Within moments of going into MP Barry Sheerman’s Westminster office, numerous clues hinting at his old day job as a university professor become clear.

Political biographies, volumes of poetry and literary criticism line the walls and by the time the interview is over, a small stack of books has built up in front of me to thumb through.

And as Sheerman leaps up to show me something else, so the conversation bounces just as energetically in different directions as I learn about the different projects he’s helped to set up.

“I unfortunately got into Parliament in 1979 when Thatcher became Prime Minister, so I had 18 years in opposition,” says the Labour politician, who counts co-chair of the Skills Commission with Dame Ruth Silver among his current roles.

“I did loads of shadow minister jobs and it was so frustrating that you weren’t doing anything — so I got in the habit of starting things and gradually built up this empire of social enterprises.”

Sheerman guesses he’s on his 48th enterprise having started with a co-operative development agency in West Glamorgan, followed by a folk club and a jazz club, “and it went from there”.

The enterprise he seems most proud of is an education centre run from the home of 19th century poet John Clare in Helpston, Cambridgeshire, which he discovered was on the market seven years ago.

“We got £1.27m from Heritage Lottery, match funded it, and turned it into a splendid centre, which is both a place where you can worship John Clare, but also it’s a national centre of learning outside the classroom,” he explains.

The project has expanded into the old village pub where Clare learned to play the fiddle.

“We are going to turn that into a hub where anyone can come in through the door — and they may be a young NEET [not in education, employment or training] who has lost their way, doesn’t know what their talents are, never been given any sound advice or maybe a 43-year-old woman who has never found that spark,” says Sheerman.

I wanted to change the world — so I got on the local council

“But they can come through and we use a businessman, managers, university academics, anyone who will give their time to assess them and mentor them and point them in the right direction.”

Middlesex-born Sheerman, aged 73, has long been an advocate of the FE sector (he’s a former chair of the House of Commons Education and Skills select committee, which has since focussed on education) and says his interest dates back to own experience of education and careers advice.

“I went to a grammar school, it was very posh, and most of the kids from the more working class background dropped out at 16, and I came top in English, top in history and bottom in everything else, so I dropped out,” he said.

A careers adviser told him to try and get into the chemical industry — “he said the future was men in white coats,” says Sheerman.

“So I ended up foolishly being in the paint industry and most of the time I got a day off to study chemistry and paint technology, most of the time with that day off, I went in and was reading economics — and I suddenly got this love of reading about economics.

“And a couple of nice people in the chemical industry said: ‘You should go back and get an education, you shouldn’t be here’.

“So I sold my scooter, I started a painting and decorating business, I cleaned windows, I bought and sold in Petticoat Lane, and I worked my way through my A-levels in a year at Kingston Technical College, and got a scholarship to the LSE to study politics and economics. So that was my liberation.”

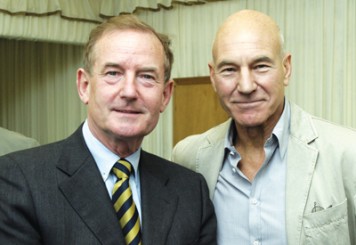

Sheerman married wife Pamela in 1965, and his best man was ex-Labour MP and former UKIP Euro MP Robert Kilroy-Silk (“I keep that quiet though,” says Sheerman with a chuckle).

Sheerman went on to do a Masters in political sociology, and was taught by Ralph Miliband, father of Labour leader Ed Miliband, before taking up a lectureship at the University of Wales in Swansea in 1966.

He taught economics and politics in Swansea for 12 years and clearly relished it, but tragedy turned his attention to “changing the world”.

“I was sitting there congratulating myself, as kid from a reasonably working class background, youngest of five, at being a university teacher, we had this lovely cottage on the Gower Peninsula with a couple of acres, toy farm breeding donkeys,” he says.

“It was a really self-congratulatory phase of my life, and then our first baby died at birth.

“In those days they took the baby, it disappeared — my wife was told the baby had been incinerated, I was told it was put in a mass grave.”

The baby, a boy who would have been named Luke, was born in November.

“Anyway, I did this strong partner act, I think, I tried to support my wife,” says Sheerman.

But by the New Year he realised he was struggling.

“I’d lost all my energy, I thought I had leukaemia, I kept getting a sore throat and losing my voice,” he says.

“My wife conned me into going to the university doctor, who gave me a total check-up and told me: ‘There’s nothing wrong with you physically, but men, as well as women, go through a period of reflection after they lose a child,’ — they didn’t say depression then.

“And that was the trigger, asking: ‘What do you really want to do with this life? Spend your life thinking you’re a little working class boy who has made it good… or is what I really want to do in my heart something more active?

“And out of that I decided I didn’t want to write about politics or teach about politics, I wanted to change the world — so I got on the local council.”

Sheerman ran unsuccessfully for a seat in Taunton in 1974, before being elected in Huddersfield in 1979.

He now lives just outside Huddersfield, and he and Pamela now have four children, Lucy, 43, Madlin, 41, John, 35, and Verity, 32.

As he enthuses to me about crowdfunding, an online system where individuals donate money to help get businesses and projects off the ground, I suspect there will be more social enterprises to come.

And his commitment to promoting FE remains unwavering.

“It gave me my second chance,” he says.

“And I only knew about it because people were kind enough to take time to say ‘Look…’ to me, and that’s really nice, when you see someone who is slightly off course.

“So I suppose what inspires me is when I look at kids who are like me.”

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

It’s a personal thing

What’s your favourite book?

I read Caitlin Moran’s How to be a Woman, and I just read Giles Coren’s How to Eat Out. My favourite book as a student was Rationalism in Politics and Other Essays by Michael Oakeshott

What’s your pet hate?

I can’t think of anything I hate. Hating is hard, isn’t it? I’m with Giles Coren. I hate people who go to restaurants and pay a lot of money for heated up beef. It’s such a waste of money

What did you want to be when you grew up?

I suppose on reflection I am a frustrated writer

Who, living or dead, would you invite to a dinner party?

John Clare [English poet who died in 1864] and Victorian slavery-abolition and factory reform campaigner Richard Oastler

What do you do to switch off from work?

Play with my grandchildren — I’ve got nine under 11. I love walking and reading poetry.

Your thoughts