You would be hard-pressed to find a better way of convincing teenagers to choose vocational learning over university than inviting OBE recipient Rod Bennion to tell them his life story.

The grammar school boy decided academia wasn’t for him after passing his A-levels and was instead taken on as an articled quantity surveyor trainee, the equivalent of a higher level apprenticeship of its day, with one of the UK’s largest construction firms, the Wates Group.

Bennion subsequently rose to the top of the corporate tree during 36 year at Wates, before retiring as group chief operating officer in 2003 to concentrate on helping disadvantaged young people train for the building industry through his role as chairman of trustees of the Construction Youth Trust.

The 68-year-old, who was given an OBE for services to construction training and the community in the south east of England in December, says: “I have never courted success and just try to get on with things.

“I was incredibly thrilled and proud to have been given the OBE, which I see as an award for all the good work done by everyone at the trust.”

Bennion, of Ashtead, Surrey, first became involved with what was then called the Construction Industry Trust for Youth as a trustee in 2000.

He said: “We had no staff at that time and raised around £100,000-a-year to help about 20 people into the industry through training bursaries.

“We decided to grow the trust in 2002 and I was invited to become chair.

“I applied to the Wates Foundation [the charity arm of Wates Group] for seed funding, which paid for us to employ our first director on about £40,000-a-year and it went from there.

“It meant that rather than just giving out bursaries, we were able to create construction projects, overseen by our staff and partner-employers, giving valuable work experience to disadvantaged young people.

“It could be something like finding out that a path needed building across a housing estate and arranging for 20 or 30 young people to help install it.

“By the time I stepped down as chair in May last year, the charity had an annual income of around £1.5m, around 30 employees, and supported up to 5,000 people-a-year.”

A lot of the young people who still turn to the charity, says Bennion, lack positive role models and may have struggled at school.

You will often find that young people in problem situations have parents who have never worked, so they had no example to follow

“You will often find that young people in problem situations have parents who have never worked, so they had no example to follow,” he says.

“I would find that if you wanted them to show up at work at 8am every day, you often had to ring them each morning at the start, as they wouldn’t know any better. But once given a chance, a lot of them really thrived and went on to things like apprenticeships.

“I am also proud of the work we did, during my time, with offenders, training and linking them with employers, so that they had a job when they came out and a chance of breaking the crime cycle. You would be surprised how many of them want to get out from under.”

Bennion was born in 1946 in Coventry, a city that still bore the scars of the Nazi bombing campaign on Britain’s industrial heartland.

He moved aged nine to Worcester Park, in Surrey, with his mother Enid, who died five years ago aged 87, father Arthur, who died 15 years ago aged 83, brother Douglas, now 60, and sister Elaine, now 72.

His father, a machine tool engineer, had secured a job with London-based Asquith Machine Tools, where he later became sales director.

“The first thing I had to lose [after moving south] was my Midlands accent because the other kids [in Surrey] were merciless,” says Bennion. “I learned to speak like a good Surrey boy quickly.

“I was always secure and happy though. The huge advantage that I had in life was that I came from a loving family home.”

Bennion attended Tiffins Grammar School, in Kingston, after passing his 11-plus.

“I think grammars gave a lot of people from ordinary backgrounds a better chance than they have now to get on,” he says.

“I had a brilliant, inspirational headmaster called Brigadier JJ Harper. His whole ethos, which has had a massive influence on me, was geared around developing the whole person not just their academic side.”

Bennion played in the school’s first-15 rugby team and captained his house side as a teenager and developed a passion for smart clothes and good music.

“I loved the Beatles, I still do, and was the perfect age [16] to appreciate them when they came out in 1963,” he says.

“All the old Victorian values were being challenged in the 1960s, which was so exciting. I tried to be a mod, like the proper East London boys, so used to dress smartly and drive around on a scooter.

“I was going to school one day, on the scooter, when my brake cable broke and I crashed into the back of my sport’s teacher’s car. It was a brand new Volkswagen Beetle and he wasn’t pleased.

“The headmaster bawled me out the next day in assembly. He called me the ‘carbaretta cowboy’ which stuck as my nickname.”

Bennion was able to afford the latest mod threads after starting on his five-year work-based training programme with the Wates Group aged 18.

“I learned about most areas of the construction industry through my training, from concrete fixing to architecture, engineering and building surveying, and used to study for four months each year at Croydon Technical College,” he says.

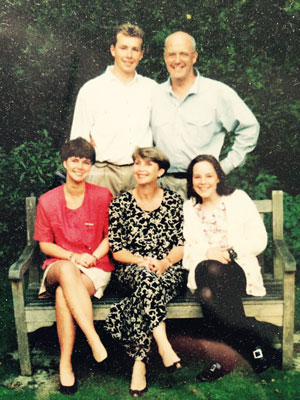

Bennion married Liz in 1968 and they had three children Zoe, now 44, Matthew, now 43, and Alice, now 38.

He had been promoted to the role of managing surveyor before leaving the Wates Group temporarily in 1983 to work in Singapore for a firm called Singapore Land.

“I was the clients’ contract adviser for a huge hotel and retail development on reclaimed land,” he says.

“I suppose that it was the making of me really, as working with 20 or 30 different nationalities out there made me a lot more outward looking.

“We took our children to Singapore too. I think going to school out there and mixing with different cultures set them up to be tolerant and broad-minded people too.”

Bennion returned to the Wates Group in 1986 as commercial director for London and became group commercial director in 1991, then group managing director a year later, and finally group chief operating officer in 2000.

“We always believed in training young talent at Wates. A successful business should be like a pyramid, with lots of young people at the bottom, then fewer, more experienced people as you get higher up,” he says.

“Moving on to the Construction Youth Trust after that was such a privilege.

“I feel very proud that together with my fellow trustees and the staff, we were able to change people’s lives for the better.

“It is a question of giving people a chance. The construction industry needs talented young people and this was a good way of helping.”

Bennion, who is still chairman of the board for bridge building firm Mabey Holdings and utilities construction specialists McNicholas Holdings, has no intention of winding down his activities for the foreseeable future.

He says: “I keep telling myself that I will stop it all in a couple of years’ time, but it never seems to happen.

“I love construction, the challenges it throws up and opportunities it gives so many people to succeed.”

————————————————————————————————————————————–

It’s a personal thing

What is your favourite book, and why?

It’s Birdsong by Sebastian Faulkes as it combines a great love story with the horrors and futility of war

What do you do to switch off from work?

I spend time with my family and enjoy gardening and sailing. A glass of wine also helps

What’s your pet hate?

Lack of respect for others

If you could invite anyone to a dinner party, living or dead, who would it be?

Nelson Mandela. I met him by accident once as he came into the Dorchester Hotel on a visit to London. I went up to him and shook him by the hand — can you imagine shaking the hand of your living hero? I have always admired him for his power of forgiveness and his belief in the suppressed talents of the South African people. I would also like Lord Nelson and Winston Churchill to be there. I’ve read a lot about Nelson and he was such an inspiring leader who always looked after his men. For all his human failings, Churchill was the greatest leader this nation ever produced

What did you want to be when you grew up?

A teacher. Some would say of course that I never have [grown up]

Your thoughts