FE Week meets a principal whose career has been defined by quiet consistency, and who has a few parting words for the sector’s leaders

It was a college principal who suggested I go and interview John Clarke, the retiring boss at Southport College in Merseyside and FE career veteran of 35 years. I’d asked for suggestions for interviewees, prompting the tongue-in-cheek response that Clarke was “worth celebrating” since he’d managed to “leave FE without a scandal – how many can say that?”, winky emoji face, etc. I was intrigued.

Speaking to Clarke, who confesses to keeping his “head below the parapet” during his career, it becomes clear why his record is both well-respected and super-clean – the man strikes you as especially modest. Despite years on leadership teams, there’s not a whiff of authoritarianism about him and, as it turns out, a dislike of overly hierarchical and rule-bound environments is a defining part of his personal character and professional motivation. In fact, an aversion to the same almost kept him out of FE altogether.

It was 1981 and Clarke was doing well. He’d just completed a PGCE specialising in adult literacy at the University of Leicester after three years as a community arts worker in Liverpool. But Clarke’s trainee experience in colleges, following the creative, grassroots engagement he was used to, left him cold. “I decided I’d never work in an FE college in my life. They were too stuffy, too bureaucratic. The staff room was dominated by filing cabinets and people didn’t seem to speak to each other. The culture put me off. I swore I wouldn’t.” He quickly follows this up by saying that perception was probably his own fault, being young and unused to paperwork. But on one point he remains firm. “It was massively overregulated.”

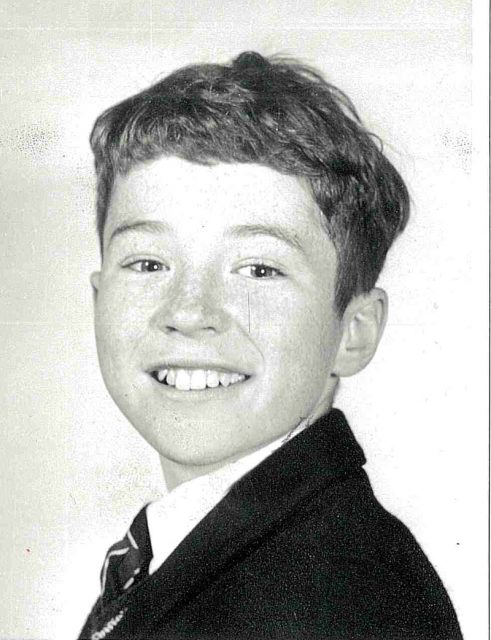

Clarke himself had had a fairly free existence, born in Ripon in Yorkshire to a father in the RAF, before settling with his parents and younger sister in north London. His father re-trained as a civil servant and his mother was a housewife. “I grew up in a settled, middle-class existence.” A clear memory sticks out from primary school. “One day we were escorted to the gym but I don’t think we were told what we were doing. We took a test and I think we might have been the last year that did the 11-plus.”

At first the young Clarke didn’t find friends at Watford Grammar School For Boys, which he describes as “setting itself up like a public school” with the teachers all in gowns. But by sixth form he was enjoying himself and won a place to read history at Churchill College, Cambridge – a college set up to take in state-educated children. “I was overawed that I was mixing with a lot of people from public school. What struck me was their confidence in themselves.”

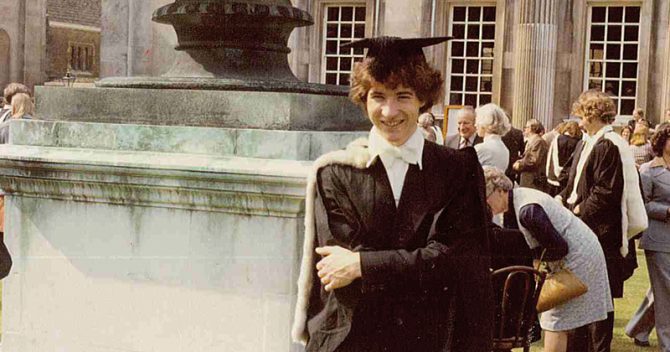

It was there that he heard about a scheme in Liverpool working with disadvantaged young people and adults. On his final day at Cambridge, Clarke didn’t look back.

“Community development was recognised as a profession. That has gone by the board now”

“It was almost literally the day after I graduated. I didn’t go home. I got on the coach up to Liverpool.” He had a job in arts engagement on the local authority’s “community council”, a long-gone late-70s Labour Party initiative. “It was when community development was still recognised as a profession. All that has gone by the board now.”

Clarke’s speech picks up speed as he describes with quiet passion the three years he says had a “massive influence on me, in terms of my thinking in further education”. Nearby Toxteth had one of the highest unemployment rates in the country and riots broke out shortly after Clarke left. “I’d studied history and sociology, and I arrived on this estate where virtually no one had gone to university. But I very quickly realised I was mixing with people as intelligent and able as the students I’d mixed with at university and from public schools. That sounds like a strange thing to realise, as obviously I understood the concept of disadvantage, but it was such a stark thing.”

Trying to provide better opportunities has driven Clarke ever since, using the style he learnt on the community council – “engage and involve people, allow them to shape some of what they’re doing”.

Still he stayed away from colleges, doing his PGCE but becoming an area youth worker in Oxford for four years, instead of becoming a lecturer. Eventually, he inched a bit closer to them. He took a job running a community education centre at Bolton College in Greater Manchester – almost, but not fully, inside the machinery of the FE sector. “It was a halfway house,” he laughs. “One of the big motivating factors for people, if you leave aside monetary rewards, is having control over what you do and freedom to take responsibility. Because I was working at the community end of things at Bolton, I did have some freedom, so that was good.”

Then incorporation of further education colleges arrived in 1993. Bolton College was removed from the local authority but councillors weren’t keen to lose the community education centre. “The council was very proud of it, and they decided they didn’t want it to go with the college. We thrived in the 90s.” Clarke led on European projects looking at adult education abroad and also helped set up a higher education access course at his centre. Bolton College, meanwhile, “hit the financial buffers”. By the end of the decade David Collins, who later became the FE commissioner and was then head of South Cheshire College, was brought in to save the situation. The first of two significant mergers in Clarke’s life was about to begin.

“He had a plan to bring the local sixth-form college and community education into the FE college.” The sixth-form college never joined, but Clarke soon found himself on the top team at the college as quality manager and then director of adult and community services. “I suppose it was the two or three hardest years of my life, because you were trying to turn around a college with big problems. But it worked.” It also brought to an end a division Clarke had always had concerns about – the separation of adult education from 16-19 further education. They belong together, he says.

It is perhaps ironic that the college in which Clarke found the greatest inspiration was run by a hierarchical and brilliant leader, John Smith at Burnley College in Lancashire. Here, as assistant principal under Smith, rules took on their proper meaning for Clarke. “I had huge respect for John. Personality-wise he was very resolute, he took no prisoners, and he was hugely driven. It was very hierarchical in lots of ways, it was very structured. But ultimately his view was, you have to give people the freedom to move on from the structures so they have the space to implement their own ideas. He had a saying: ‘You can manage people to be good, but they have to want to become excellent’.”

It was Smith who encouraged Clarke to apply for principal at Southport College. He has led it for almost nine years, and is currently handing the reins over to new college principal, Michelle Brabner. The college’s most recent Ofsted came out this Wednesday, with glowing references in particular to the merger Clarke spearheaded with the local sixth-form provision, the King George V College. The report reveals Clarke’s steady hand: “managers have introduced a more rigorous approach”, “senior leaders have made significant progress”, and more. But Clarke clearly sees the overall ‘good’ grade, which both establishments had already, as a modest achievement. Twice he mentions that he regrets not taking the college to ‘outstanding’ for the community, like his most admired mentor. He notes without a sense of martyrdom the huge effort required by a merger: “It might be the right thing to do morally, educationally and business-wise, but it probably distracted us for a year.”

“More than schools and universities, we are subject to a plethora of regulation”

For someone who has achieved so much, and worked so hard for others, Clarke is seriously unboastful about those facts. He says he has changed his view from that held in his youth, when he was “naïve to think I could make a difference to whole communities – I’ve scaled that down to making a difference to individuals.”

But he holds one conviction which has only deepened throughout his years in FE. “We’re still a massively overregulated sector.” The other day Clarke’s finance manager worked out that there are about 24 funding streams for colleges to struggle with. He presses his point home to me. “More than schools and universities, we are subject to a plethora of regulation. Someone, somewhere, has to simplify the regulation in FE.”

The sector has been lucky to have this even-tempered (and scandal-free) person. Let’s hope ministers listen to his parting words.

Your thoughts