do unemployment courses, for example.

“But lots of the college leaders didn’t want to do that – they wanted to be the old-fashioned technical colleges and have apprentices, who were better behaved. They had lots of difficult young people and they didn’t have the staff to deal with them.”

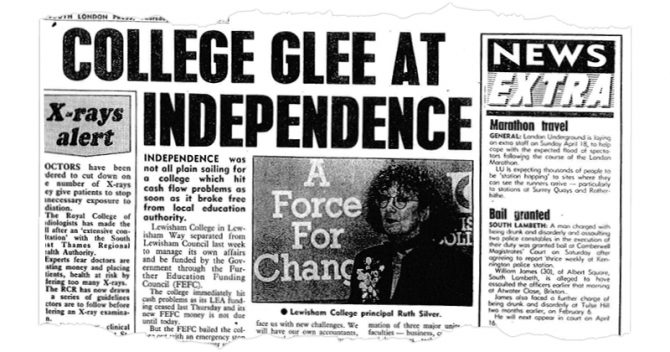

Yet Silver admits some shady political decisions were made in town halls. In 1991, the year before incorporation, she moved to Lewisham College.

“I remember the college had a leaking roof and the money went to the borough, who didn’t spend it on the roof. Instead they transferred it to Millwall Football Club! That happened a lot, political projects came first or schools came first.”

College leaders were “curtailed” by two main factors, explains Silver: elected politicians’ links to the trade unions, and that “school was compulsory and so elected officials paid more attention to schools because that’s where the votes were”.

But there was a serious upside to having a layer of government work closely with colleges – coherence of offer.

Before moving to Newham, Silver had worked at Southwark College under the Inner London Education Authority (ILEA), which was cross-borough and less tied to particular town halls.

This broader, regional level of government allowed for a post-16 sector whose institutions worked together, rather than in competition.

“ILEA was planned strategically. It was a lovely model, every borough had a college and people could go to any college in London. If you wanted to do art, you could go to the art college, or fashion there was the fashion college. ILEA would give you travel tickets to get to any college.”

The scramble to compete for other institutions’ students was not nearly as pronounced, and learners were supported to access a wide range of institutions.

They had lots of difficult young people and they didn’t have the staff to deal with them

Then a series of changes happened in quick succession. Margaret Thatcher’s government passed the Education Reform Act in 1988, ushering in “local management” of colleges and schools whereby local authorities were required to delegate certain decisions, such as staffing, to education leaders.

Soon after polytechnic colleges demanded the same independent, incorporated status as universities which John Major, who had taken over a year earlier, awarded them in 1991.

“The polytechnics disturbed the nest,” says Silver. “When college principals saw polytechnics had become universities and gained independence, lots of them wanted that too.”

It was something of a false analogy, explains Perry. “The polytechnics were national institutions, but colleges were local institutions, and that sometimes got forgotten. One of the drawbacks of incorporation was the withering of local collaboration.”

But the move brought a different kind of coherence: the creation of a national sector where spending rates in colleges began to vary less wildly between localities.

“Before incorporation, nationally there were enormous differences in the unit cost of efficiency,” continues Perry. “Some colleges cost almost twice as much per student as others. Incorporation brought a ‘levelling’ in spending. Convergence, it was called. The idea was to have a fierce incentive for growth while driving down costs. It also created a national sector: we were in the same circulars, in the same league tables, for the first time.”

The first of April 1993, when colleges became ‘non-profit institutions serving households’ (NPISH) belonging to the private sector, wasn’t exactly “VE Day”, laughs Perry, but there was considerable support among college leaders.

“It was quite something, the increased autonomy – commissioning building work was a very heady freedom.” He remembers attending a reception with Major who asked them, ‘isn’t it great to be free?’ Yet soon reality began to bite.

“Not long after we got a circular telling us how to behave. It was that Thatcherite thing: all God’s children have targets.”

Silver is more disparaging of the “freedom” she regards as mis-sold to the sector. “There is a lie in society that FE has had all the freedoms. We were still part of the public pension purse. We couldn’t run a surplus or borrow without government agreement. I once heard someone say, ‘we have as much freedom as a Marks and Spencer provider’ – every product has to cost the same and look the same. I think freedom is a myth.”

“It wasn’t as wonderful as was always made out,” concedes Perry.

“But efficiency and flexibility improved very sharply. The substantial increase in management autonomy was on the whole a good thing – it meant identifying problems, like why one course had lost half its students while another one had kept them all.”

The new regime also came with a range of new actors to enforce it. The Further Education Funding Council (FEFC), which would go through various iterations before becoming today’s ESFA, dished out funding and also launched a new inspectorate for further education, unlike the generalist HMI inspectors.

Making the same body responsible for funding and inspection sounds pretty dodgy, but having a dedicated inspectorate was a no-brainer. “This was a very purposeful inspectorate who could actually say what was good practice in construction!” says Perry. “Undoubtedly it had a sharp sting, but it was worth doing and people did prepare anxiously.” Completion rates of courses began to climb.

There is a lie that FE has had all the freedoms. I think freedom is a myth

But incorporation took many scalps, and the scars of repeated industrial action from frustrated, underpaid lecturers from that time arguably run deep in the sector to this day.

Susan Pember, now policy director at HOLEX, a professional body for adult education, joined Enfield council in 1986 and was responsible for administering four colleges before becoming principal at Canterbury college as incorporation arrived.

“It was exciting, really exciting. I loved running the college independently – I would have hated having shackles.”

But, as a former local authority official with budgeting and HR experience, Pember was in a “unique position” to take on the vast role of college principal, now labelled “chief executive”.

“For many principals who’d had people in the local authority doing all the finance, it was a huge shock. There was a big turnover of principals in the first five years, because the job was much bigger than they thought. We also had to make a lot of redundancies.”

She adds that during the period 1992 to 1998, the sector became “incredibly bureaucratic, some of it self-generated by principals who were very nervous and brought in lots of rules”. Teaching staff, as is often the case with change, bore the brunt.

Both Pember and Silver made the most of incorporation by appointing experienced people into HR and finance roles so they could get on with supporting lecturers and learners, and also maintaining local authority links rather than putting them out in the cold.

For instance, Pember appointed the chief executive of Canterbury city council to her governing body. But in the national picture many lecturers were unhappy.

The new Colleges Employers Forum had appointed controversial chief executive Roger Ward, a man who had already taken on the National Association of Teachers in Further and Higher Education over the polytechnic sector, a move which showed it would be taking a hard line with the unions.

In 1994 alone, 100 colleges went on strike over new contracts and the abandonment of the ‘silver book’ for pay and conditions.

Financial crises hit numerous colleges: in 1995, 1,500 full-time and 8,000 part-time posts were lost, and in 1996, 3,500 full-time posts were lost.

“Dash for cash” scandals hit throughout the 90s and by 1999, 20,000 full-time lecturers had been lost since incorporation. In their place, flexible contracts and efficiency drives had created a “gig economy”, says Perry, with “days on and off, rather than the old steady promotion up to a good salary”.

Debts were also piling up as colleges grappled with their new freedoms.

From 1997, generous funding under Labour made this less of a problem. But co-funding rules for borrowing in that period made later budget cuts more devastating, explains Pember.

“Before incorporation a college couldn’t borrow. Afterwards it was part of the criteria, and once Labour came in it was a co-funding model. For every pound you got in funding for capital, you had to borrow a pound, using your reserves or going to a bank. So if you were doing a £20 million project, you had to find £10 million yourself. That’s when debt really began to build up. As soon as austerity measures came in, you’ve got this huge debt and no means of paying it off.”

The latest figures from the Association of Colleges put collective college debt in 2016-17 at £1.25 billion. If colleges are brought into the public sector, it will be a lot to add to the government’s books. The bill from coronavirus is going to be so high that ministers perhaps care less than they used to.

Around the same time, more colleges moved away from local links, according to Pember. “About 10 years after incorporation, colleges stopped thinking local and started thinking regional or national. Many of them didn’t feel they needed any form of local accountability. The mantra gradually became that colleges are business, not community services.”

The ambiguous status was reflected at departmental level, where no one seemed quite certain how to categorise colleges. In 2007, they were in the Department for Innovation, University and Skills and by 2011 they were in the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. Yet despite being parked here, in 2010 the ONS reviewed the status of colleges and decided that the government actually had enough control to re-classify them as in public sector.

“No sooner had that happened than the coalition government moved colleges into the Department for Education and passed the 2011 Education Act which removed the need for colleges to seek government consent before borrowing and limiting intervention powers. The question persisted: who owned colleges? The ONS promptly moved colleges back into the private sector, but the answer still wasn’t quite clear.

The mantra gradually became that colleges are business, not community services

Indeed, the years that followed the 2011 Act read like a timeline of attempts to claw back an element of control.

The FE commissioner role arrived in 2013 to lead commissioner intervention where crises were already happening and also steer area reviews in a stalwart attempt to prevent them. The commissioner’s latest annual report shows 13 colleges were in intervention last year, higher than the year before.

“Administered college status” was introduced that meant “colleges will lose freedoms and flexibilities while they are turned around”.

In 2017, the number of colleges running out of cash prompted the Technical and Further Education Act, which extended commercial solvency laws to colleges and allowed the education secretary to appoint a special administrator to take over an insolvent college. Freedom was clearly a conditional scenario.

Yet, the fascinating fact is none of the three leaders FE Week spoke to would gladly give control back to local authorities.

“They cannot go back to how it was,” says Silver. “Pre-1992 doesn’t fit a modern world. There was a great deal to be critical about under local authorities – political wheeling and dealing.”

What has been lost, however, is proper local and regional collaboration. “The great thing back then was you sat around political tables as a sibling. That doesn’t happen any more – organisations won’t go to the wall for each other.” She suggests a collaborative “21st century version that’s designed regionally”.

The others come up with astonishingly similar solutions.

“My line would be some sort of regional education service for planning across an area,” says Perry.

Pember says a layer of local government needs to be regularly holding colleges to account for their area. “My view of the future is to cover the rest of the country with the equivalent of Mayoral Combined Authorities, so there is regional accountability to the mayor. It would be to bring in a much stronger scrutiny side. There should be an elected member who is asking that question: ‘what are you doing for this area?’”

The suggestions sound much like the ILEA structure Silver remembers as having been effective almost 30 years ago.

They want an extension of regional government checks and balances, but not of central or local government control – and certainly not full ownership.

In a way, ownership of the sector has been so slippery to define since 1993 that it’s difficult to say what conditions must be met to say the government does or does not own it.

The return of local authority control for spending and recruitment would certainly suffice, but that seems highly unlikely, particularly not under a Conservative government and when the sector’s leaders were largely opposed to that set-up when it was in place.

Yet, as Pember points out, the government has been increasing its powers over the sector in the last few years to the extent that she thinks ONS re-classification is inevitable. “They’ve ratcheted it up to the point where I think that colleges will fail ONS private sector classification”, she tells me.

The other possibility, of course, is that successive governments have always kept and extended enough powers over colleges that the “dream” of 1992 was never fully realised, and now it’s just a case of admitting publicly the government actually owns colleges. The charade of independence is more of a headache than it’s worth.

Either way, the tussle for ownership of FE continues. But a solution, taking inspiration from the regional pre-1992 structures, might be out there.

An interesting trawl back through all the names, acts and policies that one has forgotten over the years!

The idea of collaboration at local and regional level is as old as the hills now and reoccurs almost as often as debates about parity between academic ‘gold standard’ A levels and vocational qualifications.

I remember Ofsted starting off down the road of a regional approach to inspections for a while – remember the Isle of Wight and Nottingham – and lots of talk of including ‘cradle to grave’ institutions in those inspections. That didn’t last for long though…

Putting merits to one side, it is clear that Chairs and Governing bodies did not join and offer their services pro bono for an organisation structured for the public sector.

Such a change would provide an opportunity for Chairs to steer and governors to decide if they wish to continue on that basis. The alternative being resignations on a significant scale or payments on a level similar to an NHS Trust Board. ( NHS Trust Chairs earn between £18.6k and £23.6k,

with non-executive directors earning £6.2k.10 )

Might also cause a rethink either alternative?