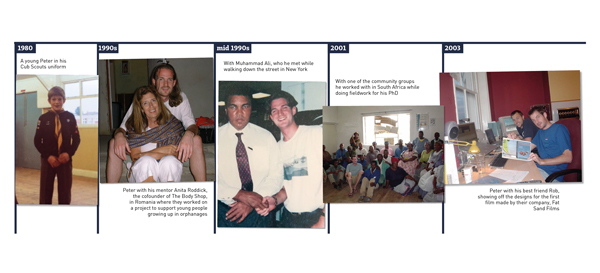

Struggling young people often need a mentor to inspire and guide them to better things — and Peter Kyle struck gold when Body Shop founder and tireless environmental and social issues campaigner Anita Roddick took him under her wing.

The Labour Hove MP, who is chair of the all-party parliamentary group for FE and lifelong learning, met the entrepreneur when he was 18 and working in the accounts department at the Body Shop’s headquarters.

The same undiagnosed dyslexia which was a major reason for why the now 45-year-old says he left school with “no usable qualifications” also led to difficulties in keeping up with the work at the retail giant.

It meant that he would work in his own time at weekends to keep on top of everything.

“Anita Roddick walked past one Sunday – I was the only other person in the office – and she came up to me and said, what are you doing here?” he says.

“She then took me up to her office and we were chatting about a trip to Brazil she’d just got back from and showed me her photographs. Then from there, I started to get these messages saying, Anita can’t do a talk at a school, she wants you to go in her place.”

Soon after that he made the move from office work to aid work, and “went to live in Romanian orphanages” on projects Roddick had founded.

“That’s what changed my life,” says Kyle, who still exudes commitment and charisma when he talks to me in his Westminster office.

He also credits his dad, Les, a former door-to-door salesman, as a key influence.

Kyle thinks that he inherited his work ethic and ability to be “single-minded in pursuit of what you set your heart on”.

Les and his wife Jo had moved down to the Sussex coast from Liverpool so that their children – Peter, who was born in Bognor Regis, and his older brother Chris – could “grow up in a very different place to his own upbringing” in “grinding poverty”, Kyle says.

Kyle marvels during our chat at the way his father managed to go to night school at the same time as working full-time during the day.

“He was working extraordinarily hard, but also understanding the value of education because he didn’t get it the first time,” Kyle says.

But despite his dad’s commitment to education, Kyle “hated every minute” of his time at Felpham Community College, the school he attended in Bognor Regis.

His dyslexia, which wasn’t diagnosed at the time, affected him so much that, he says, “for two or three times a week in the evening, I was kept after school to do remedial and handwriting classes, and sitting in a classroom with others who had either learning difficulties or other challenges”.

“I was thinking ‘I know I’m not doing well but I know that my issue is not the same’. And it was incredibly demotivating for me,” he says.

Not only that, he was gay at a time when the infamous Section 28 banned the promotion of homosexuality in schools by local authorities.

“Not knowing anyone else at all who was out, and being dyslexic – everything just mitigated against me,” he says.

After getting “terrible” O-levels, he says he “screwed up” his A-levels too.

His second chance at education came about thanks to Roddick, who suggested, after Kyle had spent a number of years working on aid projects in eastern Europe and the Balkans, that he should go to university.

It was at this time, at the age of 25, that he was formally tested for dyslexia. This revealed he had the comprehension and reading age of an eight-year-old.

“It was a revelation to know it – it made so much sense to me,” he says.

He applied to the University of Sussex, but was rejected due to his lack of qualifications, so took the rather unusual step of going back to his secondary school in order to have another go at his A-levels.

He admits that a 25-year-old in a school classroom full of 16- and 17-years-olds was “the weirdest thing” and his old teachers would come into the room “because they couldn’t believe it was happening”.

Despite getting the grades he needed the second time around, Kyle was rejected by the university again.

He says it took an intervention by Roddick – who has an honorary doctorate from the University of Sussex – before he was offered a place.

He ended up studying at the university from 1996 until 2003, gaining a degree and PhD.

“By any standards, it shouldn’t have happened,” he says.

“I’ve always found education a battle. Even when I’ve been in my comfort zone, like when studying development studies at university, I’ve always found the system of education at odds with me.”

Kyle’s own experiences led him to be an advocate for young people throughout much of his career.

Having completed his PhD, he set up a film production company with a friend, which he ran for 18 months.

That was followed by a stint in the Cabinet Office as a policy adviser, where he worked on issues including social inclusion and early years intervention during the final days of the Blair government.

The next step for Kyle was a move into the third sector, when he took over as the deputy chief executive of Association of Chief Executives of Voluntary Organisations (ACEVO) in 2007.

I am like a kid in a sweet shop

Kyle speaks passionately about what he describes as his biggest achievement from his six years there – setting up a commission on youth unemployment, chaired by David Miliband.

“We produced a piece of work that was absolutely outstanding,” he says.

Not only did the government adopt the key recommendations from its report, Kyle says, “the private sector got incredibly interested in it as well, because I believe the private sector is very interested in tackling the demand side of youth unemployment”.

That work led directly to Kyle being headhunted by Sir John Peace – then chair of three FTSE100 companies including Standard Chartered – to be chief executive of Working for Youth, a charity set up by some of the UK’s biggest businesses.

During his two years with the charity, he met with many “titans of the private sector” to discuss what they could do to address youth unemployment.

One result was a scheme Barclays set up, which he says resulted in 5,000 young people with no qualifications gaining an apprenticeship with the company.

“You pitch the idea and when they see the logic in it, big things happen rapidly,” he says.

In 2015, he stood for election as an MP in Hove and won – the culmination of a political ambition which had its roots in his time as an aid worker in the 1990s, where he experienced first-hand the impact of decisions made by governments, the UN and NATO.

Now that he’s in parliament he says he’s “like a kid in a sweet shop” because of the many opportunities “to get involved in something that impacts on young people’s education and the system of education”.

“If you read my maiden speech, it’s all about making sure we get it right for young people the first time, because most young people don’t get a second chance. If it was hard for me in 1989 to get the second chance I needed, it’s 10 times harder now,” he says.

It’s a personal thing

What do you do to switch off from work?

Gym, or a movie. I love going to the movies on my own. I need something to switch off – I don’t switch off unless something makes me switch off.

What did you want to be when you were growing up?

I never really knew. I remember going to my dad and saying, I want to be a policeman, and him saying something very sarcastic back at me.

Who do you turn to in times of crisis?

I’ve got a very long-suffering best mate! It depends entirely on the crisis. But I will always turn to other people. Usually it’s friends, but if it’s a big issue I’ll seek professional help. I lost someone that I loved very much, and I knew that that was an issue that you can’t get by with getting a bit of advice and a slap on the back from a friend. I think there are times when we all have to admit that our own innate life experiences will not see you through and you do need someone to guide you through it.

Who do you most admire, living or dead?

I would say Gordon Roddick, cofounder of the Body Shop. I think he’s always the unspoken one; he has no ego – which is unusual for someone of his achievements. He’s disciplined. He achieved a lot through discipline, and that means it’s something you can learn from. People like Anita were so genetically inspirational that I don’t know what I can learn from her, even though I spent so much time with her. But he is someone that I have learnt huge amounts from.

Curriculum vitae

Born:

1963 Born in Rustington, near Bognor Regis

Education & Career:

1975 – 1982 Pennyfields Junior School, Middleton-on-Sea, Bognor Regis

1982 – 1989 Felpham Community College, Bognor Regis

1989 – 1995 The Body Shop and Children on the Edge (funded by the Body Shop Foundation)

1995 – 1996 A-level resits, Felpham Community College

1996 – 2003 BA, Geography with Development Studies and Environmental Studies and PhD, Community Economic Development, University of Sussex

2003 – 2005 Running Fat Sands Films, film production company

2006 – 2007 Policy adviser, Cabinet Office

2007 – 2013 Deputy chief executive, ACEVO

2013 – 2015 Chief executive, Working for Youth

2015 – Present Labour MP for Hove, member of BIS select committee and chair of the APPG for FE

Your thoughts