In the first of a series of features exploring the themes raised by the College of the Future Commission, JL Dutaut looks at regionalisation, a Scottish government policy that transformed further education there, and is very much on the commission chair’s mind.

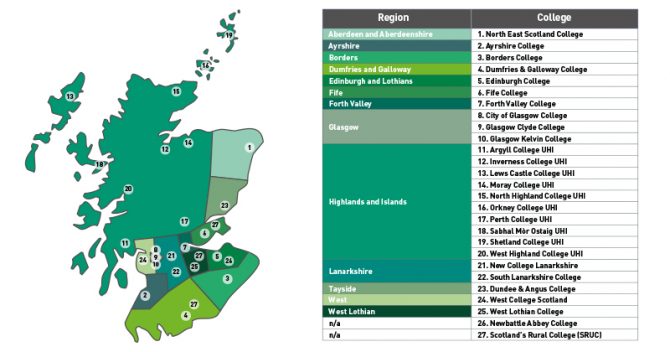

It is five years since Scotland’s policy of rationalising its further education sector came to an end. The three-year roll-out transformed Scotland’s FE landscape, merging 26 colleges along regional lines into ten so-called “super-colleges”.

In remarks at the College of the Future Commission’s first public event last week, chair and Scottish educational grandee Ian Diamond said regionalisation and the merger of the four Edinburgh colleges was a “good thing”.

From March last year to this August, Diamond was chair of the Edinburgh College board of management. He has since stepped down in order to become the UK’s chief statistician. His brief tenure at Edinburgh came six years after it was created from the conglomeration of Jewel & Esk, Stevenson and Telford Colleges, a process that saw the complete regionalisation of the city’s further education offer.

The Scottish experience

Edinburgh College was the last of ten super-colleges created as part of a dramatic realignment of FE provision across Scotland. As of 2018, it had approximately 19,000 students on roll across four campuses.

There is robust evidence on the benefits and drawbacks of the regionalisation agenda, but it includes no numbers for Edinburgh College. The Scottish Funding Council states that “although savings were realised through voluntary severance, the impact of the merger is difficult to separate from the ongoing financial challenges faced by the college post-merger”. Some of these issues, the report adds, are directly related to the merger.

In Edinburgh at least, regionalisation has not been straightforward. Notwithstanding, two years later, the SFC were able to show that the cost of delivery had been £71.6 million over four years. It calculated that annual recurrent savings for the nine new super-colleges for which data was available added up to £52.2 million, or some £210 million over the same period.

At the most basic level, Scotland’s education map has been re-drawn

The bulk of these savings have come from reductions in staff costs delivered through voluntary severance schemes. Others have been achieved through back-office efficiencies, increased purchasing power and estates costs.

The benefits of the policy included more effective leadership and governance, clarity of vision, strategy and objectives, and increased focus on learner needs. Across the merged colleges, a culture of flexibility was seen to be developing, and a major barrier to progress was (and in places remains) the creation and implementation of new working practices that take into account the multi-campus nature of such super-colleges.

Different models. Same challenges?

Of course, mergers and their consequences are not new in the English further education sector. Between 2015 and 2018, a period shaped by a DfE post-16 area review that encouraged colleges to countenance mergers, the Association of Colleges reports that 52 college-to-college mergers took place , peaking at 29 in 2017. Ten further such mergers have taken place this year, and more are planned for 2019-20.

In itself, this is simply an acceleration of a process that has been ongoing since 1993, and many of the mergers do represent regional rationalisations. City College Norwich merged with Paston College in 2017, and is currently consulting on a desired merger with Easton College. In FE Week’s last edition, principal Corrienne Peasgood made clear the process there was driven by the needs of the local community. Other mergers had in fact been declined on those grounds.

The slow growth of Cornwall College Group is another example. In 1993, St Austell College was formed from the merger of St Austell Sixth Form and Mid-Cornwall College. By 2015, Bicton College was the latest to join the group that arose from that initial merger. Such absorption of smaller providers accounts for 80 per cent of all mergers, suggesting a relatively predatory market, in which it doesn’t pay to be small. Regionalisation is nothing new to Cornwall, nor to many other regions.

By contrast, those who have created Newcastle College Group have little regard for localism and appear far more driven by the savings described in the SFC report. If regional rationalisation was ostensibly the original intent, its continued growth is testament to something else entirely. Today, NCG stretches from Carlisle to Southwark, via Kidderminster.

Stronger together?

This month, the DfE published its report The Impact of College Mergers in Further Education. Its headline finding was that, “on average, the effect of merging is statistically indistinguishable from zero”. That is to say, mergers led neither to improvement nor deterioration of college performance on average.

Averages easily disguise differences, and the researchers found that the differences in post-merger performance of colleges was large. Unfortunately, their analysis inexplicably lacked crucial information and as a result was not able to conclude which factors made mergers successful or not. Its conclusions are predictably asinine: the best that can be said so far from 26 years of mergers in England is that on average they have done no harm.

Meanwhile, like the DfE’s researchers, the Auditor General for Scotland has also bemoaned a clarity of baseline data against which to judge the regionalisation reforms. Nevertheless, the sector as a whole exceeds its targets for learning.

But regionalisation in Scotland was part of a broader package of reform that also saw further education colleges reclassified as public bodies, brought back national collective bargaining and brought in a new funding model. Regionalisation was not an end in itself, but a means to realising a political vision. It isn’t a silver bullet, and as far as evidence is concerned, it is at best neutral, and at worst entirely unknown.

What regions, exactly?

At the most basic level, Scotland’s educational map has been re-drawn, and that is the kind of policy Karen Spencer might appreciate. In response to Ian Diamond’s comments, the Harlow College and Stansted Airport College executive gave the chair a taste of the English way of things.

“I have a 900-year-old boundary, 900 metres from both of my colleges. I have four LEPs, two devolved authorities, one unitary authority, and we also work across Kent and Sussex. My nearest neighbouring college is in Tottenham, north London, not Essex. So when people talk about regionalisation, it’s complex.”

Regionalisation appeals to ideas of localism and community, bringing with it the benefits of a responsive and adaptable curriculum offer to suit the needs of learners and employers alike. But when courses disappear from the college up the road, lecturing jobs are lost and support staff contracts reformed, while executive pay rises and better resources are further away, regionalisation doesn’t carry the connotations Ian Diamond may have had in mind last week.

In Edinburgh at least, regionalisation has not been straightforward

This is the central tension of a policy that has already shaped the FE landscape in England for three decades with its ebbs and flows. Like Scotland, any future of colleges that entails a full and final reckoning with regionalisation will do well to do so as part of a broader and bolder reform agenda, whichever political and economic persuasion determines the vision.

Either way, the policy’s success will hinge on places like Harlow, and the legacy of borders, boundaries and botched policies that hamper its ability to collaborate meaningfully. Supra-regional entities like NCG will likely adapt, and redrawing the map might just be the rationalisation the sector really needs.

Your thoughts